Michael Gilbert

29 May 2017

For the first couple of years that I lived in London, I had very little money. (After I earned my first promotion at the Department, things were not quite so tight.) I was living in a large bedsitting room on the Archway side of Highgate hill, and travelled to and from work every day on the number 134 bus. Any spare money that I had – and a bit more besides; I ended up with a sizeable unauthorised overdraft, which the bank manager at Lloyds in Liverpool kindly permitted me; I have banked with Lloyds ever since – any spare money was spent on the cheapest available concert and theatre tickets.

So there was very little to spend on books and LPs or other home entertainment. Instead I made extensive use of the Highgate public library. Quite often I would borrow, and finish, half a dozen books in a week. The time I spent on buses, and between the end of the working day and the start of whatever show or concert I was attending, had to be filled somehow. So in two years I worked my way through a lot of books. For some arbitrary reason which I cannot now remember I confined myself to authors with names in the first half of the alphabet, so I read a lot more A-Ms than N-Zs. I actually kept a card index of books and authors, but at least I didn’t descend to making little marks inside the front cover of books, as the most obsessive readers are said to do. Anyway, the card index disappeared long ago, so I now only have hazy, partial memories of all that I read.

But one that I do remember reading for the first time was Michael Gilbert. I must have picked him out more or less at random, but after reading one I was hooked, and gradually worked my way through whatever was on the library shelves. Then I forgot about him.

Gilbert seems to have been that kind of author; easy to read, easily forgotten. But that does not do him justice, not by a long chalk. He had a long writing career, from 1947 to 1998, so when I first read his books he was in his heyday. He wrote a mixture of whodunits, police novels, adventure stories, spy stories and thrillers – categories which sometimes overlap but, all together, cover quite a wide range. His versatility may have contributed to his current obscurity, since unlike Christie or Sayers he did not write long series with recurring characters which make life easy for publishers (and lazy readers). A couple of his policemen, Hazlerigg and Petrella, do appear in several books each, but at long intervals and not always as major figures. Many other characters appear in more than one book but rarely in more than two or three.

It is this versatility which, to my mind, helps lift Gilbert above the ordinary run of genre writers. You never quite know what you are going to get from him, except that it will be a well-crafted story, expertly told. It wouldn’t be quite true that he never repeats himself. His first published novel, Close Quarters, was a whodunit set in a cathedral close in the fictional city of Melchester, a setting repeated in his much later The Black Seraphim. He shows a fondness for Italy, which is the backdrop for several books including one of his best, The Long Journey Home. He clearly also has a sympathy for boys’ preparatory schools (perhaps he had fond memories?) which feature in several books, though they are central in only one, The Night of the Twelfth, which is a very Gilbertian mixture of whodunit, procedural and thriller. But these repetitions are incidental.

It is also true that, like many other thriller writers then and now, he has a fondness for the innocent hero caught up in events he doesn’t understand. But even these are quite cleverly differentiated. The protagonist of The Long Journey Home, John Benedict, is not looking for trouble, but resourceful and ruthless when he encounters it. The young pathologist James Scotland in The Black Seraphim is innocent and a trifle idealistic, which causes him a good deal of trouble. The polymathic Henry Bohun in Smallbone Deceased is knowledgeable and curious, and contributes as much as Hazlerigg to solving the crime. And so on.

In some of his later books Gilbert does away with the single-viewpoint protagonist altogether; a dangerous ploy, as there is no central character with whom the reader may identify, but in these expert hands it works well. Trouble is a thriller in which separate strands of racial tension in south London and an IRA threat gradually interweave to an explosive finale; The Queen vs Karl Mullen is a notably cynical story of intrigue in which leftist plotters seek to entangle and discredit an unsympathetic South African policeman. For a writer whose prevailing tone is comfortable and reassuring, a sour (and quite modern) streak of cynicism occasionally surfaces, and sympathetic characters are not always safe: in The Long Journey Home, another of his best, two characters, who in other hands we might have expected to survive through to the end of the book, separately meet sticky ends. On the other hand, the leading character (not the narrator) in The Heat and the Dust is a notably amoral businessman whose progress the reader follows with a mixture of admiration and horror.

In professional life Gilbert was a practising, indeed distinguished, solicitor. He wrote his books in longhand while commuting between his London office and his home in Kent, a feat which frankly amazes me; I guess he must have travelled first class. His professional background enabled him to write convincing courtroom scenes, but even in these he is careful not to repeat himself: a bankruptcy court in The Doors Open, a coroner’s court in The Black Seraphim, a libel action in The Heat and the Dust, even a planning enquiry in The Crack in the Teapot. There are no Perry Mason-style histrionics, but there is no shortage of drama either.

I have managed to collect about fifteen of Gilbert’s thirty novels, and one book of short stories, in second-hand paperbacks, all purchased online. They do not seem to have a modern publisher, which is a pity as I am sure he would find a market. The books I have obtained come from a variety of different publishers, and I wonder whether he was one of those authors who, for whatever reason, find it difficult to stay with a single publisher, which would certainly not have helped him to remain in print.

Of all his books, the one which I like the best is The Crack in the Teapot, in which a young solicitor in a (fictitious) seaside town is instrumental in uncovering corruption at the local council. The book has several Gilbertian fingerprints including the innocent protagonist who is for the most part quite unheroic, a prep school, a courtroom scene (the planning enquiry mentioned earlier), some deftly sketched-in and well differentiated characters and a swift denouement. It is also not obviously a novel of any particular genre, not a detective or police story, nor a thriller; I suppose “mystery” might just about fit as a label, but I think the best term is a story of intrigue, or more simply just a story.

If I had to sum up Gilbert in a single word it would be that he is a storyteller, and this may be why his books are still readable today. Only in the police procedurals, mostly those featuring Petrella, may you feel that time has passed him by: modern procedural novels are much more gritty and downbeat. Otherwise, the settings of the stories may feel a trifle dated, but the central plot threads remain vital and the outcomes satisfying. Gilbert is not a difficult read, but he is an enjoyable one.

——————–

Beamish

29 May 2017

John and I drove 120 miles yesterday (well, John drove; I read the map) to Beamish in County Durham, where there is an open air museum. It had taken a little persuasion to convince him that this long return trip would be worthwhile, but by the time we returned to Cark he was full of enthusiasm.

I first heard about Beamish many years ago from a colleague at work, Gavin Watson, who told me about this museum in the north east where they were installing lots of old industrial gear and restoring it to working order. But at the time I did nothing to follow it up. However, after John and I bought the house in Cark I started to collect tourist leaflets wherever we went – we now have a collection of them in two piles, a total of more than four inches thick, bound together with rubber bands and kept in a drawer in the dining room – and one which I picked up was for the Beamish museum. There was also an article in one of John’s railway magazines which piqued our interest. After that it was easy to find further details on the web (www.beamish.org.uk) and to work out that the museum was just within reach of a day trip.

Beamish is not the first open air museum I have seen. I visited the Ulster Folk Museum near Belfast in 1970 while staying with a pen friend, and the Ballenberg Museum in Switzerland during the 1980s while on walking holidays. There are also two good open air museums quite close to me in Oxted: the Weald and Downland Living Museum at Singleton in West Sussex, north of Chichester, where they have a good collection of old agricultural dwellings from the area, and the Amberley Museum and Heritage Centre north of Arundel, also in West Sussex, which clearly hopes to be something like Beamish one day but has about 30 years’ leeway to make up.

Beamish trumps them all. It is located on a large country site not far from Chester-le-Street, roughly rectangular in shape and about half a square mile in size. Within the museum there are several distinct areas depicting scenes of life in the North East at different times over the last two centuries: a country farm and waggonway from the 1820s; a colliery and pit village from the 1900s; a town street and park, also from the 1900s; a 1940s farm (which John and I did not visit); and a recreation of the railway station at Rowley, a few miles from Beamish, which was built in the 1860s and never modernised. In each case, many of the buildings and other installations have been dismantled at their original locations and re-erected, brick by brick, on the museum site. Others have been freshly built using designs, plans and materials typical of their period.

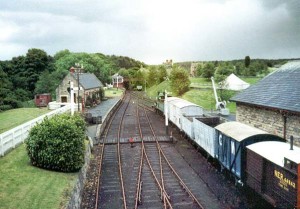

A tram line runs all around the site, with a regular service using vintage tramcars to help visitors move around from one area to the next – or simply for the fun of the tram ride. There are several other vehicles also in use or on display, including two old double deck buses (one of which seemed to be exactly the same make as those which I used in Liverpool in the 1960s) and a steam-powered traction engine. Two railway engines were in steam, one at Rowley station and one on the waggonway, which naturally received a good deal of our attention. There-and-back rides were on offer for visitors, but in each case the line was too short (the waggonway is barely 200 yards, the railway perhaps 600) for this to seem worthwhile. It was more interesting to watch from the sidelines. Unfortunately the colliery railway was not in service and, according to the guidebook, is likely to be rebuilt soon in any case.

The museum offered plenty of places to obtain food and drink (though John and I had brought our own picnic) and well-signed public lavatories, for which I was grateful. The staff whom we saw were dressed in appropriate period costume, and John was worried, I think, that they would turn out to be actors playing roles who would engage the visitors in conversation – he has a horror of audience participation. But fortunately that turned out not to be the case.

And in the park was a bandstand where a brass band gave a performance. I don’t believe that is a daily event, but this was Whit Sunday, probably the museum’s busiest day of the year to date, and all the stops were being pulled out. Bandstands always put me in mind of the one in Sefton Park in Liverpool, where I was once photographed, as a 4 or 5 year old, listening to and waving my arms around as if “conducting” the band. I still quite like brass band music, but it is a bit samey after a while, so we didn’t hang around to listen. In any event they were clearly audible from a good way off as we walked around the museum.

Beamish is far too large and full of interest to see everything on offer in a single day, so we focused on the big industrial installations – the trams, the railway, the waggonway, the colliery where there is a working steam-driven winding engine (though no longer anything for it to wind). We didn’t venture into the drift mine, for which there are half-hourly guided tours; by the time we reached the colliery village, we had been on site for more than four hours and we were both quite tired.

The trams were great. Only four were in service (Beamish apparently owns about ten that are in working order) but we had the good luck to catch the open-top tram (pictured above), which was fun in itself and also gave a great view over the whole site. We went three-quarters of the way round before getting off.

I thought the railway was a bit disappointing and I suspect that John did too. The station building was impeccably preserved, as was the one working engine (Bon Accord, an ex-Aberdeen Gas Works locomotive which appears to have its own preservation society), but the operations were rather desultory. I did like the signalbox, though, with its hefty metal levers painted various colours to denote their different functions; it reminded me of the one at Banks, mentioned in my blog on 18 April.

On the waggonway was the one absolute stand-out exhibit, a working replica of an early steam locomotive, the Steam Elephant. John will no doubt post photographs of the locomotive on his own blog, and I won’t steal his thunder. But a bit of research tell me that the Steam Elephant was originally built as early as 1815 for use on the wooden-tracked Wallsend Waggonway (www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/river-tyne-200-year-old-5325105) which makes it one of the very earliest self-propelled steam locomotives. I confess this was a bit of railway history that had completely escaped me.

In the waggonway shed were two more replica locomotives, including one of Stephenson’s famous Locomotion No.1. One of the nicest things about the whole museum was how much of it was open to the public: so far as I could see, only working areas were barred. Apart from the waggonway locomotives, we saw some of the other trams and a steam roller (yes, powered by steam) in their respective sheds. There were very few interpretive panels of the kind to be found in most museums: you are left to wander around and see as near as possible a recreation of objects, large and small, in their original environment. For more information there is a guidebook, and more is available on line, which I have used for this blog.

On reflection, perhaps we should have investigated more of the period buildings, especially the miners’ cottages in the colliery village, the 1820s country farm and the terrace of middle-class houses from the 1900s. But no doubt we will be back. It’s clear that Beamish doesn’t intend to rest on its laurels, so if we return in a couple of years’ time there will be more to see.

——————–

Les Misérables

22 May 2017

Georgina and I share a birthday, 18th May, though Georgina is a number of years younger than I am. This year we decided that for a joint celebration we would go to see the musical Les Misérables, currently running at the Queen’s Theatre in London. Georgina had seen the stage show some years ago. I had not, but we went together to see the film version, with Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe, when it was on in Oxted last year, and I subsequently bought the DVD so I could watch it again.

We went to see the show last Saturday afternoon, and had a pretty good time. Our seats in the Dress Circle allowed us a good view, which was further assisted by the three seats in front of us remaining empty for the whole performance. That was very lucky, as the staging is spectacular and we were able to appreciate it properly without having to crane our necks, as sometimes happens in less well-appointed theatres.

Les Misérables has been running in London for 32 years. It started life in the Barbican Theatre, a joint production by the Royal Shakespeare Company and a commercial promoter. The initial reviews were poor; but audiences were enthralled. The show subsequently moved, first to the Palace Theatre, one of London’s largest, and more recently to the Queen’s. Heaven knows how many different casts have played in it. You might think that by now attendance might be tailing off a bit, but on Saturday the theatre appeared to be full to capacity (apart from those three mysteriously vacant seats) and the audience gave the show a rapturous reception. Until musical tastes change, or there is an outbreak of war or civil unrest, there seems no reason why it should ever end.

When a production has been running for so long, it can become tired and stale. Changes of cast provide a brief infusion of energy, but not enough to make up the difference. By all accounts this happened long ago to the longest-running of all West End shows, The Mousetrap. Perhaps, one day, Les Misérables will suffer the same fate; but there was no sign of it on Saturday.

On the contrary, the whole thing ran like a well-oiled machine – and that is not just a simile. The stage machinery, and the crew who operate it, were really put through their paces. I don’t think I have seen any other show in which the revolve was put to such intensive use. Other tricks of stagecraft, including a trapdoor, a gauze and smoke effects, were all employed; and I particularly admired the lighting, especially in a scene when the protagonist Valjean makes his escape along the Paris sewers, represented simply but effectively by moving across a darkened stage from one patch of spot lighting to the next.

Just the same, I found the show – how to put this? – not quite as overwhelming as I had hoped. Perhaps the main reason was that the film is so very good, and though I didn’t set out to make comparisons (and haven’t watched the film for several months) I think my expectations may have been raised unfeasibly high. In a way, the opening sequence sets the tone. Valjean is a prisoner working in a chain gang, and on film you see exactly what he is doing: with his gang, he is hauling a large ship, inch by inch, up the slipway in a dry dock. It is a stupendous opening which conveys at once the brutality of his punishment and the cruelty of the officers. On stage this scene can only be suggested, and despite the harshly stirring music it simply does not have the same power.

The next scene is no less important, as it marks the turning point in Valjean’s life. He is on parole, but his papers mark him out as an ex-convict and no-one will give him work. He is offered food and shelter by the Bishop of Digne, but he is bitter and unreformed, and in the night makes off with the Bishop’s silverware. The police quickly catch up with him, but rather than turn him in, the Bishop lies, saying to the police that the silver was a gift. He then tells Valjean that he must use the silver “to become an honest man” and that he has “bought (Valjean’s) soul for God.”

On stage this scene is suggested by a handful of props, and is over and done with in a couple of minutes. Anyone who doesn’t know the story can easily miss its significance for everything that follows. The film treats it at greater length and gives it a proper weight.

These differences between stage and film are nothing to do with length. The film is 158 minutes long and the stage show almost exactly the same. But the film makes better use of the time. On stage, when the characters have solo songs (of which there are several), the action stops as they move to front of stage and address the audience. On film, the action doesn’t stop and the story can be carried forward by the visuals.

Almost every comparison of this kind works in the film’s favour. Another instance: for the film a 70-piece orchestra was employed, allowing great variety in colour and a far wider range of dynamics. For the stage show there was an orchestra of 14 and essentially they played either loud or soft. I had not previously noticed the limitations of Claude-Michel Schönberg’s music, but I now think they were obscured by the film’s sophisticated orchestral arrangement; with 14 players and a simpler musical score, they were more apparent. It’s true that there are some show-stopping numbers, which the audience much enjoyed, but by the end of three hours I was aware of a lack of variety in structure and harmony.

It is perhaps in the music, or rather in the singing, that the show most shows its age. When Les Misérables was first produced in London, there was an A-list cast led by Roger Allam, Michael Ball, Colm Wilkinson and Patti LuPone. But it’s pretty hard to get an A-list cast to lead even such a successful show when it is in its 32nd year. I should perhaps make an exception for Simon Gleason as Valjean, who was excellent throughout. But while the other lead singers on Saturday were all able to belt out their numbers, hitting and holding their top notes, they were less secure in the quieter moments, and projected less well.

The film is notorious for Russell Crowe’s “singing” (he plays Valjean’s relentless pursuer, Javert), but it never seemed to me a drawback: his harsh croaking rather suited the character. The producers clearly chose to cast actors who suited the parts, rather than for their singing voices, and I am sure that was a good decision. On film there is, of course, more need for acting, since the stage show functions in full opera/musical mode and any acting is secondary to the music and spectacle.

None of this mattered in the slightest to Saturday’s audience, who allowed themselves to be carried away by the show. Whatever my reservations about some elements, it is ultimately the overall experience that counts, and on stage Les Misérables is quite an experience. The story is a proper epic, recounting how one man earns a personal redemption against a wider background of oppression, poverty and revolution, and it is easy to see how this story, depicted in vivid primary colours of music and staging, has wowed two generations of audiences. Victor Hugo’s original novel was damned by contemporary critics, who disliked its vulgar subject matter, sentimentality and crude characterisation, but seem to have missed its overall sweep and passion. I do not want to fall into the same trap. Les Misérables is a fine show which has deserved its success. But I think that it is even better on film.

——————–

Fortepiano

21 May 2017

A fortepiano is an early piano. The fortepiano was invented around 1700, and the word can be used to designate any piano dating from then up to the early 19th century. Most typically, however, it is used to refer to the late-18th century instruments for which Haydn and Mozart (among others) wrote their piano music. During the 19th century the piano was gradually developed until, by the end of the century, it had evolved into something like the modern concert grand.

For most of the 20th century, the fortepiano was considered obsolete. But during the last couple of decades, interest has grown in the use of instruments which are as close as possible in design to those available in a composer’s own lifetime. Performance on these instruments is sometimes claimed to be “authentic” and thus more true to the composer’s original intentions.

I have my doubts about this, and would not generally go out of my way to attend a period performance of any kind. I am quite happy for musical scholars to learn what lessons they can from the use of period instruments, and for those lessons to feed back into modern performance styles, but beyond that the fashion for period instruments has always seemed to me to have a bit of the hair shirt about it. When the modern equivalents are so good, why deny yourself their benefits?

So I was slightly in two minds when Michelle invited me to attend a fortepiano concert in Kingston, to be given by John Irving, who is a professor of period performance at what used to be the Trinity College of Music (following a recent merger it has changed its name, but Trinity is what I recognised). However, I decided that I should expose my prejudice to the reality, and this, therefore, is how I spent the evening of my birthday last week.

I went to the trouble of looking up fortepiano in various reference sources beforehand. There is no standard design. However, the main feature is that, as in a modern piano, the strings are struck with leather-tipped wooden hammers (in a modern piano they are usually tipped with felt), rather than plucked with quills as in a harpsichord. This was a crucial design change because it should allow the performer, by varying the force with which he or she strikes the keys, to obtain a louder or quieter note. You cannot do this on a harpsichord.

A McNulty reproduction fortepiano very similar to the one we heard. Note the lightweight construction and the lack of pedals.

Michelle and I were able to obtain seats at the front from where we could watch the fortepiano in action. We were also able, during the interval, to have a good look at the instrument, a modern reproduction of an 18th century design, broadly shaped like a grand piano but smaller and lighter in construction. Apparently most fortepianos were built with no metal in their frame, and this seemed to be the case here. We could not see the hammer mechanism, but what I immediately noticed was that the strings were far thinner than in a modern piano. They also appeared to be of a uniform thickness, so differences in pitch were obtained entirely from the length of the strings. This may have been an optical illusion, but any differences in thickness were certainly very small compared to the strings in my own piano.

But what of the sound?

Irving gave the fortepiano every opportunity to shine. He played two sonatas each by Haydn and Mozart, who almost certainly composed for an instrument very like this one; plus two shorter works by J S Bach, who certainly did not. There was nothing wrong wih his performance, which I enjoyed, or with the music itself. But at the end of the concert Michelle and I agreed that we would not want to repeat the experience. Like the harpsichord, a little of the fortepiano goes a long way. I have always thought that the harpsichord has a highly distinctive sound which can vary from brilliant to creepy; there is a wonderful 20th century harpsichord concerto by the Swiss composer Frank Martin which demonstrates both these qualities. But it lasts barely 20 minutes, has an orchestra for contrast, and doesn’t outstay its welcome. I would reckon that is about the optimum for the fortepiano too.**

Some of what I had read about the fortepiano was borne out by this performance. Its tone was roughly halfway between the bright impermanence of a harpsichord and the rich resonance of a modern concert grand. The “sustain” on the fortepiano (that is, the period during which a note continues to be heard after it has first been struck, so long as the key remains depressed) was quite short. There were no pedals and Irving’s feet remained securely planted on the floor – Michelle though he might actually be wearing slippers. Particularly in the slow movements, this lack of sustain caused the music to drag. It’s easy to see why baroque and early classical keyboard music makes such extensive use of ornamentation (that is, the twiddly bits which are added around a central note); it is to fill what would otherwise be empty space. With a modern piano’s natural sustain, plus the use of its sustaining pedal where necessary, this problem doesn’t arise.

What I had not expected was a lack of any real variation in dynamics. “Fortepiano” in Italian literally means “loud soft,” but with one exception the whole performance seemed to me to be pretty much mezzoforte, neither one thing nor the other. In the complex part-writing of the Bach Prelude and Fugue, where a good performer on a modern piano will take pains to differentiate between the lines of counterpoint and bring out the themes wherever they occur, Irving’s tone was unvarying and the lower parts were indistinguishable from the surrounding notes. I am reluctant to criticise the performer for this; I think the fortepiano’s limitations made him unable to bring out the inner parts from within the surrounding contrapuntal texture. The exception was that Irving did consistently shape his musical phrases with a natural rise and fall, as I was taught in my piano lessons fifty years ago.

There was also a very noticeable variation in timbre between the upper and lower registers. This was a five-octave fortepiano (a modern piano has a range of six octaves and a bit), but most of this performance focused on the upper register which was bright and harpsichord-like, or the middle register where the sound was closest to a modern piano’s. The lower registers, anywhere more than an octave below middle C, had an unpleasantly reverberant, growly sound. I had read that the timbre on a fortepiano varied widely across its range, and this turned out to be true.

Towards the end of the concert I noticed a number of occasions when there seemed to be gaps in Irving’s passagework and ornamentation. Even the greatest pianist’s fingers have been known to slip from time to time, and at first I didn’t pay much attention. But when the apparent slip was repeated I came to realise that it was not the performer but the instrument at fault. On a fortepiano, like a modern piano, after a note is struck the hammer should fall back quickly into place, so a rapidly repeated note may be played with no loss of tone. But on an older or poorly maintained piano the hammers sometimes get stuck, or are slow to fall back, so when the key is struck again no sound is produced. I am pretty sure this is what was happening; the fault had evidently developed during the evening’s performance. It’s inconceivable that this would happen on a well-maintained modern concert grand, so to the fortepiano’s other drawbacks I think we must add that its hammer mechanism is highly sensitive and temperamental.

So: the fortepiano, in its own favoured repertoire, is a temperamental instrument with a distracting variation in timbre between its lower and upper registers. Its lack of sustain causes it to drag in slow music, and its dynamic range is a good deal less than claimed. I enjoyed my evening out with Michelle, but on the whole I will stick with my modern piano, thank you.

** : For the curious: Frank Martin’s Harpsichord Concerto can be heard at www.youtube.com/watch?v=IISJXKl1Ih4. The sound quality isn’t particularly good, but you still get an idea of how a modern composer can put the harpsichord’s qualities to use. I first heard this piece as accompaniment to a ballet based on Lorca’s play The House of Bernarda Alba. I’ve forgotten everything else about the ballet, but not the music.

——————–

Poetry and art

16 May 2017

A few days ago, Michelle took me to a private view of an exhibition in a small art gallery in London. This was not an ordinary exhibition. There is a small website you can look at (http://fitzroviagallery.co.uk/myportfolio/visually-literate-kaos-artists) but perhaps the best description can be found in the publicity material:

“Kingston Artists produced 26 artworks that included paintings, drawings, printmaking, photography, ceramics and video art. They then invited members of the Creative Writing courses at Kingston Adult Education to create stories, poems and flash writing, taking the artworks as their inspiration.”

Michelle joined one of the Creative Writing courses last summer and one of her poems was among the works exhibited. At the private view many of the artists and writers, and their friends and relatives, were present, and a selection of the writings were read aloud by their authors, including Michelle. Incidentally, “private view” is a gross misnomer: the gallery was hot and crowded, and apart from the readings I am sure I would have gained a better appreciation of the work on display if we had visited the exhibition on a “public” day.

Now, there is a bit of a backstory here. Since Michelle started in the class, she has from time to time sent some of her drafts to me and invited comment. This is flattering, but also dangerous. All artists welcome praise, but no artist particularly enjoys criticism, however well-intentioned. And I am no expert. True, I learned how to analyse and evaluate Latin and Greek poetry, but that is a very different thing.

My knowledge of poetry is, at best, patchy. I studied a selection of Browning’s poems for my English Literature O level, and all I can remember about them is that he was fond of the dramatic monologue. For some reason one sinister instance of this has stuck in my mind, his poem My Last Duchess.

While I was at Oxford I started trying to write songs for voice and piano. This was a time when I was experimenting with rhythm and harmony, trying to develop a style of my own, and was attracted (like Delius and Vaughan Williams, as I later learned) by the poetry of Walt Whitman, whose lines do not rhyme and follow no recognisable, let alone regular, pattern of rhythm or metre. I thought this might help me to break from the straitjacket of four-bar phrasing and standard time signatures.

I wrote half a dozen songs to words by Whitman, the longest and most ambitious of which was a setting of his poem Tears. Like much of my other music, it is at least as good if played by piano solo. I confess, though, that I was a bit puzzled by why some of Whitman’s work counted as poetry at all, since it had no obviously poetic qualities that I was able to recognise.

After Oxford my interest in poetry went into abeyance. It was not until ten or so years ago that I started reading poetry again. After Mum had her stroke in late 2004, we used to visit her regularly, first in hospital and then in the nursing home. She seemed to find it comforting to hear our voices, so we started reading aloud to her. We worked our way through Jane Austen’s Persuasion, as Austen was Mum’s favourite author, and were starting on Pride and Prejudice when my friend Anne made a brilliant suggestion: instead of more Austen, we should read poetry. It really should have been an obvious idea, but such was my (lack of) interest in poetry at the time that we never thought of it for ourselves.

So we obtained a couple of anthologies of popular poetry, and rapidly developed a list of favourites: T S Eliot’s Practical Cats, especially Macavity, large parts of which I can still recite from heart; Jenny Joseph’s Warning; F W Harvey’s Ducks; Shakespeare’s sonnet Shall I Compare Thee…; Kipling’s The Glory of the Garden; Shelley’s Ozymandias; D H Lawrence’s Snake.

This is a wide-ranging list, but prompts this thought: how difficult it would be, drawing on only these examples, to arrive at a simple definition or even description of poetry which would encompass them all. And yet my mind and heart rebel against the notion that anything goes. Something is not a poem just because its author says so. And a poem can be good or not so good, depending on how far it matches up to this indefinable Platonic ideal.

Wiki defines poetry as “…a form of literature that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language … to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, the prosaic ostensible meaning.” No doubt literary scholars would debate every word of this, and I think myself it is too all-encompassing: would not the great speeches of Demosthenes or Cicero or Churchill also fulfil this definition? But I do think there is something in the notion that poetry evokes meaning, and does so in part through the choice and quality of language. Though no doubt counter-examples could be found.

There is a corollary. If poetry evokes an unstated meaning, the poet needs to be careful only to evoke the meanings that he or she intends. This obviously applies to the choice of words. But it also applies to the other qualities possessed by poetry: rhyme, rhythm, metre, shape. So, for instance, it is unwise to allow one accidental rhyme in an otherwise non-rhyming poem, or a regular pentameter in otherwise irregular free metre. These things stand out; they imply meaning. For the same reason, repetition of words or phrases should be avoided unless it is done to make a deliberate pattern or underline a specific thought.

I have been searching for a quotation, which I remember hearing once, from the composer Richard Strauss. It was to the effect that anyone can think of a tune, but it requires skill to turn a tune into a piece of music. I actually think this is true even of a simple pop song, although in that case the artists are often to be found among the engineers in the recording studio, rather than the performers. It is certainly a truth I have discovered in my own music (though John would deny the presence of tunes): getting started on a piece is one thing, but working out how to continue and complete it is quite another.

I am inclined to think that the same may be true of poetry. Michelle’s poems (the ones which she has shown me) have each been based on an interesting idea. She writes arresting first lines, and she is also pretty good at steering each poem to its intended conclusion. Her poem in the exhibition seemed to me a valid and interesting interpretation of the artwork it accompanied, and was certainly one of the best pieces of writing on display. But I am a bit surprised that her Creative Writing class does not seem to be spending a bit more time on developing the kind of technical skills needed to carry initial concept to fulfilment: how to evoke meaning. I would myself greatly value this kind of help with the music that I write. Still, at least this leaves me something constructive to say when Michelle shows me a new poem and asks for comments.

By and large I thought the artworks in the exhibition were a bit better than the writing, though I didn’t think much of the video installation (trite) or the ceramics (meaningless). But I am even less knowledgeable about the visual arts than about poetry.

The poems mentioned above may all be found online:

My Last Duchess, by Robert Browning : www.poemhunter.com/poem/my-last-duchess

Tears, by Walt Whitman : www.poemhunter.com/poem/tears

Macavity, the Mystery Cat by T S Eliot : www.allpoetry.com/Macavity:-The-Mystery-Cat

Warning, by Jenny Joseph : www.poemhunter.com/poem/warning

Ducks, by F W Harvey : www.poemhunter.com/poem/ducks

Shall I Compare Thee…, by Shakespeare : http://www.shakespeare-online.com/sonnets/18.html

The Glory of the Garden, by Kipling : www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-glory-of-the-garden

Ozymandias, by Shelley : www.poemhunter.com/poem/ozymandias

Snake, by D H Lawrence : www.poemhunter.com/poem/snake

——————–

Village cricket

15 May 2017

Last weekend John and I spent a pleasant afternoon watching cricket at Kirkby Lonsdale. I had looked up which of our local teams, most of which play in the Westmorland County League, were at home, and we chose to visit Kirkby Lonsdale so John could take some photographs for his next year’s calendar. He has kindly provided all the photographs for this blog.

The home team were playing against Netherfield 3rd XI. (Netherfield’s first two XIs play in the more rarefied atmosphere of the Northern Premier League, alongside teams like Barrow, Fleetwood and Leyland, which are good enough to have nurtured several Lancashire county players.) We saw Kirkby Lonsdale batting, and one of their batsmen scored a century, a rare achievement at this level of cricket, reaching the landmark off the last possible delivery of the permitted 45 overs. I’d like to say he played an elegant, classical innings – but he didn’t. His main scoring shots were powerful leg-side heaves, and the bowling towards the end of the innings was not good enough to contain him. We also enjoyed the shouted encouragement from his teammates on the boundary as he neared the milestone. John and I both suspected that the last ball he received was a bit of a “gimme” from a chivalrous bowler – but he had played well enough to deserve a generous gesture.

When the players came off the field for tea we saw that Netherfield’s team comprised a mixture of boyish youngsters and grizzled veterans. We had already seen two of the youngsters bowling, a tallish fair-haired slow bowler (not much spin in evidence), perhaps 16 or 17 years old, and a very young leg-spinner, age no more than 13 I should guess, who bowled unchanged for something like fifteen overs. He did pretty well, too: the batsmen treated him with respect and he was never truly collared. He had the natural flight that comes from being short and he kept a fairly consistent good length, though his line did waver a bit, especially as he grew tired. I couldn’t see from where we were sitting how much he was spinning the ball but there was clearly some movement which beat the batsmen once or twice.

I was put in mind of Colin Cowdrey, who as a schoolboy was as much bowler as batsman, and took hatfuls of wickets bowling leg-breaks. A boy’s natural bowling action rotates the wrist as the arm comes over, imparting leg spin: it is only when the hands become larger and can wrap further around the ball that other grips, and thus types of bowling, become possible. As a boy, I bowled leg-breaks in this way – though erratically, and with no measure of success. Then, at about the age of sixteen, I learned to bowl the googly (which involves rotating the wrist still further) and, at the same time, completely lost the ability to bowl an ordinary leg-break. This, I understand, is also a familiar syndrome which has affected many other young bowlers.

But I digress. We came away at the tea interval so I could get home in time to cook our dinner, and so weren’t able to see Kirkby Lonsdale bowling. I did expect the match to turn out a comprehensive victory for them, but I now find (having checked the League website) that they were unable to bowl Netherfield out, so the result was a draw. Kirkby Lonsdale earned a few extra league points for a “winning draw,” whatever that is, but I am sure they will regard it as an opportunity lost.

Several of the local teams we have visited over the last four years play in this same league, including Coniston (who, like Kirkby Lonsdale, are in the second division), Silverdale (first division) and Cartmel (third). Many of the grounds are picturesque, especially Coniston, which is right up against the mountain on one side of the ground and slops down towards the lake on the other.

The cricket ground at Coniston, with the foot of the mountain to the left. You can just see the start of the downward slope on the right of the picture.

Cartmel actually have two grounds, one in the centre of Cartmel racecourse, the other in a corner of Holker Hall’s deer park. The Holker ground was created over the course of a winter, by favour of the Holker Estate, when it was known that the Cartmel ground would be unavailable the following summer. I hope it is still in use, though they did tell us at the time that it tended to be rather damp. John and I had an enjoyable afternoon there a couple of years ago.

We also sometimes go to watch cricket at Lindal (more correctly, Lindal Moor). This was a favourite visit with Dad when we were living at Woodgate. We had discovered the ground almost by accident one weekend: we noticed the back of a building on top of a hill which looked a bit like a scorebox, drove up the hill to investigate, and there it was. Lindal play in the North Lancashire and Cumbria league, a higher standard than the Westmorland League. Some 20 years ago they were good enough to have been in the Lord’s final of the national village cricket competition, and they have evidently invested in the ground, which has an extensive new pavilion, covers for the pitch when it rains, artificial-turf nets, and an improved model scoreboard to replace the one we noticed all those years ago. It is however a rather windy spot, and the ground has less character than Coniston or Holker or Kirkby Lonsdale. John has taken some photographs here too, but doesn’t think they are calendar material, and I can see his point.

Lindal was a favourite place to watch cricket with Dad, but it wasn’t the first. I can just about remember, when Mum and Dad first bought their weekend cottage at Woodgate, that Dad and I went out one afternoon in search of the cricket ground at Ulverston. We had to get directions, I forget how, and eventually found the ground in a field among the farmlands on the rolling hills west of the town – an unlikely, if picturesque, spot. One of the locals, with whom Dad struck up a conversation, remembered Ulverston’s most famous cricketer, Norman Gifford, who played for Worcestershire and England in the 1960s and 1970s.

However, we generally preferred Lindal, and so we were surprised one year to discover that Ulverston had abandoned their old ground and moved to a new one at a sports and recreation centre on the edge of town, near the industrial area. No doubt it was better appointed, but it had far less character. It also had a ridiculously short boundary where the pavilion intruded into one corner of the ground. Apart from this feature the cricket was a decent standard (the same league as Lindal), but the place was uninviting and we haven’t been back.

——————–

The hero and the muse

2 May 2017

When I was still in the sixth form at school, preparing for the Oxford entrance examination, our Latin teacher Brian Dobson gave us a short piece of Latin verse which he asked us to analyse. The excerpt was from the Aeneid, the great epic poem of nearly 10,000 lines which is widely regarded as the masterpiece of its author, Virgil, and one of the greatest poems ever written in Latin. Later, at Oxford, I would go on to read the whole poem, but at school we only studied short excerpts and the piece which Brian gave us was unfamiliar.

Reading Latin or ancient Greek poetry, and indeed prose, is a bit different from studying modern languages. No-one now speaks Latin or ancient Greek in normal life. You cannot go to ancient Rome or Greece to hear the language in everyday use, to learn the language through total immersion as many modern language speakers do. Indeed, our idea of what Latin and Greek sounded like is somewhat imperfect. For instance, there is a letter in Greek, eta, conventionally understood to be long E (while epsilon is short E). But when I was at school we pronounced it more like the er in term than the ee in beech. At Oxford I discovered that other pronunciations were also taught, but no-one could say which was truly authentic.

So for an exercise like Brian’s you have instead to observe the literary techniques used by the poet and try to imagine what was his purpose in using them. That, I remember, is how I tackled the question. Virgil uses a large number of figures of speech which are more or less familiar in English, like alliteration, metaphor and zeugma (look it up!). He adjusts word order to give emphasis, which is easier in Latin than English because Latin word-endings tell you what part they play in the sentence. He also uses variation in the structure of each line of poetry, not only to avoid tedious repetition from line to line (a technique used similarly by Shakespeare) but to bring out specific ideas. And finally, there are easily observed underlying themes in the Aeneid, themes of fate and duty, patriotism and religion, which can be found even in quite short excerpts.

The trouble with this approach to literary criticism is that it is easy to over-analyse. At Oxford my Latin tutor, John Bramble, was an expert on another Roman poet, Propertius, who was a contemporary of Virgil but is somewhat less well known today. Where the thread of meaning is fairly straightforward in Virgil, it is more difficult in Propertius. An article in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propertius) summarises the problems neatly: “The text contains many syntactic, organizational and logical problems as it has survived. Some of these are no doubt exacerbated by Propertius’ bold and occasionally unconventional use of Latin.” There is quite a lot of room for divergent interpretation, and I always suspected that John Bramble saw things in the verse that were not there.

But how can we tell? Much poetry, from Virgil and Propertius to Ezra Pound and T S Eliot, is intended to be interpreted, with layers of meaning that require to be uncovered. There is always also a possibility that some of what we observe in a poem reveals the poet’s unconscious, not their conscious, thoughts. An idea may be present even if it is not explicit, or even intended. But equally, if it is not explicit, it may not be present at all; it may be an idea which we have contributed for ourselves.

Which brings us back to Fire and Hemlock. In my blog on 15 April I said I intended to obtain a copy of the edition with Diane Wynne Jones’ essay on the writing of the book. I have now done so, and it is, indeed, a fascinating read, not just for understanding Fire and Hemlock but for a better appreciation of DWJ’s entire creative process.

DWJ seems to have had an unusual, and not especially happy, childhood. Her parents were teachers, but somewhat neglectful of their three daughters. The only books in their household were learned volumes or works of “serious” literature. So DWJ’s childhood reading encompassed Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, unabridged; Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey; Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales (that at least genuinely is a book for children); Pilgrim’s Progress; and an extraordinary volume of literary scholarship called Epics and Romances of the Middle Ages. DWJ had to plead with her parents for Andersen’s and Grimm’s fairy tales, and for the (bowdlerised) Arabian Nights.

One of the explicit themes in Fire and Hemlock is the hero. What is a hero? And what makes an act heroic? There is a simple version, modelled in DWJ’s childhood reading by Hercules or King Arthur, or for modern readers by Aragorn or Jack Reacher. This, more or less, is the version imagined by Tom and Polly in the stories they tell to each other. But it is not the one modelled by their own lives. DWJ asserts that Fire and Hemlock is her “personal version of the Odyssey,” an ancient myth with a very different type of hero, who does not prevail in combat but outthinks his enemies and breaks their enchantments.

The incidents of the Odyssey and of Fire and Hemlock bear, superficially, little resemblance. If you had not been looking for a connection it would pass unnoticed. To complicate matters further, in Fire and Hemlock the heroic role switches between the two protagonists. Nonetheless, when the similarities of theme are pointed out they become quite clear. In the crucial final scene, all that Polly has been through gives her the understanding to know the sacrifice she must make in order to break the enchantment.

DWJ acknowledges every one of the influences mentioned in my previous blog, and more besides. (Much of the analysis on the goodreads website, which I cited, is in fact not original at all, but recycling DWJ’s own words.) Her quotes from Eliot’s Four Quartets make it clear, and not fanciful at all, that they are a central influence on Fire and Hemlock, with its shifts between realities – “Here-Now” and “Nowhere.” She also offers an interpretation of the story of Cupid and Psyche (“a myth of the human soul in search of a beloved ideal”) and melds it into Polly’s coming-of-age story. “People do lose sight of their ideals in adolescence and young adulthood… the myth of Cupid and Psyche is certainly about this.” Eliot, Cupid and Psyche are not mentioned in the book, but they are present just the same.

It doesn’t matter if you read Fire and Hemlock without being aware of these undercurrents. It is still an excellent and satisfying story. Nor does it matter if, when you read Propertius or Virgil, you are only imperfectly aware of the technical underpinning of their poetry. However, what DWJ shows is that clever authors may use a wide range of techniques of structure and language to reinforce what they write. There is more going on than shows on the page. Perhaps John Bramble understood this better than I did.

There is one other feature of Fire and Hemlock, not mentioned in DWJ’s own essay, which I admire. In the course of the book Tom (a professional cellist) educates Polly in music. When she visits he plays LPs for her; when they are apart he sends her cassette tapes. In two crucial scenes, one when Polly, abandoned by parents, finds Tom’s quartet rehearsing in a Bristol concert hall, and again in the build-up to the final climax, DWJ tells us about the quartet’s music as Polly hears it. Describing music in words, with clarity but without being pretentious, is very difficult. But DWJ’s evocation of the music is just right. I suspect it is a metaphor, or a concealed story element. As Polly learns to listen she is also learning what Tom means to her. But even if you take the description of the music at face value and nothing more, it works.

I have always been fond of books with music in them (another quality, incidentally, of Patrick O’Brian – see blog on 26 April). Just another reason to admire Fire and Hemlock.