Ministry of Flat Walks 03 : Tarn Hows

31 October 2017

To follow this walk, open another tab on your browser and go to this web address:

http://bit.ly/2zi5Iae.

John and I spent the last weekend but one, about ten days ago, at Cark. We were hoping to admire the autumn colours; but the high winds of recent weeks have already stripped the leaves from many of the trees, and there is much less colour to be seen than in more gentle autumns. There was also not much sunshine to bring out the colours which remained. We did, however, take the opportunity of a break in the rain and cloud to do one of our favourite and most familiar walks, around Tarn Hows. The trees were not at their best, and it was too cold to linger, but we made the most of it.

Some of my earliest memories of the Lake District are connected with Tarn Hows. Before 1964 our family spent at least two long weekends in small hotels in Hawkshead, and once for a whole week in a guest house close by. On one occasion we had two rooms, not adjacent but around a corner, with the courtyard below. Dad contrived to construct a miniature bucket line across the corner of the courtyard to connect the two rooms. (At the time I was fascinated by bucket lines, which you could see in the fields by the East Lancashire road where sand was being excavated for Pilkington’s glassworks in St Helens.) The hotel management was not impressed and made Dad take it down.

I know this all happened before 1964 because that was the year we had our last successful hotel holiday, at Glyndley Manor near Eastbourne. I was eleven years old and was allowed to miss two weeks of school, including the 11 Plus examination, from which I was excused as I had already won a scholarship to attend the Liverpool Institute high school. I can still remember quite a lot about that holiday: the miniature trams in a park near the sea front a Eastbourne; playing cricket in that park, one of the very rare occasions when Mum joined in; finding that Bexhill beach was better than Eastbourne, because Eastbourne has a lot of shingle, which Bexhill does not; driving out past Hastings to Rye and Dungeness, so David and I could travel on the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch narrow gauge railway. I even remember watching the television show Saints and Sinners in Glyndley Manor’s TV room.

The following year we went to stay in a hotel in Swanage, but had to come home early because I was unwell. That was when my asthma was becoming worse. Mum and Dad decided there would be no more hotels; instead they would buy a holiday cottage, which I suspect had been a long held dream but for which they now decided the time was right.

So I’m pretty sure that my early memories of Tarn Hows go back before 1964. At that time, though it has always been known as a beauty spot, it was less crowded or developed. You reach Tarn Hows along a narrow road up through the hills from the east. (The road going west is one-way, away from Tarn Hows.) At a crest on the road the vista over the tarn suddenly opens out, and there is a parking place which has in the last few years been designated for disabled drivers only. The road drops down to the west, never quite abutting the tarn but with a slope of grass and bracken down to the water’s edge. We used to park here and sit near the lake for our picnic while I ran around on the grass. Mum and Dad would sit or lie on the blue tartan rug which we still have today – an iconic possession. We probably also fed the ducks, many of whose descendants may still be seen on the water.

But in those days you could not walk around the lake unless you were prepared to force your way through the bracken on the hillsides and wade across the marshy bit at the head of the tarn. I have an idea that we tried once or twice but were always driven back.

Unexpectedly, Tarn Hows is not a natural feature at all. A nineteenth century landowner constructed a small dam across the gully where the stream runs down towards Yewdale Beck, thus causing three tiny tarns – they must have been little more than puddles – to merge into one. You almost have to walk down to the dam, in the south west corner of the tarn, to notice its presence. The site feels entirely natural and its reputation as a beauty spot is well deserved.

But over the years that reputation has spread, and when the weather is fine, or at almost any time during the holiday period, Tarn Hows is crowded with people. The National Trust now owns the land and over the years has made a number of improvements, including a car park tucked away in the trees to the south west, near the road which leads down to Coniston. They have made a good job of it: the car park is not an expanse of tarmac, but surfaced with loose stones and gravel, surrounded and interspersed by trees so it does not obtrude on the landscape. Nonetheless, at busy times the car park fills up and on two occasions recently John and I have had to turn away and go elsewhere for lack of a parking place. If you are planning to visit Tarn Hows you should go in the morning, the earlier the better.

The National Trust has also been responsible for constructing the well-made gravel path around the tarn which John and I followed a few days ago. It is not in fact all that flat. On the west side it rises and falls across the folds of the land, and on the east it rises slowly up to the road. But none of the slopes is very severe, and the stable footing afforded by the gravel makes it an easy walk. The path is broad and gentle enough for prams and, I imagine, wheelchairs so long as they have someone fit and strong who can push. I estimate the whole walk is about a mile and a half and takes about forty minutes, or longer if you take the chance, as you really should, to stop and admire the view. One of the advantages of the path, apart from the obvious, is that it has opened up entirely new viewpoints from which the tarn and the hills can be admired.

I believe the path must have been completed some time between 2001, when Mum and Dad sold their Lake District cottage at Woodgate, and 2011 when John and I bought Stable Mews. One of my last memories of being out with Mum is of walking around Tarn Hows on a path which had been opened but was still in some places no more than a muddy track. I remember that there was a precarious narrow footbridge at the head of the tarn; we had to be careful to keep our footing, or we would fall into the marshy brook. On that occasion, Mum and I were on our own. Dad was probably back at the car and John was not with us. So I think this may be a memory from 2001 when I was convalescent after my stroke.

At various places by the side of the path are fallen tree trunks, and a curious custom has grown up of pushing small coins into the bark, where they stick and, over time, gradually erode. People do the oddest things. I suppose it is a good-luck charm like tossing coins down a well, but if the National Trust took away the tree trunks, burned away the wood and melted down the coins they would have quite a valuable chunk of metal. This mass of coins does at any rate show how popular the walk has become.

If the short walk around the tarn is not enough for you, there are plenty of options to extend it. Once, on holiday with two Oxford friends some time during the 1970s, we parked our car in Coniston village, then walked up to Tarn Hows and back. We climbed the hill from Monk Coniston (see map), aiming for a path through the woods which the map assured us was there but which we could not find, then from Tarn Hows back down the gully to Yewdale and along farm tracks and the main road to Coniston. You can attempt this walk with much greater ease today, as the National Trust has constructed a gravelled path through the woods, and there is also now a well-made path down Yewdale to Coniston. But I don’t think it would qualify as a flat walk.

——————–

Dune

29 October 2017

Frank Herbert’s novel Dune was published in 1965. The following year it won the top two awards in science fiction publishing, the Hugo and Nebula awards, and was widely hailed as a classic of the genre. It has largely retained that status, and has been massively influential on science fiction and fantasy writing, ever since.

It is not, however, an easy read. I first became aware of Dune in the early 1970s, when I started to follow science fiction more closely. But it was only at my third attempt that I managed to read through to the end. Around this time I remember seeing a copy on Dad’s bedside table. He said it had been recommended to him (I don’t know by whom) but he had been unable to get very far into the book as it gave him nightmares. I can well believe it. Dad did suffer from nightmares from time to time, and some of the images from Dune would be unsettling for anyone.

The difficulty does not arise from Herbert’s style of writing, which is for the most part serviceable (we will come later to the one exception). But from the outset the story is told as if to someone who is already familiar with all the ideas and background that it introduces. Exposition is provided only where it arises naturally through the narrative, and often only briefly.

And this is a densely packed novel. Herbert’s imagined universe is more complex and multi-layered than in any other science fiction that had previously been published. It includes a galactic Empire with feuding great families, or Houses, each controlling one or more planets; multi-factional politics, with the Merchants Guild, the Pilots’ Guild and the Bene Gesserit (a shadowy pseudo-religious society of women) vying for power alongside the Emperor and the Houses; no artificial intelligences, which have been proscribed, but in their place Mentats, men whose minds function with great capacity and speed; a vividly imagined desert planet, the Dune of the title, with detailed attention to how people might live when water is scarce and conservation is essential to life; a rare “spice” which extends life, expands consciousness and is essential to space travel, but is deadly addictive, and is found only on Dune; and a desert people, the Fremen, who are Dune’s native inhabitants but remain largely secret from the Empire. None of this is decoration. Each element is important to the tightly-woven plot.

I recently read Dune again, for the first time in perhaps twenty years. (It is a good book for long journeys: you will surely reach your destination before you turn the last page.) As I did so, I was quite surprised by how much I remembered. It is still a good story. But I was also more aware of its weaknesses.

Herbert would not have claimed to be writing great literature, and his characters are for the most part ciphers who act according to their roles, not their personalities. That is, or at least was, par for the course in much genre fiction (actually I think modern standards are somewhat higher). More seriously, there is a disjunction between the two halves of the book; the turning-point comes where the protagonist, Paul Atreides, escapes into exile. Up to that point it reads like a hybrid of science fiction and political thriller in a well-imagined future society. From then onwards we see Paul adapting to life among the Fremen, rising to leadership and setting the seeds for future jihad, about which he feels guilt. There are lengthy passages about the effect of the spice on his consciousness which are poorly written and tedious; the main story is put on hold while we endure a lot of mystical twaddle. Only in the final chapters are all the strands pulled together to reach a fully satisfying conclusion.

There are other details which passed muster in 1965 but grate for a modern sensibility. Dune’s women are mostly adjuncts to their men; the women-only mystical/religious faction, the Bene Gesserit, is described in negative terms, and maligned by other characters as witches. And, in this age of militant Islam, it has become impossible to ignore the cultural appropriation involved in Herbert’s use of Middle Eastern models for his imagined desert people. Perhaps, in another fifty years, we will accept that Herbert’s writing is of its time, like Austen’s or Trollope’s. But, for now, these elements of Dune feel insensitive and crass.

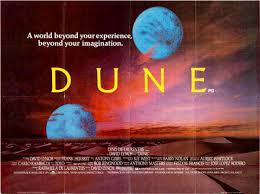

Not surprisingly Hollywood producers quickly spotted the cinematic potential of Dune. But it took at least two stalled attempts before a film version was completed, directed by David Lynch, executive produced by Dino de Laurentiis and produced by his daughter Raffaella. John had a DVD of the film (which I think had been distributed free with some journal or another) up at Cark, but I have brought it home to watch on my large-screen television.

The film was not even controversial when it was first released; almost everyone – critics and audiences alike – deemed it a stinker. A distinguished cast could not rescue it from disaster. It was said to be incomprehensible, ugly, poorly acted (or, more likely, directed), and lacking any emotional core. Some of those criticisms, alas, are true.

The film was not even controversial when it was first released; almost everyone – critics and audiences alike – deemed it a stinker. A distinguished cast could not rescue it from disaster. It was said to be incomprehensible, ugly, poorly acted (or, more likely, directed), and lacking any emotional core. Some of those criticisms, alas, are true.

Perhaps any attempt to reduce Herbert’s epic tale to two and a half hours on screen was doomed to failure. The film makes a valiant attempt to introduce and explain its densely-imagined world to audiences, but anyone who has not read the book will struggle to keep pace. And if you have read the book, while you may forgive the necessary omissions and simplifications, some of the grotesqueries introduced by Lynch seem light years away from Herbert’s original. His conception of Baron Harkonnen, the main antagonist in the story, is one example among many.

The visual style is an extraordinary mixture of steampunk, baroque glamour, and psychedelia. Lynch fares no better than Herbert in attempting to depict Paul’s expanded consciousness brought on by the spice drug: these episodes are simply dull, with imagery that is at once pretentious and obvious. The massive sand-worms whose life cycle is bound into the presence of spice are adequate on their own, but the scenes where they interact with people (I am trying to avoid spoilers here) are poor. Four years earlier George Lucas had produced his first Star Wars film in which the special effects are far superior. It is understandable that Lynch did not want his film to look anything like Star Wars, but he could still have learned from Lucas’s techniques.

Not all the acting is poor. Patrick Stewart puts in a characteristically dignified turn as Paul’s tutor and comrade-in-arms. Sian Phillips is effectively melodramatic as a Bene Gesserit witch-woman, bringing memories of her scene-stealing Livia in the BBC’s I Claudius. But I have never thought much of Lynch favourite Kyle MacLachlan, who plays Paul Atreides: every role he takes seems to turn out the same, an innocent learning disillusion. And Francesca Annis, who as Paul’s mother and fellow-exile should have the most interesting emotional arc in Dune, is extraordinarily wooden. As she is a fine actress – I still remember her with much admiration in Trevor Nunn’s production of Comedy of Errors for the RSC – this has to be down to the direction. Perhaps it was an attempt at dignity. But, if so, it fails.

Paul Atreides (Kyle MacLachlan) and his mother Jessica (Francesca Annis). Note the elaborate hair-do in the middle of a howling desert.

I saw the film on the large screen when it was first released. Some of the most striking images had stayed with me, though I also remembered, when I watched it again recently, how much it had botched the story.

What I also realised this time, and had missed before, is the implicit fascism in the scenes when Paul addresses the massed ranks of Fremen as they prepare to overthrow the Harkonnens. Another de Laurentiis movie, Conan the Barbarian, was accused of this, unfairly: Conan is a Nietszchean superman, but he has no aspirations to leadership, only to revenge. But in Dune the admiration for a fascistic religious fanaticism is unabashed. Herbert was more subtle: Paul foresees, and is troubled by, the risk that arousing the Fremen will lead to a religious jihad. In the film he has no doubts. It is not a philosophy I wish to admire.

I should like to see another attempt at rendering Dune on screen, perhaps as a television series in the manner of Game of Thrones. With an expanded canvas and modern special effects, the producers could introduce Herbert’s invented world more gradually and yet do full justice to its moral and political complexities. But without the fascism, please.

——————–

Grange

21 October 2017

When John and I bought our house, Stable Mews, in Cark in 2011 (six years ago! – is it that long already?), we had a checklist of qualities we wanted to find in our Lake District home. We wanted gas central heating – we had uncomfortable memories of the coal fires at our parents’ Woodgate cottage, which were characterful but left the house mostly cold, and we did not want to have to cope with deliveries of coal or oil. We wanted somewhere that was ready to move in, and would not be too high-maintenance; we remembered all the trouble Dad went through in order to make and keep Woodgate habitable for Mum, and did not want to commit ourselves to undergo anything so burdensome. And we wanted to be within comfortable driving range of north Manchester, where John lives.

Stable Mews fitted all these criteria. It was obvious that John really liked the place from our first visit; we offered and bought it very quickly. But what we didn’t realise was that it has a couple of other advantages not on our list.

The first is that the railway station is so close, I can easily travel between Cark and Oxted by train, so can come and go here on my own. None of the other places we saw would have been so convenient.

The second took time for us to realise. At first we did most of our shopping in Ulverston, where Mum and Dad used to go. There is a Booth’s supermarket there which we still use today. But the nearest town to us is in fact Grange-over-Sands. Mum and Dad never liked Grange, and during all the years at Woodgate rarely visited the town. They saw it as a kind of Lake District equivalent of Eastbourne, full of retired people and lacking in life. But we have found there is a lot more to the town than that.

It’s true that Grange is just a bit twee. There are an awful lot of tea shops (not coffee shops: all locally owned, no Starbucks or Costa), and several places which sell nick-nacks of no conceivable utility and precious little decorative value. But there is also no supermarket, and that has allowed local traders to flourish.

Grange Bakery is a local business which makes excellent bread, better than I can get anywhere in Oxted. Their fruit loaves are a breakfast favourite, though they have to be ordered in advance. The Bakery supplies general stores all around the district and it is rare for their products to be left on the shelves unwanted. Higginson’s butchers similarly far outperform anything in Oxted. Their meat is sourced locally – the saltmarsh lamb, only available at this time of year, is a particular highlight. They make their own hams which supply John for his evening sandwiches, and they produce a range of pies and quiches better than any supermarket.

I am particularly fond of Fletcher’s, a combined greengrocer and old-fashioned grocer. Inside the shop is the grocery section: not a full range of products, since they have no biscuits or canned food or tea and coffee, but what they have is high quality stuff. I love their English breakfast marmalade, which I buy regularly and take home with me to Oxted. They keep things like dried apricots in large jars and weigh them out into little paper bags for their customers. Despite the absence of sliced meats and biscuits in tins, this part of Fletcher’s reminds me a good deal of Amundsen’s, the grocer at Childwall Fiveways which Mum patronised for many years until Mr Amundsen retired.

The greengrocery is set out in market-stall fashion just outside the shop. The apples are not always very inspiring, and we have found that the tomatoes are bland. But the soft fruit, often brought down from Scotland, is usually very good, and they have an excellent range of vegetables, again locally sourced whenever possible. Almost nothing, apart from the soft fruit, is pre-bagged, so you can choose exactly what and how much you want. Fletcher’s business would suffer badly if Booth’s ever succeeded in opening a branch in Grange; I suppose it will happen eventually, but I really hope that day is far off into the future.

Grange is more than just a haven for foodies. On the main street, near the top of the hill, is a shop called Lancaster’s which is really quite hard to categorise, so wide a range of stuff does it offer. Lancaster’s has paint, tools, light bulbs, kitchenware, linens, camping gear and an excellent range of footwear for town and country. I suppose you might describe it as hardware and footwear, but that scarcely does justice to the range of goods. It is the kind of shop you like to wander around just to see what there is. And the staff, as in all the other shops I have mentioned, are helpful and friendly. When we were first setting up home at Stable Mews, we got quite a variety of bits and pieces from Lacaster’s: we did not need to look anywhere else.

I usually travel up to Cark on Thursdays and the following morning take the train back to Grange to do my shopping. If the trains keep to time (not guaranteed!) I have just fifty minutes to go the rounds, which is doable so long as I don’t dawdle. Grange’s railway station has retained many of the old features from Furness Railway days, including glass canopies and decorative ironwork on both platforms which have recently been restored and repainted. If my return train is delayed or cancelled, as has happened from time to time, the station is not an uncomfortable place to wait. The journalist Simon Jenkins has recently published a coffee-table book called Britain’s Best 100 Railway Stations, and I am pleased to see that Grange has an honoured place among them.

I have dim memories from my childhood of visiting Grange, possibly with Grandma and Grandpa, and walking along the promenade. The railway runs alongside and I can just barely recall standing on one of the footbridges while a train passed by. At high tide the sea used to rise across the mud flats of Morecambe Bay right up to the promenade, but that no longer happens: Some years ago the mud flats were colonised by tough cord-grass (spartina) which seems to have fixed them in place: at high tide the sea is now a quarter of a mile distant, and these are the salt flats which produce Higginson’s excellent lamb chops. There are however reports that the main channel of the River Kent has recently changed its course flowing into Morecambe Bay, which might bring the tidal waters back towards the town. That would be fun.

Near the station are the ornamental gardens, proudly maintained by the town council, in which there is a large duck pond. Some excitement was caused locally when new rare ducks, specially imported for the pond, disappeared – presumed stolen – soon after they arrived. I’m not quite sure why everyone was so certain that the ducks didn’t simply fly off. Do they have their wings clipped? The pond does have at least one other resident, a large proud Muscovy duck called Boris, who apparently arrived and has stayed of his own volition. I guess you win some, you lose some. Even with ducks.

——————–

Dido, Queen of Carthage

20 October 2017

A couple of years ago, in a rare production at Stratford of Christopher Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta, there was a rather good visual joke. The stage hands, who normally wear sweatshirts blazoned with the Royal Shakespeare Company’s iconic RSC logo, had had some new shirts printed as if for the RMC – that is, the Royal Marlowe Company. Ever since then, John has wanted an RMC sweatshirt of his own; but, alas, they do not seem to be on sale.

A couple of years ago, in a rare production at Stratford of Christopher Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta, there was a rather good visual joke. The stage hands, who normally wear sweatshirts blazoned with the Royal Shakespeare Company’s iconic RSC logo, had had some new shirts printed as if for the RMC – that is, the Royal Marlowe Company. Ever since then, John has wanted an RMC sweatshirt of his own; but, alas, they do not seem to be on sale.

Behind the joke is a worthy observation. Marlowe died at the age of 29, by which time he had already produced a handful of plays, most famously Doctor Faustus which is fairly regularly revived. His work was enormously successful in his time, and a clear influence on Shakespeare. If he had lived, the RMC would not be such a fanciful idea.

John and I have just (last weekend) been to see another Marlowe production at Stratford: Dido, Queen of Carthage, which is believed to have been his first play. We had seen it before, in a rather undistinguished production at the Globe theatre; but I had no clear memory of it.

We will remember this production much better. It had among other things two fine central performances, from Chipo Chung as Dido and Sandy Grierson as Aeneas, and a succession of memorable scenes and images conjured up by director Kimberley Sykes. As with the best of the RSC’s revivals of forgotten plays, it made us wonder why productions are not more common.

The play dramatises an episode from Virgil’s great epic poem in Latin, the Aeneid. Writers of Marlowe’s time regularly used stories and themes from classical sources, but what is less usual is how prominent a role Marlowe gives here to several of the Olympian gods: Jupiter, his wife Juno, his messenger Mercury, Venus and her helper Cupid. It is largely through their intervention that tragedy occurs. Aeneas is a son of Venus and a survivor from Troy. When Juno causes him to be shipwrecked on the shore of Africa, Venus guides him to the court of Dido and causes her to fall in love with him. But Jupiter decrees that Aeneas must proceed to Italy to fulfil his destiny as an ultimate founding father of Rome. Dido, deserted, kills herself.

Marlowe was widely suspected of being an atheist: a dangerous suspicion. But by appropriating a story from the classics he neatly sidestepped any risk of being charged with blasphemy. Everyone knew that the Olympian gods were capricious, quarrelsome and vindictive; it was much better to avoid their notice. (I often wonder what the Greeks and Romans, who were nobody’s fools, really believed. Surely not these tales like something from a raunchy soap opera. But that’s another story.)

Perhaps, however, this is part of the reason why Dido is now rarely performed. Where the protagonists of Macbeth and Othello and even Doctor Faustus are undone by their own tragic flaws, here Dido is pierced by Cupid’s arrow to fall in love with Aeneas, and he is compelled by Jupiter to desert her. Neither of them makes any meaningful choice, and that makes them less interesting characters.

But the play is still full of good things. I think we first realised we were in for something special during the long scene when Dido first receives Aeneas at her court. She has heard rumours of the fall of Troy; now she wants the truth, in detail, from a survivor. Aeneas is reluctant but eventually tells the story and its scenes of mounting horror. Twice he falters and has to be urged by Dido (in dialogue which is remarkably true to life) to continue and complete his tale.

I suppose this must be Marlowe’s first great speech, and Sandy Grierson does it full justice. You can feel his resentment and anger building up and bursting out as he recalls the story of the Greeks’ deceit and their brutality. In modern terms, he has a classic case of survivor’s guilt – a syndrome which Marlowe clearly recognised. Grierson not only speaks the verse clearly, with sincerity and nuance, but acts it too. At the climax of his narrative Dido, her courtiers, and the entire theatre are driven into silence.

The worst thing you can say about Aeneas / Grierson is that he maintains this tone pretty much for the entire play. In one of the online blogs someone said that he is a bit of a whinger. But to me that seems a bit unfair. He has been told he has a certain destiny, but the gods seem very reluctant to allow him to set about fulfilling it: quite enough, I’d say, to foster a feeling of resentment. When he seeks a compromise – he will establish his new Troy, but here in Africa with Dido, not in Italy – Jupiter sends Mercury to enforce the original plan. Dido is collateral damage. Perhaps the character is a bit two dimensional; character was not Marlowe’s strongest point. But those two dimensions are vividly realised.

For the first half of the play, Chipo Chung’s role as Dido is subordinate to Aeneas, but in the second half she comes into her own. At first she is capricious, then pleading, then defiant. Chung makes the most of Marlowe’s vigorous, rhetorical verse. You really believe in this powerful woman, stung by Cupid’s arrow yet fighting to retain something of her dignity. The role should be an actor’s dream, yet also a nightmare: it could so easily be overplayed and become ridiculous. Chung avoids this trap, making Marlowe’s verse seem right and true. The same blogger commented that he couldn’t understand what Dido sees in Aeneas, but this again misses the point. Dido has made no free choice; she is compelled into love by Cupid’s arrows, and to begin with, at least, you see her fighting against the compulsion. But to no avail.

Some of the credit for these performances must belong to director Kimberley Sykes, another whose name I did not recognise. According to the programme she has been assistant director on a number of RSC shows, but this is her first time in the lead. I shall be pleased if she now gets more opportunities.

It is startling how much the RSC’s directors are able to conjure up, on the apron stages of the main and Swan theatres in Stratford, with a minimum of sets and props. For all the excellence of Grierson and Chung, I think the image from this show I shall remember the most clearly is that of Juno (Bridgitta Roy) and Venus (Ellie Beaven), normally at daggers drawn, dancing wildly together to invoke the storm which traps Dido and Aeneas together in a cave, where they consummate their love. The Olympian gods were by no means all-powerful, or all-knowing, but they had power over weather, and here we were seeing it realised, as the water poured down from above the rear of the apron stage. I hope the producers remembered to install effective drainage along with the shower taps.

All the performances were very good, possibly excepting the boy actor in the role of Ascanius who was as wooden as usual – the RSC, for all its other excellences, seems to find it difficult to coach its child actors to play Shakespearean roles with the same naturalness as the rest of the cast. I particularly liked Ellie Beaven’s imperious Venus, Nicholas Day’s lustful Jupiter and Lucy Phelps in the small role of Cleanthus, one of Aeneas’ comrades – a male role given to a female actor, as the RSC seems increasingly willing to do. But it is invidious to pick out individuals from a fine ensemble. Fundamentally this is a play with two starring roles, and in this production Chung and Grierson do them full justice.

——————–

Thoughts on the train

19 October 2017

I came up to Cark on the train today. Nothing special about the journey, except for rather a long wait at Lancaster, about which more later. But there were several small incidents and encounters worth writing about. Perhaps, too, the uniformly grey, damp weather prompts introspection.

The journey started from Oxted station at about a quarter to ten. There was a queue at the booking office, so I used one of the automatic ticket machines, and then remembered what the booking clerk, Andy, told me a couple of weeks ago: someone in the office ordered the wrong blank ticket stock for the machines, of a type which doesn’t have the magnetic strip that is read by the automatic ticket gates. So at Oxted and Victoria, and on the Underground, I had to use the manned ticket gates in order to pass the barriers.

The gate staff were as incurious as always: they barely glanced at my ticket, and none of them asked to see the railcard which entitles me to discounted fares. I don’t suppose theirs is the most thrilling job in the world, though I can think of many worse, but it is a shame that they seem to take so little care over their work. In fairness, I should add that I had cause to be very grateful to the Victoria platform staff in 2001 when I had a stroke on the train in to London and collapsed on the platform. They took care of me, called the ambulance and stayed with me until it arrived.

I suspect it is the deadening routine which dulls their application to their duty, that and no sense of loyalty to a remote corporate employer whose every action seems to put profit ahead of people. The train operator Southern is engaged in long-running low-level industrial disputes with its guards/conductors (in connection with driver-only trains) and its station staff (job cuts). Everyone in the industry and outside it believes that the Government, which awards and funds train franchises, is prosecuting these disputes from behind the scenes. I more specifically see the dead hand of the Treasury, desperate for savings in the railways budget at whatever cost in effectiveness and service.

Travelling across London on the Victoria line, the train was as full as usual and I initially had to stand. A nice young lady offered me her seat, but I declined. This happens to me more and more often; it’s a bit depressing, and I rarely take advantage unless I am tired and/or wheezy. I have been wondering what it is in my appearance that causes random fellow-passengers to make these generous offers, since I don’t think I look noticeably older now than, say, ten years ago, when my hair was already greying. I suspect that it may be my flat cap which makes me look old. I started wearing my cap when my hair all fell out, and though the hair has come back I have kept the cap.

In any event the train partly emptied at Green Park. I found a seat of my own and almost immediately noticed, in two seats opposite, a middle aged woman with a little girl of five or six years old. They were both carrying rucksack-type bags, enough for a day’s outing or a couple of days away at most. The girl was quiet and clingy. The woman was showing signs of intense grief – dry-eyed, but with the deepest frown imaginable, her arms wrapped defensively together and her hand frequently up in front of her face. I would guess that she was barely holding herself together for the sake of the child.

I’m not sure anyone else had noticed. People famously keep themselves to themselves on the Underground. But what should you do when you see something like this? For the next five minutes, until the train reached Euston, I was on the edge of leaning across and asking if there was anything I could do to help. But I didn’t: classic English reserve, and perhaps a tinge of fear, won out over sympathy. Perhaps, if they too had got off the train at Euston, I would have said something. But they didn’t, and now I am feeling a twinge of guilt over my inaction.

The journey north to Lancaster was largely uneventful. I did not have a reserved seat, but the train was not too full, and in any event Virgin (the operator) keeps two standard-class carriages free of reservations on every 11-coach Pendolino train. Until recently these were two adjacent coaches, F and U (for Unreserved – in the middle of the train) but for some reason Virgin has changed that, so the unreserved carriages are now C and U. This seems arbitrary and a bit silly, when the previous policy was quite sensible. I wonder why it has been done.

The timetable is so arranged that three or four trains pass northwards through Lancaster towards Scotland within a space of about 25 minutes, repeated every hour. The fast train from Euston, on which I travel, is always the first of these, so there is a half-hour wait for the local service to Barrow, which connects with all four. Today, however, it was worse. The incoming local train was running late and when it arrived I saw why. It was a Pacer.

For those not in the know, let me explain. Pacers are diesel trains, two coaches long, which were introduced as a cheap expedient when the railway was in the doldrums in the 1980s. Their bodywork is essentially the same as two single deck buses and they have only four wheels per carriage, unlike all other modern trains (and most trams too) which have bogies. They are flimsy, underpowered and give their passengers a horrible, bouncy ride. Pacers should have been scrapped years ago, but somehow have survived past their designed lifespan.

This one had evidently had trouble on the inward journey. (I realised afterwards that it had probably been suffering from wheel slip on fallen leaves; a familiar railway problem with which the lightweight Pacers do not cope at all well.) I did not fancy it at all, and meanwhile the carriages for the next scheduled Barrow train, due to depart nominally an hour but in fact only half an hour later, were already waiting in an adjacent platform. So I let the Pacer leave without me, and caught the later train.

I took a table seat on this next train (I have never understood why anyone should prefer the airline-style seats, with the back of the next seat only a few inches from your nose) and was presently joined by a disgruntled middle-aged man who sat down opposite me. I could tell he was disgruntled from the conversation he immediately started on his mobile phone. His connecting train to Preston had been cancelled and ticket staff had told him he had to go back to Carnforth to catch a train to Shipley; having missed his connection at Preston, he was not allowed to travel via Manchester.

Leaving aside the Manchester prohibition, which might have been a stipulation on his ticket, this was such a mish-mash of bad advice I very nearly said so. I won’t go into all the reasons; that would be tedious. But, not for the first time, listening to one person’s end of a mobile phone conversation gave an alarming insight into how uninformed people can be, and how poorly advised. Was this another occasion to intervene? I did not feel quite able to do so, and I am not sure it would have helped him much if I had spoken. But nagging at the back of my mind is the thought that knowledge is not worth much if, when the moment comes, you fail to put it to use.