Patrick O’Brian

26 April 2017

At the start of the seven weeks of my radiotherapy, I decided I would commit myself to a long course of reading while I was waiting my turn for treatment. I don’t mean to imply that the radiographers kept a lax schedule; on the contrary, every appointment was met within a minute or two of its scheduled time. But I was required to drink 450 ml – about a pint – of water 45 minutes before each treatment, so I knew I would be waiting around meanwhile.

The books I chose to read, or in some cases re-read, were the novels by Patrick O’Brian whose protagonists are Captain Jack Aubrey of the Royal Navy and his regular seafaring companion Stephen Maturin, who is doctor, naturalist, political adviser and intelligence agent. O’Brian died in 2000 and at that time he had completed twenty books in the series. He had started work on a twenty-first, but left it less than a third complete; the fragment has been published, but I am content just to have the twenty.

I started in late November and finished around the end of March. The books lasted a lot longer than the radiotherapy, and I have read other things in between times, about which I have written in other blogs. Nonetheless, I gave O’Brian enough continuing attention to build my sense of the series as a whole, the shape and development of his characters’ lives and careers.

The earliest of the books, Master and Commander, was published as long ago as 1969, and though O’Brian continued to publish new volumes at regular intervals, the series was at first a modest success. That all changed in the late 1980s when he caught the attention of a number of influential critics, on both sides of the Atlantic, who queued up to offer their praise. O’Brian’s work became for a while both celebrated and popular, and a film was made, Master and Commander (2003), which drew on storylines and incidents from some of the books. More recently, however, interest seems to have subsided. The books are all still in print, but are only on the shelves at the largest bookshops, and not always then.

Of course there are fashions in reading, as in other entertainments. Perhaps it is more a matter of surprise that, in the age of Dale Brown and Jilly Cooper, O’Brian was ever fashionable at all. It isn’t possible to skim one of the Aubrey/Maturin novels; your full attention is demanded. For one thing, they provide complete immersion in the period and milieu. The language used by the narrator, as well as the dialogue which he gives his characters, is appropriate: courtly, elegant, spacious. Not a word that would be out of place in the early 19th century. Nor is any special consideration given to a modern reader’s possible ignorance of the general historical background, let alone the workings of a sailing ship. O’Brian delights in his technical expertise and he makes free use of nautical terminology – masts, sails, ropes, gunnery, ranks. Occasionally a sailor explains some technical point to the lubberly Maturin, but if that trope were too often repeated it would become obvious, and O’Brian is rarely obvious.

He also has an unusual attitude to shape and narrative. A few of the books are self-contained: The Mauritius Campaign, fourth in the series and one of my favourites, is one such. However, although they generally start gently enough, picking up the threads from the previous volume, they often end abruptly, with no wind-down or tying up of loose ends. O’Brian just doesn’t seem very interested in this kind of novelistic neatness. And as for narrative, although he uses a simple time-frame which moves steadily forward, and writes very few scenes in which neither Aubrey nor Maturin is present, he often leaves sudden, unsignalled lacunae between one scene and the next. Fair enough: why should he write anodyne paragraphs to describe periods, no doubt frequent enough on shipboard, when nothing out of the ordinary is happening? But the jump-cut effect is disconcerting, especially when it happens – as it often does – after a scene of action.

A casual reader may also be disappointed if expecting stories in the vein of C S Forester (Hornblower), Dudley Pope (Ramage) or Alexander Kent (Bolitho). There are numerous accounts of naval combat in O’Brian, very often based on real-life actions which he has meticulously researched, but they are not the point of the books. Nor are the occasional lengthy storm sequences, although they feel extraordinarily realistic. A reader seeking excitement will have to hunt for it.

The books have action and humour, passion and pathos, intrigue and romance. But above all, consistently through the entire series, they are novels of character and manners. Aubrey and Maturin are both surpassingly well drawn. Aubrey, the simpler man, is a lion at sea but a bit of an ass on land, and could have devolved into something of a caricature. But through a variety of touches he is fleshed out. What most impresses about Aubrey – and you really need to read the entire series of books from first to last to realise this – is how convincingly his character develops and changes with the passage of time. The adventurous, passionate, headstrong young captain of Master and Commander is barely recognisable in the imposing, authoritative, severe figure of Blue at the Mizzen, and yet we have seen every stage in his transformation.

While Aubrey gets older, Maturin seems almost ageless, yet we are never bored with him. He is a far more complex figure whose various facets we only gradually understand. Unlike Aubrey, he is subtle and self-aware, almost morbidly so. He is a man of the stiffest honour and highest principle, and a doctor of uncommon skill for the period (I do wonder whether O’Brian may have stretched plausibility a bit in this one respect). But he is also a complete lubber, constantly puzzled by naval jargon and custom, though cosseted by the crews who value his skills; and his relationships with women – not just the beautiful Diana Villiers, whom he pursues through many books, but several others – are a tangled mixture of worldliness, naivety and passion.

O’Brian himself asserted that “…The essence of my books is about human relationships and how people treat one another.” I agree. The reason why the books are so fascinating, for all their impenetrable jargon, obscure (to me) historical background and eccentricity of narrative, is that none of these things is central to their enjoyment. What O’Brian does is describe human relationships in the context of a society – more correctly, two societies, one on land and one at sea – with rigorous codes of behaviour, yet constantly under stress. Although he focuses on his two protagonists, he also provides us with a wealth of recurring and secondary characters, male and female, who are deftly portrayed and clear to our minds’ eye.

And yes, the books are funny too. Aubrey loves a pun, and makes the most of any he happens to come across. He is also a famous mangler of proverbs, for which he is regularly teased by Maturin. As for Maturin, his lubberliness provides us and Aubrey’s crews with regular amusement, and his obsessions with the natural world create frequent opportunities for farce. Who can forget the drunken sloth in HMS Surprise? But you never feel that O’Brian is laughing at his characters. The humour is affectionate.

As the series approaches its conclusion, it is possible to see a slow waning of O’Brian’s powers. There is more repetition and padding. Various characters are written out – they are killed off, or simply disappear from view – and their replacements, except perhaps the eager youngster Reade, do not have quite the same lustre. That said, O’Brian was 86 when he died, and still writing. Some falling-off seems forgivable.

The Aubrey/Maturin series as a whole is surely without parallel in all of English literature. It far outshines Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, whose twelve volumes already seem faded. The nearest equivalents I can think of are the Lymond and Niccolo series of historical novels by Dorothy Dunnett, but I do not think that Dunnett, who makes more use of the exotic and byzantine, will be remembered in fifty years’ time. O’Brian surely will.

——————–

Three railway games

22 April 2017

Just in case anyone thinks that my interest in railway timetables, layouts and maps described in my previous blog is a little unusual, here are one venerable and two recently published computer games which cater for people just like me. These games have been very successful with critics and players alike.

The Europe map from Railroad Tycoon. The set-up has just been completed so no railways are yet visible.

Railway games have existed from the very early days of the PC. One of the finest is still Railroad Tycoon – the original game, not one of the various updates or remakes. It uses a large scale playing area (England, Europe, Western or Eastern USA) with more or less realistic geography. You start with a certain amount of cash and shares in your company, and build railways to connect various towns and industries with markets and destinations.

A small zoomed-in section of the map. This is where you build tracks and operate trains. The underlying grid has been switched off but can be easily inferred.

The playing area on which you build is a square grid. Each cell in the grid has a spot height, so gradients are among the issues you must consider when building your railways. Cities grow, semi-randomly but stimulated by the traffic you provide. Industries likewise appear and decay, so your network needs constantly to grow and change. And there are three other computer-run networks competing with you who will try to take you over if you let them. Of course you can take them over too.

Alas, Railroad Tycoon was built for the original MS-DOS operating system, and is difficult to run on modern PCs. I have not played the game for some years, but it is still fresh in my mind. Other railway games have come and gone, but only in the last twelve months have I come across two which, though on a smaller scale, have the same addictive quality as Railroad Tycoon. Yet they are very different games.

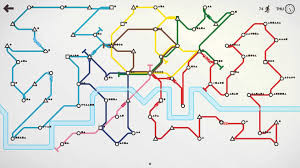

The first of these is Mini Metro. You build and grow a metro network in one of a number of different major cities. The network is represented by a map with strong similarities to the classic London Underground map. You can build up to seven different lines with up to four trains on each, but you may only add lines or trains, or other facilities like cross-river tunnels, when they become randomly available to you at the end of each game week.

Early in a game. You can see an empty train on each line, the three main station types and some waiting passengers.

Every game of Mini Metro is different. Stations appear randomly on the map, whose area gradually increases as the game progresses. They are represented by different symbols, and passengers by small versions of those same symbols. Each station receives passengers of its own type and randomly generates passengers of different types. Each train carriage may carry up to six passengers. Eventually your stations become too crowded because your network capacity has not kept up with demand. The game ends and your score is how many passengers you have successfully carried to their preferred destination. You are doomed always to fail: gameplay is all about how long you can keep going.

The best I have managed so far is a score of just over 2000, which represented several weeks’ game time and took about an hour to play through. By contrast, a game of Railroad Tycoon could easily take a week real time, allowing for food, sleep, work, shopping and exercise. Mini Metro is thus one of an increasingly popular class of “casual” games which can easily be fitted into a spare hour. I play it on my desktop PC but it runs well on laptops or tablets, so is just the thing to keep you occupied on, say, a long train journey.

A Mini Metro game in its late stages on the London map. Passengers are queueing at the stations. Most of the lines have been arranged in loops. But the map does not look very realistic.

One of the best things about Mini Metro is that it is, within limitations, quite strategic. You need to think about the shape of your network (loops are better than point-to-point routes), the stations served by each line (needs to be a good mix so waiting passengers don’t build up too easily) and how to avoid too many river crossings (since the number of tunnels available is limited). These considerations don’t always mesh and you have to watch out for when they don’t.

However, there are also three things I dislike: the game always ends in failure, which is a bit of a downer; the random generation of key elements, especially tunnels, can thwart the best laid plans; and, frankly, the maps end up looking not remotely like any metro network I have ever seen. Still, you can’t have everything. If you are interested in building networks this is about as good as it gets.

And second, another “casual” game: Train Valley. This one has the advantage that you get both to build the networks (and, unlike Mini Metro, have to stay within a budget too) and to despatch the trains. Most of the maps are predesigned – there seem to be about 30 of them – and stations appear on them in the same places each time, though not always in quite the same sequence. Nonetheless, the effect is that you can “learn” a map so as to play better next time. I’ve played 20 maps so far and I’d say that I have completed most of them the second time around.

A Train Valley game in progress. The train in the middle has just avoided one collision at its rear, but another now seems inevitable just ahead. The red box above the engine shows its intended destination.

Although effective layouts can be worked out for each separate map, train despatch seems to be totally random. Each station is allocated a colour and each other station may generate trains baring a flag of the same colour to show where they need to be sent. With a few exceptions all trains move at the same speed, but new trains waiting to be despatched appear every few seconds. You need to be really alert for the right moment when the route is clear and not to make any mistakes with how the points are set.

You will often have several trains running at the same time, and the challenge is to get them all where they need to go without causing collisions or sending them to the wrong stations. As the game proceeds you may need to build more and more complex layouts with multiple redundancy to keep the traffic moving. If trains are kept waiting too long, they depart without waiting for your all-clear, and then you are really in trouble.

Once you have solved the track-laying puzzle, the essence of this game lies in the despatching, which makes it a very different experience from Mini Metro. Each game is complete in 10 minutes or less, so the amount of trial and error involved does not become too frustrating.

As a general rule I dislike games which are too scripted – that is, for which you have to find the single unique solution: that’s not strategy, it’s puzzle-solving. This is, for me, one of Train Valley’s two defects. However, every sixth map is less scripted than the others. Station locations are still predetermined, but the geography can be quite different from one playthrough to the next, so on these maps there really is no optimum solution. I would have liked there to be more of these.

My other problem with Train Valley is that the layouts can end up looking ridiculous. They look much more like model railways than the real thing. On the other hand, you do get to see actual trains running, and can even zoom in to see them in more detail, though there is no gameplay advantage that I can see in doing so.

One crucial feature of all these games is that, while they play continuously (that is, gameplay is not divided into turns), the game can be paused at any time so you have a chance to think. Games without a pause feature require dexterity more than strategy, and don’t interest me much. They are often used in online games which I do not care for at all. If you want to play with other people, board games are the way to go, and then instead of total strangers you can play with family and friends. The computer is for when you have no other opponents.

——————–

The railway craze

18 April 2017

John asked for this blog. I hope he likes it.

All the male Liverpool Coulsheds have been fascinated, one way or another, by trains. I suppose it must have begun with Dad. What the origins of his interest were, I don’t know, but from the age of a very small boy I can remember him taking me to see the trains, and I think he was as excited (in a grown-up sort of way) as I was.

Our favourite place was on a side road near Mossley Hill station in Liverpool, where only metal railings separated pedestrians from the railways and we could watch the London expresses thundering by. At one time there was a footbridge too, but it was taken down when overhead wires were erected for the electric trains. We used occasionally also to sneak through a doorway on Picton Road railway bridge near Edge Hill station, where there were often steam engines awaiting their next run. And I can just about remember a cast iron footbridge over the railway at Brunswick Dock, between the tunnels on the old Cheshire Lines route into Liverpool Central.

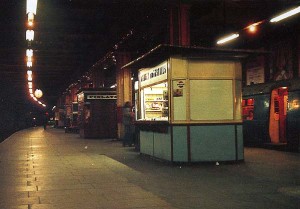

Liverpool Central Low Level in 1975, just before modernisation. No picture can do justice to the dank atmosphere.

Dad (and Mum) used to take me on train journeys as well. Occasionally Mum took me on the electric trains from Liverpool Central Low Level to West Kirby or New Brighton. I have a vivid memory of the Low Level station, a single island platform in a tunnel, with trains terminating on one side, reversing at a headshunt beyond the platform, and departing again from the other side. There had been only electric trains on the underground lines for more than fifty years but there was still, astonishingly, a smell of damp soot in the tunnels.

Mum used also to take me on the Liverpool Overhead railway. That closed in 1956 when I was only three years old, so my memories are a bit fragmentary. Nonetheless I do remember a couple of odd details. The rails were mounted not on conventional sleepers of wood or concrete, but on a sort of corrugated base which I imagine was part of the cast iron girder structure whose decay eventually led to the line’s closure. There were two types of trains, one with older carriages that had slam doors and one with new-fangled sliding doors which I (naturally) preferred. I also remember the terminus at Dingle where the overhead briefly went underground. It wasn’t smelly like Central Low Level, but it was dark and dingy. We didn’t go there very often.

However, my favourite trips were on the diesel multiple-unit trains from Liverpool Central to Gateacre or (even better, because a longer trip, and semi-fast) from Liverpool Lime Street to St Helens. In trains of that type, there were windows between the driver’s cab and the passenger compartment immediately behind, so by sitting in the front of the compartment I could have a driver’s-eye view of the line ahead. Sometimes it was a first class compartment and I went through agonies wondering what would happen if we were caught travelling first class on second class tickets. Modern trains, alas, do not have windows for the passengers to look ahead. I suppose drivers eventually complained of distraction from the compartment behind them. On the Manchester trams, and anywhere else I can look ahead past the driver, I still like to sit as close to the front as I can.

When we went on holiday I used to pester Dad and Mum for other chances to travel on diesel trains. When staying with Uncle Jim at Solihull, Dad and I went by train to Birmingham Snow Hill and back. When staying at Marske in North Yorkshire, we went from Saltburn to Middlesbrough, and on the Middlesbrough to Whitby branch, which was interesting because at Battersby the train reversed direction. In North Wales we went from Pwllheli to Caernarfon – though that journey was cut short: a tunnel just short of Caernarfon was flooded and we had to complete the trip by bus. Our archive of 8 mm movie footage shot by Mum and Dad includes brief clips from the Whitby and Caernarfon adventures.

Banks railway station in 1963, seen from the level crossing, looking towards Preston. Signalbox on right.

Of course I travelled on steam trains too. In particular, Grandpa C and Grandma (Dad’s parents – Mum’s father was Grandpa B) lived only a couple of hundred yards away from the railway at Banks, near Southport. It was a red-letter day when the signalman invited me in the signal box at Banks station; I remember that I was completely unable to move any of the large mechanical levers he invited me to pull. Grandpa and Grandma sometimes took me in to Southport or out to Preston, and the train was always hauled by a steam engine. Diesels were never introduced on the Southport–Preston branch line, which was closed as one of the Beeching cuts in 1964. I don’t think BR tried very hard to save it. Much of the land was taken for roads or housing development.

The West Lancashire Railway between Southport and Preston. Left-click on this image to see it in better focus.

I was just fifteen years old when the “last” steam train ran on British Rail, in 1968. (No-one then foresaw the advent of enthusiasts’ steam specials running on the national network.) David was not then quite eleven years old, and John was just four. John has no memory of being hauled by steam and I suspect that David is the same. So it is a little odd that it is they, not I, who have been bitten by the steam nostalgia bug.

Or perhaps it is not so odd, after all. I spent more than 25 years commuting by electric train between home and work – a journey which would have been slower, dirtier, less comfortable and less reliable with steam. For years I have also travelled regularly between London and Liverpool, Manchester or the Lakes, a journey which takes half the time it did when trains were steam hauled. I still find railways fascinating, and enjoy travelling by train, but I have no special regret for the days of steam.

David and John will go out of their way to see a steam train if one is running nearby, and will pay significant sums for the pleasure of travelling on an enthusiasts’ special hauled by a steam engine. You can see the evidence in their blogs. And they are not alone. There must by now be only a small proportion of the population who have any clear recollection of steam in service on British Rail, let alone travelling on a steam train, but the enthusiasts’ hobby is flourishing. It would be nice to think it is more than just a branch of the wave of nostalgia sweeping the country.

To be fair, I can see why people like to watch steam engines in action. With a steam locomotive, you can see and hear the power at work. When an electric train goes by, all you can admire is the speed; nothing else is on display. But a steam engine has an aura. John and I went to Carnforth last year where we and about a hundred other people watched a steam-hauled special, puffing and hissing as it passed by.

But for me the greatest interest has always been in the organisation and operation of the railway – track layouts, signals and timetables. As a small boy I used to draw extensive railway layouts on the beaches in North Wales with a “railway-lining stick” (stick with a double prong) which Dad made for me. Later on, well into my teens, I used to draw up imaginary timetables for real railway lines. Drawing on my collection of Ordnance Survey maps, I would invent complex suburban networks using existing or abandoned railway lines around cities – Nottingham was a favourite. When Dad and I travelled round the railway using Railrover tickets in 1966 and 1967 (I went on my own in 1968) I scoured the timetables to draw up itineraries that visited the most far-flung routes for which our tickets were valid.

Between 1999 and 2003 I was head of the Railways Sponsorship division in the Department of Transport. This was the period during which Railtrack was replaced by Network Rail, and my name can still be found online in a couple of the documents that were cited in the fractious legal case which followed, but in fact I was carefully excluded from the whole of the Railtrack affair: I was left to get on with other aspects of railways policy.

My job in Railways Sponsorship was not quite as interesting as you might imagine. But I am still proud of my part in the process which led to double track being restored between Bicester and Banbury, thus reinstating a link which has enabled the Chiltern rail franchise subsequently to flourish. I didn’t talk about it to Mum and Dad, but I think they would have said it was Destiny.

——————–

Fire and Hemlock

15 April 2017

This is a blog I wasn’t expecting to write, about a book I wasn’t expecting to read, by an author to whom I hadn’t previously given much thought.

After John and I drove up from Oxted a few days ago, I relaxed for a while in John’s house in Manchester before completing the drive to Cark. While I was there I browsed through John’s bookshelves and found in one corner a small collection of books by Diana Wynne Jones.

DWJ is best known as a children’s author. She wrote the book on which the internationally successful Japanese animated film Howl’s Moving Castle was based. John is very keen on Japanese animated films, of which he has a large collection, so it stands to reason that he would buy the book of the film, together with DWJ’s two sequels. I was not much interested in those. But alongside them was Fire and Hemlock, and I picked it up.

Now, six days later…

The first thing to say is that this is only superficially a children’s book. DWJ (who died in 2011) was a prolific author, and wrote variously for different age groups, including a handful of books, of which this is one, that seem more naturally intended for a young adult market, in the same way as Guy Gavriel Kay’s Ysabel (about which I have written previously) or Alan Garner’s The Owl Service. I don’t think DWJ’s publishers have done her much of a favour in this respect: the cover of the latest edition is styled exactly like her books intended for children, and this may discourage potential readers.

Fire and Hemlock has quite a lot in common with the Garner, not least in its background of fractured families, and in the intrusion of ancient myth and folklore into the modern world. The Owl Service is based on a tale in the collection of Welsh legend, the Mabinogion. Fire and Hemlock takes as its starting-point two Scottish ballads, Tam Lin and Thomas the Rhymer; both can apparently be found in the Oxford Book of Ballads, which I must now consult if I can lay my hands on a copy.

The plot is difficult to summarise as it involves at least two, probably three, different levels of reality, and the narrative shifts between them without obvious warning (although clues are given if you are reading really carefully). Indeed, beyond the simple level of what happens next, a lot of what happens in the book isn’t at all obvious, even on re-reading; in the last six days I have read it twice, the second time to see if I could work it all out. The core is that a chance meeting between Polly, a ten-year old girl whose parents are about to be divorced, and Thomas (Tom) Lynn, who turns out to be a professional musician, develops into a friendship, with occasional meetings and more frequent letter-writing. (There are no computers, or email: the book was published in 1985.) In the course of that friendship various unlikely and inexplicable events occur until it eventually becomes clear that Tom is in thrall to the Queen of Fairy, as is Tom Lin in the ballad, and it requires an act of heroism by Polly for him to be freed.

This really is only the core: there is a lot more to it than that. For one thing the time span of the book is nine years, and over that time Polly grows up. We see her at school and with her friends, and in her dismal home life with wholly inadequate parents. If this were a purely mundane kitchen-sink book about growing up in a broken househiold it would still be a pretty good one. As it is, if we did not know the author and had not read the blurb on the back cover, we would be three quarters of the way through the book before we could be sure that this really was a fantasy at all (although there are some strange coincidences half way through that I suppose would take some swallowing).

For another, there is a strong continuing contrast between Polly’s wretched home life and the world of imagination which she shares with Tom. Perhaps DWJ’s most striking piece of craftsmanship is how the fantastical gradually intrudes, and yet at the same time how the outlines of the story become more blurred, until the climactic scene which is, quite extraordinarily, left open-ended. You really have to read every word carefully, and even then may not be sure whether there is a happy ending, or at least how happy it is. Some readers, commenting online, have enjoyed the rest of the book but find it hard to come to terms with its conclusion.

And yet the clues are there to be spotted if you care to pay attention. Armed with foreknowledge, I was able for instance to spot a bit of dialogue quite early in the book where Sebastian says to Polly: “You didn’t eat and you didn’t drink…” Anyone who knows the story of Persephone should recognise that one. But there is a lot more that took consideration and re-reading for me to grasp.

A book about an evolving relationship between a girl, initially just ten years old, and an adult man might easily have undesirable overtones. I understand that it has been banned by some school teachers and librarians on that account. DWJ was clearly aware of what she was doing: Polly’s mother and Granny both warn her about the dangers of associating with “strange men,” but are somewhat reassured when they meet Tom for themselves. And in fact the relationship isn’t quite innocent, since Tom (as we eventually see) needs to be rescued, and thinks Polly might just be the one – he, too, knows the story of Tam Lin. But by then we also know that he really needs rescuing, and only the most hard-hearted reader, surely, could fail to forgive him.

Unlike much other fiction in either kitchen-sink or fantasy, genres which are prone to taking themselves very seriously, Fire and Hemlock is often also laugh-out-loud funny. And its narrative, even if obscure, has an unputdownable quality too. A crisis is clearly coming, but only at the very end do we see what form it will take. Some readers have commented that after the lengthy build-up the dénoument comes and goes too fast, but is this not the nature of much real life? The crucial moments are upon us, past and gone, almost before we realise; only afterwards can we see whether we handled them well.

Fire and Hemlock is notable, too, for its literary connections. Part of how Tom wins Polly’s friendship and confidence is by sending her books – it is clear that within her family she is book-starved – and DWJ clearly took trouble compiling a list of what are, in effect, her own recommendations. Polly starts with Henrietta’s House, proceeds to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Sherlock Holmes and The Three Musketeers, and ends up with The Golden Bough. At Oxford, where she is found at the start and end of the book (most of which is in flashback), she is studying English, and no wonder.

But the literary quality also extends to DWJ’s own writing. On the goodreads website (http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/367158.Fire_and_Hemlock) there are almost 300 comments on the book, some of them very lengthy and learned, observing sources which range from the ancient myth of Cupid and Psyche to T S Eliot’s Four Quarters (yes, really). DWJ apparently admits the Eliot influence herself in an essay accompanying some editions of the book – not John’s, but I’ve ordered a copy.

I am twenty years too old to have read Fire and Hemlock as a boy, which is a pity as it would have shown me that fantasy can be written in more ways than one (I grew up with Garner, C S Lewis and Tolkien) and I would have learned things from it about how girls think and see the world. Despite its female protagionist this is not just a book for girls, or indeed for children (or young adults) at all. If you have read it you will know what I mean. If you haven’t, you should.

——————–

Two Stoppard plays

13 April 2017

John and I had the unusual opportunity last week to see two fine plays by Tom Stoppard on consecutive days: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, at the Old Vic, and Travesties, at the Apollo theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue. Travesties was an original production by the Menier Chocolate Factory in Southwark which had quickly sold out there and transferred to a larger theatre in the West End. I saw R&G thirty years or more ago, but missed Travesties when it was first performed; John had never seen either play. Georgina came with us to R&G but not to Travesties.

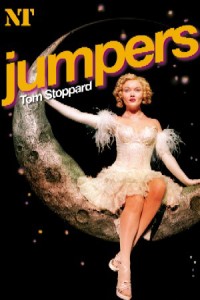

R&G was Stoppard’s first big hit, in 1966. Travesties was his third, in 1974. In between came Jumpers, which John and I saw a few years ago, and I also saw in its original production with Michael Hordern and Diana Rigg at the National Theatre, which I thought showed the play to be a masterpiece, quite unlike any other theatre I had seen. The revival did not quite reach the same heights but I still think that Jumpers is a very fine play which deserves to survive for future generations.

These three major successes established Stoppard as one of the most important modern British playwrights (he is Czech by birth, but his upbringing was in an English household). “Stoppardian” became a term describing works with what was perceived as the character of the three plays, using wit and comedy while addressing philosophical concerns. However, not everyone was equally impressed. A contemporary criticism made of his work was that it was somewhat heartless: “pieces of clever showmanship, lacking in substance, social commitment, or emotional weight.”

Whether or not stung by this criticism, Stoppard in his later plays advances towards realism, though the wit, philosophy and stagecraft are still present in abundance. John and I have seen his play Arcadia twice, in different productions, and I now think that that, rather than Jumpers, is his out-and-out masterpiece: as well as its cleverness it has a hefty emotional punch. I have not seen, and expect never to see, any modern play to match it. This view is widely shared by the professional critics. Charles Spencer in the Daily Telegraph wrote “I have never left a play more convinced that I had just witnessed a masterpiece,” while Johann Hari of The Independent speculated that Arcadia would be recognised “as the greatest play of its time.” Even The Guardian’s Michael Billington, who prefers theatre to be radical and is not, therefore, Stoppard’s greatest admirer, commented that Arcadia “gets richer with each viewing. … [T]here is poetry and passion behind the mathematics and metaphysics.”

So: how do R&G and Travesties match up against this standard?

True, neither play wears its heart on its sleeve. But I do not think Travesties, at least, lacks heart. Its central figure is Henry Carr, a minor British consular official in Zurich, now in his dotage. The play represents his confused memories of a period when he met Lenin, James Joyce, and Tristan Tzara who was a central figure in Dadaism. I had not understood that Tzara was a real person until I read the programme notes.

The Stoppardian wit is present in abundance. In one extended passage the dialogue consists of limericks (many started by one character and continued by others) which is both clever and hilarious. There are constant references to The Importance of Being Earnest, in which Carr once performed with Joyce; two of the play’s characters are called Gwendolen and Cecily, between whom there is an extended dialogue parodying a popular Vaudeville song, Mr Gallagher and Mr Shean. Several of Wilde’s jokes are borrowed or modified, notably a recurring riff on “the other one,” used by Stoppard variously to refer to characters in Earnest or in his own play. Scenes flash by in a disjointed order, reflecting Carr’s broken memories.

Yet in the background are serious philosophical questions about art and memory, war and revolution.

It all sounds like a hopeless mess; Stoppard’s genius is that he makes it work. And at the forefront is the figure of Henry Carr, brilliantly played in this production by Tom Hollander, whose confused memories are shot through with flashes of insight and passion. The only previous time I had come across Hollander was in the TV series The Night Manager, in which I did not find him wholly convincing. Playing Carr, he showed me that he is in fact a very fine, charismatic actor; so perhaps in The Night Manager it was the direction, not his performance, which I should have found lacking. Lenin, Tzara and Joyce are nicely played too, and Stoppard characterises them deftly, but it is Hollander who holds the play together.

If the heart in R&G is slightly harder to find, that may be because of its central conceit. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are two minor characters in Hamlet whose only function is to act as messengers and who end the play dead. Stoppard presents us with their lives offstage, except that we also see the scenes in Hamlet in which they appear (and speak their lines as Shakespeare wrote them), and a few other scenes in which they are shown as onlookers. He thus imagines them as real people, except that they have no memory before the play begins, and eventually realise that their fate, too, is scripted.

In Shakespeare R&G are little more than props, but Stoppard here has given them personality. They have been carefully cast for their similar looks, but Guildenstern (Joshua McGuire) is the more active and optimistic, and has most of the dialogue; Rosencrantz (Daniel Ratcliffe, yes, he who played Harry Potter on film) is more reserved, pensive and wary. They are on stage for virtually the whole play, so their star billing is well earned; and their acting skills are well displayed, in the quick-fire wit of Stoppard’s dialogue, in the seamless transitions from play to play-within-play and back again, in little touches which draw out their different characters.

They are however in some danger of being upstaged. In Hamlet there is a play within a play, put on by a troupe of travelling actors. That troupe also has a part in R&G, and their leader is played by David Haig in a wildly over-the-top show of histrionic bravura. He has an answer for everything; he is touched by no existential doubt. Yet like R&G he was called into existence to play a role, and when the play is over he will cease to be.

Beneath its absurdist premise and witty veneer, R&G invites us to consider fundamental issues: what is the meaning of life, and how should we face death. The play has been compared to Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (which John and I also saw, with Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart, a few years ago), but where Beckett has only nihilism and despair, Stoppard offers wit and varieties of courage. Is Beckett criticised for lacking heart? The question is beside the point.

It is true that Stoppard makes demands of his audiences, at least if you are to get the most from these two plays. You need to know your Shakespeare and Wilde (and perhaps your Beckett too). If all you get from R&G and Travesties is the wit, you have missed half the experience. What I liked about these plays, apart from the very fine direction and performances, is that they do not condescend. I have been to several shows recently where challenging originals have been toned down or adapted in various ways for modern audiences; it is demeaning, and generally weakens the plays so their impact and value are lost. Stoppard expects you to think as well as to laugh, and these two shows give him full value on both counts.

——————–

Grey vans

9 April 2017

John and I drove north today from Oxted to Manchester, and then I drove on to Cark, leaving John behind in Manchester where he has a couple more days’ work to do before the Easter holiday. He will join me here on Tuesday evening.

We set off from Oxted at about a quarter past nine, that is quarter of an hour later than I had hoped but close to what I had expected. I drove the first long stint, all the way to the Norton Canes service area on the M6 toll road round Birmingham, though we did also have a short break at Oxford services. Then John took over and drove us to the Boot Inn at Boothsdale near Kelsall in Cheshire, a few miles east of Chester. I did the map-reading. We took an unfamiliar route, leaving the M6 at junction 18 and passing through Winsford, which I now realise is a contender, alongside Kidderminster and Horsham, for the unofficial Great British Roundabouts competition of which the current undisputed champion is Basingstoke.

We first went to the Boot Inn some 10-12 years ago, when Mum was already in nursing care but Dad was still somewhat mobile. David was in the UK and had obtained a copy of the Good Pubs Guide. We visited four different pubs recommended in the Guide, including one where David was infamously bitten by a mole (yes, really), but of the four the Boot was clearly the best and we have been back on several occasions since. It is a large pub with a spacious dining area as well as outdoor tables, and serves excellent food as well as so-so local ales. There is also a field with a donkey which will sometimes come and make friends with visitors. The pub is a favourite with walkers, and publishes a little booklet with a map of walking routes in the surrounding area. John and I tried out one of those walks a couple of years ago and it was quite pleasant, though I must say I always prefer to have my trusty Ordnance map ready to hand.

Usually I make a reservation for lunch, but today we had to risk it as there was no guarantee when we would arrive. So we were rather disconcerted to find the car park, which is large enough for about 40 vehicles, more than three-quarters full, though on reflection, this being one of the first really sunny weekends of the year, we should not have been surprised. Anyway, we were fortunate to get a table in the bar area and had the usual excellent lunch. John ate all his roast duck and a good part of my roast beef too; my appetite is not what it used to be.

After lunch John took the wheel again and drove us on to his home in Manchester, where we stopped and had a cup of tea. Then I sat in an armchair for half an hour and read one of John’s books before getting back in the car and driving north to Cark, where I am writing this. As usual, the house was a bit chilly when I first arrived, but not as much as in midwinter: cold enough for two pullovers, but not for three.

This was altogether a much more trouble-free journey than I had expected. The M40 northbound is not usually too bad, but today the M25 clockwise, though busy, had no hold-ups, and the M6 was no worse. Most of the traffic seemed to be going in the opposite direction, and there were a couple of longish queues of which I took note: I shall be going back that way in a week’s time.

On several stretches of the M6, work is under way to create “smart motorways” – that is, where signal gantries enable variable speed limits to be operated, and where the hard shoulder may be used as a carriageway when traffic is heavy. But the 50 mph limits which apply through the roadworks, and are enforced by average speed cameras (as John never tires of saying, they may be only average but you still have to watch out for them), seem to keep the traffic flowing. I wrote a few weeks ago about my admiration for the project management on the Thameslink railway project works east of London Bridge, but the management of motorway improvements, keeping the traffic moving while works are carried out alongside, is also pretty impressive. But I really wish I had invested money in the company that makes traffic cones, say, 15 years ago: I would have made a fortune by now.

One reason for driving on Sundays or Bank Holidays is that there are usually somewhat fewer large lorries, as Dad would have called them pantechnicons, on the motorway. It’s not the lorries themselves that are the problem, but their drivers, who will insist on overtaking each other v-e-r-y s-l-o-w-l-y, blocking the middle lane and causing knots of traffic in the flow behind them. Apart from the delay and congestion thus caused, it does nothing for other drivers’ tempers.

There did, however, seem today to be an unusually large number of grey vans on the road. “White van man” is a well-recognised sub-species, rushing the dubious instruments of his dubious trade around with him in his anonymous vehicle, cursing the VAT man and clamouring for Brexit. Perhaps he has decided that now would be a good time to cultivate a lower profile. Anyway, these grey vans were up to their usual tricks, weaving through the traffic, constantly switching from lane to lane and sitting peremptorily on your tail if you had the temerity to obstruct their progress.

We also noticed one blue van, but I don’t think it will catch on.

——————-

Russians and Americans

8 April 2017

No, not a piece about international relations which are going through a sticky patch at the moment, nor a reflection on the 1984 album by folk-rock musician Al Stewart [John: ugh]. John has been staying with me in Oxted for the last couple of days, and on Thursday we went to see two exhibitions at the Royal Academy: America after the Fall, which features American paintings from the 1930s, and Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932. Actually John has been to see several other exhibitions too, but he will have to write about them for himself. I am more selective, but these two sounded interesting. And they were.

The Russian exhibition is quite large and includes film and ceramics as well as paintings. It also provides a useful sketch of the historical backdrop, about which I have to say my knowledge was only sketchy. After the 1917 Revolution in which the Bolsheviks were triumphant, there was a period of relative openness in the arts. Indeed many artists and other intellectuals initially welcomed the Revolution. Propaganda to win the support of the masses to the Revolutionary cause was important, but other forms of artistic endeavour were not suppressed until Stalin’s clampdown in 1932, after which Soviet realism was the only approved style.

The exhibition covers this period, and is notable for the very wide range of styles being displayed: everything from Brodsky’s traditional portraiture, which is actually very good, to the modernism of Kandinsky and Malevich, two figures of international reputation who feature in my favourite (but basic) arts reference books. I did notice in the RA bookshop afterwards a volume entitled Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That, which might as well have been written in response to Kandinsky; but I do in fact rather like his paintings, or at least those in this show. With Kandinsky I was able to see connections to some of the work of Joan Miró which John and I saw in an exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2011, though who influenced whom, or whether they developed on parallel but separate lines, I couldn’t say. There are also some early paintings by Marc Chagall, but as he was an early emigré he does not feature strongly in this exhibition.

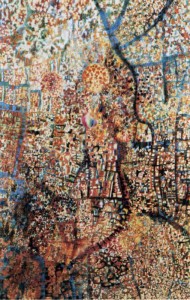

Apart from the range of styles it was fascinating to see the work of artists of whom John and I had never heard, among whom three stood out: Alexander Deineka, Pavel Filonov and Lyubov Popova. Deineka seems to have specialised in large scale works combining realistic quasi-propaganda content with almost abstract geometric figures. There are three big paintings by him on view: Textile Workers, Construction of New Workshops, and The Defence of Petrograd.

The show includes several posters by Popova which I found rather uninteresting, but also a couple of complex abstract paintings, rather reminiscent of Malevich I thought.

However, so far as I was concerned the real revelation of the show was Filonov. With several of the painters exhibited it was possible to see an evolution of style, but Filonov takes this to extremes. Could you imagine that these two paintings were by the same hand? I think the Tractor Shop may be my favourite painting in the whole show, partly because it reminds me in a curious way of my favourite paining of all, Henri Rousseau’s Surprised! Like Rousseau, Filonov uses a restricted colour palette and finds a remarkable variety of shades within it; like Rousseau he fills his picture with detail; like Rousseau he uses a perspective that is slightly “off.” Mind you, I am not sure that Filonov would altogether appreciate the comparison.

In any event, though, of all the unfamiliar artists on display Filonov is the one who most deserves to make his way into the modern art textbooks. Of course, his work and that of many others now on display was ruthlessly suppressed in Stalin’s time and is only now coming back to light, so it is not surprising that he and others have been overlooked. The exhibition notes several paintings that were hidden from the Soviet authorities and clearly there are tales that could be told about their preservation.

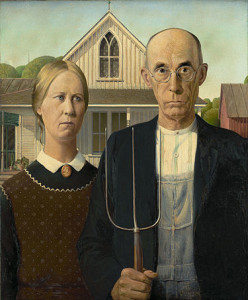

The American exhibition is smaller and, I have to say, rather less interesting. Whereas with the Russians there is a clear sense of exploration of subject and technique, the American artists on display mostly seem more conservative or, when they attempt more adventurous techniques, more effortful and contrived. This may be something to do with the range and selection of the paintings on display: there is for instance only one by Georgia O’Keefe and not, I think one of her best.

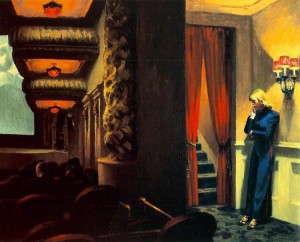

But I was pleased to see one iconic painting by Grant Wood and another which, though not so familiar, I though equally striking. There are several other of his works in the show, though none, I think, so good as these.

Edmund Hopper also features, including one of his best known paintings. But generally the pictures in this exhibition seemed to both John and me to be more workmanlike than really inspired.

It is also, of course, possible that art fatigue had crept in by this stage. We spent the best part of two hours at the Russian exhibition, had a brief lunch followed by a browse in Waterstone’s bookshop, then returned to the RA for the Americans. That’s quite a lot of standing around and looking at stuff. The American exhibition was also more crowded, which isn’t really conducive to the best appreciation of whatever is on display. I bought both the catalogues for further perusal and they may serve to show that I have not given the Americans enough credit.

——————–

The new season

7 April 2017

Amazingly, the new County Championship cricket season starts today. It’s not Easter yet, and the new edition of Wisden had not yet appeared in Waterstone’s bookshop when I looked for it yesterday. But, over the last decade or so, the Championship has been moving earlier (and later) in the year to make room for the more lucrative fifty-over and twenty-over competitions during the high summer when more people, especially families, may be enticed to attend.

The risk in April is of rain, wind and snow (though I do remember an occasion, some years ago, when a Derbyshire vs Lancashire county match was snowed off, at Buxton, in June). But in fact today it is bright and sunny here in Oxted, as it has been for the past several days, and it does actually feel like cricketing weather. The cricket square is in fine trim too. When I walked across the ground a couple of days ago, one of the pitches had already been closely mown, so perhaps Oxted will be playing over the Easter weekend.

The Guardian newspaper and the cricinfo website have been busy with their predictions for the new county season. The general consensus, including among the bloggers who contribute “below the line” on the Guardian website, is that my county, Lancashire, will struggle this season to maintain their place in the First Division of the Championship, and I am bound to say I agree with that. But we are not without hope.

So far as international cricket is concerned, the early part of the summer will be taken up with one-day (fifty-over) cricket, as the Champions Trophy is being held in England, and so the Test match season in England will not start until July. By that time the County Championship will already be half over, and this is good news for Lancashire, because our two best players, Haseeb Hameed and James Anderson, will not be needed for England’s one-day team, although they are both likely to play in the Tests. So they will provide welcome reinforcement for the county during the first half of the Championship, and that may just be enough to ensure survival in the First Division.

It is even more difficult than usual to predict what may happen in the Championship this year because of an influx of Kolpak players, mostly from South Africa. From Wikipedia: “…a European Court of Justice ruling, handed down on 8 May 2003 in favour of Maroš Kolpak, a Slovak handball player… declared that citizens of countries which have signed European Union Association Agreements have the same right to freedom of work and movement within the EU as EU citizens.” South Africa is one such country, and so South African players have an absolute right to play in the County Championship without restriction.

There is not much money in South African cricket for its players, and its Test team is selected using a quota system which requires that a certain proportion of the players must come from non-white backgrounds. So, ever since the Kolpak ruling, there has been a steady trickle of South African players seeking to make their fortune in the English county game, especially players from white backgrounds who believe their chances of playing for South Africa to be limited. However, the prospect of the UK leaving the EU so the Kolpak rule ceases to apply has increased that trickle into, if not a flood, at least a substantial flow.

Not every team in the First Division has taken advantage, but Lancashire and two of our likely rivals for relegation, Hampshire and Essex, have done so. We (and others) have also taken advantage of the long-standing County Championship rule which allows every team to include one (non-Kolpak) overseas player. It used to be the case that these imports were outstanding Test stars, several of whom stayed with their county sides for many years: Lancashire benefited from the services of (among others) Farokh Engineer, Clive Lloyd and Wasim Akram under this rule. But in recent years most imports have been on much shorter contracts and have not built such strong links with their individual counties.

Lancashire’s Kolpaks this year are the South African wicketkeeper batsman Dane Vilas and the veteran West Indies batsman Shiv Chanderpaul, and our overseas player is another South African, Ryan McLaren, who was previously with Hampshire. Chanderpaul has played with several counties in his time, including Durham, Derbyshire and Warwickshire and a previous stint with Lancashire. He is 42 years old now and will not improve the fielding, but he has immense stickability as a batsman and will certainly strengthen our middle order, which needs it.

Vilas is an excellent recruit and there is a chance he may stay with Lancashire for the long term, since for South Africa Quinton de Kock is the settled first-choice batsman-wicketkeeper and they do not need another. During England’s last tour of South Africa we saw a little of Vilas, who played in one Test: he looked a class act with both bat and gloves. He probably won’t keep wicket for Lancashire, as that position is taken by Alex Davies, but he will be more than useful as a back-up and his batting should be valuable.

The reasons why McLaren has been recruited are less clear. He is a useful all-rounder, a middle-order batsman and medium pace bowler, but though he has played Tests he is not of top international calibre, and Lancashire have other home-grown players on their staff, notably Jordan Clark, who offer the same mix of skills. McLaren will however offer some experience in what otherwise looks a relatively youthful home-grown squad, especially after Anderson leaves for England in mid-summer, and will provide further ballast in the middle order.

The general view of the pundits elsewhere is that the First Division will divide into two groups of four: Middlesex, Yorkshire, Surrey and Somerset competing for the title, while Essex, Hampshire, Lancashire and Warwickshire fight to avoid relegation. My own prediction is that Middlesex will win the title again. They are not likely to suffer too much from England call-ups and they are well-balanced in batting and bowling. Surrey will press them close but I do not think their bowling will be as penetrative as Middlesex. Yorkshire will, I think, suffer from an ageing seam attack who may struggle to remain fit, though their batting still looks strong and will be reinforced by the Australian Test player Peter Handscomb. I can’t help feeling that Somerset’s golden year last year, when the left-arm spinner Jack Leach benefited from friendly Taunton wickets, is unlikely to be repeated: their batting is reliant on Marcus Trescothick and James Hildreth, while Tom Abell may struggle to maintain his batting form while leading the side.

As for Lancashire’s rivals for relegation, I think Hampshire’s South African Kolpak signing Kyle Abbott may well be the Championship’s bowler of the year. He is an outstanding Test-quality bowler who has however retired from international cricket, and who has a method well suited to the English game. Hampshire may still struggle for runs, but if Abbott stays fit they should be all right. On the other hand, I think Warwickshire may struggle badly. They have not recruited during the winter. Their batting looks very dependent on Jonathan Trott, who will no doubt make plenty of runs, and Ian Bell, who may not; and their bowling unit, like Yorkshire’s, is ageing with no obvious replacements lined up.

That leaves Lancashire and Essex who, as luck would have it, play one another over the next four days at Chelmsford. If I did not already have theatre trips with John booked for today (Friday) and tomorrow, and a planned drive north together on Sunday, I would have been strongly tempted to make the trek to Chelmsford to watch. The outcome of the match may well be a token of the season ahead. If Lancashire win, I shall be more sanguine about our prospects; but if we lose, there may well be a long, hard season ahead. When Hameed and Anderson depart for England, our batting will be friable (despite Chanderpaul) and our bowling lacking penetration. We need to get those Championship points in the bank.

——————–

Twelfth Night (and a bit of Ado)

4 April 2017

Over the last few years there has been an upsurge in principal Shakespearean roles being played by women: most notably Glenda Jackson as King Lear at the Old Vic, but also Maxine Peake as Hamlet at the Royal Exchange in Manchester, and an entire trilogy of plays (Julius Caesar, Henry IV, The Tempest) at the Donmar directed by Phyllida Lloyd and led by one of my favourite modern actors, Harriet Walter.

I was tempted to see Jackson who, the reviews agree, was magnificent. But Lear has never been a favourite play of mine, as I always lack sympathy for the King who brings his troubles on himself, and by all reports this was, apart from Jackson herself, a dire production which I did well to miss. Peake in Hamlet, a play which I like better but have seen several times recently (notably Rory Kinnear at the National Theatre – excellent), was less of a temptation.

As for Harriet Walter, I’d happily go to see her in almost any play. She was Cleopatra, with Patrick Stewart as Antony, in one of the finest Shakespeares I have ever seen. But unless you are a member, or prepared to queue from early in the morning, it’s almost impossible to get tickets for the Donmar these days. And alas, though Lloyd’s productions went to New York, they were not transferred to our own West End. So I missed out.

There’s nothing wrong in principle with female actors playing male Shakespearean roles, certainly not if they are as good as Jackson or Walter. However, the latest National Theatre production of Twelfth Night, which I saw last week with my friends Michelle and Andy, goes one further by not only casting Tamsin Greig but also changing the gender of her character: she is not Malvolio, but Malvolia, thus adding another twist to a play in which there is already one female character (Viola/”Cesario”) masquerading as a man.

Greig was excellent, as you would expect – she is a fine actor, especially in comedy roles. A few years ago John and I saw her at the RSC as Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, where she pretty consistently got the better of Jasper Britton as Benedick. That was a good production too, its highlight being the eavesdropping scene which predictably brought the house down. The letter scene in Twelfth Night has a very similar feel, though here it is Malvolia who is being spied upon, whereas it is Beatrice who does the spying; and Greig made the most of it without overstepping the mark.

Now I think about it, there is another similarity between Much Ado and Twelfth Night, in how Shakespeare suddenly changes the tone: Beatrice’s instruction to Benedick “Kill Claudio!” which is really hard to bring off without breaking the spell, and Malvolio’s final words “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you!” which introduce an unexpected sour note into the final scene. Whenever I have seen Twelfth Night in the past, I’ve always felt that Malvolio gets a raw deal. To be sure he deserves mockery, but his incarceration goes well beyond a joke.

I’ve seen Much Ado many times and “Kill Claudio!” is a crucial moment, since Beatrice’s passionate anger has to be real, and therefore the threat to Claudio has to be real, and thus the play really does swing from comedy to melodrama in that instant. A few years ago John and I saw a production by Iqbal Khan at the RSC in which the sequence of events in the play was subtly altered so the sense of danger was short-lived. The play’s momentum was fatally weakened. By contrast, the film production by Joss Whedon, with the excellent Amy Acker as Beatrice, gets this moment spot on. Whedon’s production is modern-dress and implies an American Mafia background, in which the juxtaposition of high comedy and melodramatic revenge makes more sense than usual, especially if you have ever seen The Sopranos on TV.

So, what is going on in Twelfth Night? This latest production, I suspect unintentionally, suggested an answer. The theatre programme has a couple of rather turgid essays about the play’s sexual politics, as if making Malvolio into a woman and thus adding lesbian passion (Malvolia’s, for Olivia) adds another layer to Shakespeare’s intended confusion of the genders. But as played by Greig, it is not Olivia she has fallen for, but the power that she represents. We see that Malvolia is a petty tyrant within the household, and like other tyrants she wishes to extend her reach. Her tyranny reveals itself in a highly Puritan attitude to the merrymaking of Toby Belch and Andrew Aguecheek. So when Malvolia gets her comeuppance it is not just personal: it is a rejection of the Puritanism which wished to suppress the theatre, and Shakespeare expected his playgoing audience to join him in celebrating the Puritan’s discomfiture.

I have never seen this subtext so clearly brought out. It makes a lot more sense than a sudden outbreak of homosexual longing. When Shakespeare makes Orsino feel drawn towards “Cesario,” it is done for laughs (which were of course compounded at the time by all the actors being male), not as an indicator of latent homosexuality, and all the modern interpretations cannot make it otherwise.

Tamsin Greig is the star, but in general the production is well acted and directed. The quality of verse speaking is not generally as high as at the RSC, but quite natural and easy to follow. Of the other actors only Tamara Lawrence as Viola/Cesario seems underpowered. I suspect that she is a beneficiary of a policy to cast more black actors, which again is a worthy objective so long as they are up to their parts. I particularly liked Doon Mackichan as Feste, another woman successfully playing what is traditionally a man’s role: she took off a bit of the edge in Feste’s words, and sang her two songs (Come away, Death and For the rain it raineth every day) with a fine clear voice and tone.

As in the National’s previous Shakespeare, As You Like It with Rosalie Craig, the music is very good. The score for As You Like It was composed by my former college-mate, Orlando Gough, who was notionally a maths undergraduate but in fact seems to have spent most of his time at Corpus on music (and cricket – he was a fine batsman), and has subsequently made himself a career as a composer. Twelfth Night’s composer is Michael Bruce and his songs are equally good. Many composers have tried their hands at setting Shakespeare’s songs to music, but it is a surprisingly difficult thing to do: many stage productions resort to faux-Tudor modes and instruments, which just sound thin and unconvincing. It is to Gough’s and Bruce’s credit that they have composed fresh music that sounds apt without being in any way pastiche.

The National Theatre’s two main auditoriums offer directors a range of set-building and other technical resources, which create both an opportunity and a risk, since an over-busy design can ruin a production. A much-praised Much Ado from a decade ago, with Simon Russell Beale and Zoe Wanamaker, seemed to me to fall into this trap: the set was distracting and interfered with the action. Last year’s As You Like It, beginning improbably in a modern office complete with desks and screens which were then hauled up to the ceiling to suggest the forest canopy in Arden, flirted with the same danger. On the other hand, Rory Kinnear’s Hamlet, with its sliding panel screens, evoked a court filled with paranoia and eavesdropping extremely well.

Fortunately, Twelfth Night is nearer this end of the spectrum. It makes good use of the revolve, with two panels each shaped like half a ziggurat (stepped pyramid) that can be independently shifted to represent the play’s rapidly-changing scenes. For a non-Shakespearean audience the set brought clarity (even if it wobbled a bit) and thus served its purpose.

Michelle and Andy do not quite share John’s or my enthusiasm for the theatre in general or Shakespeare in particular, but they had a good time at this show. So, to coin a phrase, All’s Well That Ends Well.

——————–

Board Games

2 April 2017

The very first board game I can remember is Snakes & Ladders, which I must have played many times with Mum or Dad when I was no more than four or five years old. (I could count and do sums long before I went to school.) It is a traditional game, of course, but I can still see in my mind’s eye the board which we used. There were 10 rows of 10 squares you had to traverse. At the top was an evil snake which led right down to the third row, and if you got past that one, there was a little snake – I think it was on square 99 – which took you back just a few spaces so you had to pass the big, dangerous one all over again. I remember the triumph of winning, the glee when an opponent went down the long snake, and the frustration when it happened to me.

We also had a copy of Sorry!, a game which is amazingly more than 80 years old and still being published today. Sorry! is very similar to Ludo, as you have four counters which you have to move around the board from start to Home, and if you land on the same square as an opponent you send them back to the start. (Sorry!) However, movement in Sorry! is governed by the turn of cards, not by the roll of dice, and some of the cards have special abilities. I remember that when you started a new counter you really wanted a 4, as that moved you backwards and enabled you to bypass almost the entire board. Our Sorry! set became more and more tattered and no doubt Mum eventually just threw it away when we no longer seemed interested.

As I grew older we built up a much-prized collection of Waddington’s (and a few others’) board games, which lived in a cupboard and were brought out when friends came round for tea. I think the family favourite was Careers, in which you set a secret target for yourself (measured in wealth, fame and happiness) and moved your piece around the board trying to achieve it, following different tracks which represented different occupations. Going to sea was good for happiness, and flying to the Moon for fame; I don’t now remember what the other six possible careers were, and I believe that in any case different editions of the game used different career paths. Movement was governed by the roll of a die, though you were able to choose whether to embark on a particular career, and it was possible to collect cards which allowed you to modify your die rolls to achieve better outcomes. So there was at least the illusion of strategy.

My personal favourite was probably Buccaneer, one of the very few games of this era in which each turn’s movement was not randomly determined by cards or dice. You were in control of a pirate ship, and your aim was to collect treasures. Your crew was represented by black and red cards: the total value of your cards determined how far you could move, but your fighting strength was the difference in value between red and black, so it was in your interest to concentrate on one colour or the other. You could intercept other players’ ships, fight them and try to steal their treasure; trade for crew or treasure at various ports; or head for Treasure Island and turn a card, hoping to gain some treasure or at least a few new crew.

We also had Kimbo, another variant on the Ludo theme, this one played on a square grid with starting positions in the corners and the Home area at the centre. Kimbo’s special feature was that each turn you moved one of your fences, which fitted neatly into slots along the sides of the grid squares. Counters moved in straight lines except when they reached a fence. So there was some (a little!) skill in moving your fences to best effect.

My friend Paul Power particularly enjoyed another game, Spy Ring, in which you wandered round an unnamed city (die rolls governing movement, again) and searched embassies for tokens in your own colour. When you found one, you drew two secrets cards, and from these cards you were able to build up passwords with which, eventually, you could win. There’s quite a good dscription and review on the BoardGameGeek website: https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/374489/spy-ring-review-contents-rules-and-gameplay-pics.

My friend Paul Power particularly enjoyed another game, Spy Ring, in which you wandered round an unnamed city (die rolls governing movement, again) and searched embassies for tokens in your own colour. When you found one, you drew two secrets cards, and from these cards you were able to build up passwords with which, eventually, you could win. There’s quite a good dscription and review on the BoardGameGeek website: https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/374489/spy-ring-review-contents-rules-and-gameplay-pics.

Our collection also included a few games which were no-one’s favourite, and rarely played: Monopoly (of course), Risk and Cluedo. Board gamers owe Monopoly’s first publisher, Charles Darrow, a vote of thanks for building the groundwork of our hobby, but really it is a horrible game which takes forever, is far more dependent on luck than skill, and eliminates players along the way, an anti-social feature that better games mostly avoid. I don’t believe we ever finished a single game. Risk has very similar problems, and as it is a wargame, albeit of a grossly simplistic kind, it involves direct player vs player conflict, which with children and families is always liable to escalate beyond the board in one way or another. As for Cluedo, though it has memorable characters (who has not heard of Colonel Mustard?), the game just seems to me to be plain dull and its continued popularity a great mystery.

When I went up to Oxford, the board games stayed in their cupboard and I think were quietly forgotten. Some of my Oxford friends played Diplomacy, but I stayed away. The essence of Diplomacy is not the movement of pieces on the board, but the agreements reached privately between the players which they are entirely free to break any time it suits them. The rules actually stipulate an interval between turns to allow for negotiations to take place. I know of at least one lasting feud which was initiated by a game of Diplomacy and there were other broken friendships and hurts caused by the game. Many board games can go this way if the players are so minded, but Diplomacy is the only one I know where the whole essence of the game is broken promises.

The one game which I did play at Oxford was chess. I had played a little at school, especially in the sixth form, and once or twice for the school team – for some reason I remember going with the team to Ormskirk, though I have absolutely no memory of what happened, good or bad. But I had never studied the game or attempted to develop my ability to play. At Oxford, the college chess team was captained by Chris Jones, who lit a faint spark of interest in me. Chris lent me an encyclopedia of chess openings which extended my horizons considerably, and I still have a few chess books which I purchased for myself at around this time. I remember, too, that I followed closely the great world championship match in 1972 between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer: I went so far as to arrange daily deliveries of a newspaper to my parents’ Lake District cottage where I spent the summer holiday, specifically so I could keep up with progress in the match.

But that encyclopedia marked the beginning of the end of my serious interest in the game. I gradually realised that to excel at modern chess you need to learn a vast repertoire of opening theory, sometimes 15 or 20 moves deep, before the opportunity arises for fresh strategy. Obviously, at the level at which I was playing, the demands are less, but it is still the case that the player with the greater memory for opening lines of play will have the advantage. That’s great if chess is your obsession, but it was never mine. When I played my nephew Andrew at chess in 2010, it was my first game for something like 35 years.

The hobby of board games for adults has never quite gone away, but it received a great boost in the 1980s with the publication of first a handful, then a flood of new games, especially in the USA and Germany. They are characterised by ingenious design and high quality production, with the role of luck minimised and good play rewarded. Not surprisingly they have caught my interest and I now have a good collection of games which I play with friends. I started this blog intending to write about one of the latest, but thought a few preliminary words might be in order. I guess it will have to wait for another time.