Screen adaptations of John Le Carré

24 January 2018

Soon after I bought my beautiful new television, I took out a subscription to Amazon’s Lovefilm service, which supplied DVDs on loan. It was a slick, professional service, which Georgina had recommended to me, and for a while I made good use of it. Among other things, it was from Lovefilm that I rented Elementary and Sherlock, which I wrote about in a previous blog (13 March 2017).

Lovefilm has now closed down, probably because Amazon was trying to clear the field for its new video streaming service, Amazon Prime. But if that was the reason, it may have misfired, as I, and many other former Lovefilm users, have switched my allegiance to a different DVD rental company, Cinema Paradiso. They used to specialise in art-house and foreign movies, the kind that John likes, but have expanded their service to meet the new demand. I don’t think they yet have as wide-ranging a collection as Lovefilm, but it is quite enough to be getting on with.

Lovefilm has now closed down, probably because Amazon was trying to clear the field for its new video streaming service, Amazon Prime. But if that was the reason, it may have misfired, as I, and many other former Lovefilm users, have switched my allegiance to a different DVD rental company, Cinema Paradiso. They used to specialise in art-house and foreign movies, the kind that John likes, but have expanded their service to meet the new demand. I don’t think they yet have as wide-ranging a collection as Lovefilm, but it is quite enough to be getting on with.

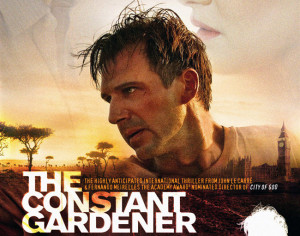

One of the first films I borrowed from Cinema Paradiso was The Constant Gardener, which was originally released in 2005. At that time I was paying less attention to cinema; my main focus was on work and family. I am very glad to have caught up with it, however belatedly.

One of the first films I borrowed from Cinema Paradiso was The Constant Gardener, which was originally released in 2005. At that time I was paying less attention to cinema; my main focus was on work and family. I am very glad to have caught up with it, however belatedly.

The film is closely based on John Le Carré’s novel of the same name, and follows Justin Quayle (played by Ralph Fiennes), a British diplomat in Kenya, as he tries to solve the murder of his wife Tessa (Rachel Weisz). The story of their developing relationship is told in a series of flashbacks. The location photography in Africa is stunning and the scenes of life in an African city, which presumably were filmed live and unrehearsed, are mesmerisingly evocative.

But it is the story and the lead performances which most caught my attention. My first encounter with Le Carré was his Cold War thrillers, especially Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy which was memorably dramatised by the BBC with the peerless Alec Guinness as George Smiley alongside several other top-notch character actors. The pervasive atmosphere in those stories is disillusioned and claustrophobic. We are told that momentous issues are at stake, but the world we see is closed in on itself and remote from normal life.

After the Cold War, Le Carré moved on. The Constant Gardener has a larger canvas, but also a greater emotional heft. The villains of the story are pharmaceutical companies who carry out field trials of new drugs in Africa under cover of humanitarian work at the cost of a few bribes, and who ruthlessly protect themselves when threatened. Le Carré pulls no punches. If you doubt him, have a look at the real-life story of Pfizer’s trials of a new antibiotic: http://bit.ly/1P2LsHq. He also condemns the British officials who turn a blind eye in pursuit of British interests (ie money) abroad.

After the Cold War, Le Carré moved on. The Constant Gardener has a larger canvas, but also a greater emotional heft. The villains of the story are pharmaceutical companies who carry out field trials of new drugs in Africa under cover of humanitarian work at the cost of a few bribes, and who ruthlessly protect themselves when threatened. Le Carré pulls no punches. If you doubt him, have a look at the real-life story of Pfizer’s trials of a new antibiotic: http://bit.ly/1P2LsHq. He also condemns the British officials who turn a blind eye in pursuit of British interests (ie money) abroad.

It was Rachel Weisz who garnered the greatest plaudits for the film, being nominated for Best Actress at the Oscars and the BAFTAs. She gives a fine sympathetic performance as Tessa, revealing her open heartedness (the scenes when she mingles with the city crowds are revealing of both Tessa’s and Weisz’s personality) and her fierceness in pursuit of her cause. But it was Ralph Fiennes, as Justin, who most caught my eye. Justin starts out as a caricature British diplomat, self-effacing, apologetic, buttoned-up, rather unlike Fiennes’s more usual persona. But as the film proceeds we see his journey as he follows in Tessa’s path: resolution, anger, despair, commitment, eventually understanding and acceptance.

It was Rachel Weisz who garnered the greatest plaudits for the film, being nominated for Best Actress at the Oscars and the BAFTAs. She gives a fine sympathetic performance as Tessa, revealing her open heartedness (the scenes when she mingles with the city crowds are revealing of both Tessa’s and Weisz’s personality) and her fierceness in pursuit of her cause. But it was Ralph Fiennes, as Justin, who most caught my eye. Justin starts out as a caricature British diplomat, self-effacing, apologetic, buttoned-up, rather unlike Fiennes’s more usual persona. But as the film proceeds we see his journey as he follows in Tessa’s path: resolution, anger, despair, commitment, eventually understanding and acceptance.

These two performances dominate the film, but I was amused to notice Richard McCabe (see my blog Imperium from a few days ago) as Tessa’s cousin Arthur Hammond. It is he who is Justin’s trusted contact in London and who eventually exposes the conspiracy in a very public way. I also recognised Bill Nighy as the corrupt senior British official, Sir Bernard Pellegrin, whom Hammond denounces; but it is a classic Nighy performance, which he might easily have delivered in his sleep. Really it is Fiennes, Reisz, the cinematographer and Le Carré himself who carry the film.

These two performances dominate the film, but I was amused to notice Richard McCabe (see my blog Imperium from a few days ago) as Tessa’s cousin Arthur Hammond. It is he who is Justin’s trusted contact in London and who eventually exposes the conspiracy in a very public way. I also recognised Bill Nighy as the corrupt senior British official, Sir Bernard Pellegrin, whom Hammond denounces; but it is a classic Nighy performance, which he might easily have delivered in his sleep. Really it is Fiennes, Reisz, the cinematographer and Le Carré himself who carry the film.

I was led to seek out The Constant Gardener after watching another Le Carré adaptation, The Night Manager, which was produced as a six-part series by the BBC in 2016, and which became my first ever loan from Lovefilm. I enjoyed it so much that I have just watched it right through for a second time, using a video streaming service which I am trying out.

I was led to seek out The Constant Gardener after watching another Le Carré adaptation, The Night Manager, which was produced as a six-part series by the BBC in 2016, and which became my first ever loan from Lovefilm. I enjoyed it so much that I have just watched it right through for a second time, using a video streaming service which I am trying out.

Probably most of my readers, even in Australia, will have seen The Night Manager for themselves, so I need not re-tell the story here. Le Carré’s novel was first published in 1993, and the BBC made several changes of detail, to make it more acceptable for television audiences and to bring it up to date. Most obviously the ending is changed so the villain gets his due, and the location is changed to the Middle East. Le Carré was by all accounts initially sceptical of the changes, but was won over by the quality of the screenplay (by David Farr) and the production. Farr is well known as a writer and director for theatre as well as film, and the writing is certainly well above the usual standards of hack TV.

The show is formidably well cast. Hugh Laurie, a surprising choice, is brilliant as the arms dealer and principal villain Richard Roper: he shows us the seductive glamour and suavity, then the tough heartlessness, but only at the end is all veneer stripped aside and we see the egotism and contempt for others. Laurie is a far better actor than anyone who had seen him in Blackadder or Jeeves & Wooster, or even as the irascible doctor in House, might have realised; credit to the casting director who spotted his potential. In the polar opposite role, Olivia Colman is no less convincing as the unglamorous but utterly dedicated arms control officer Angela Burr. Her pregnancy, which becomes increasingly visible as the story proceeds, was real, and was worked very effectively into the script, increasing her apparent vulnerability. But we can see she is a tough, uncompromising lady, not above a little moral blackmail to get what she wants, whose commitment has earned the unquestioning loyalty of the team she leads. Tom Hiddleston is a perfect fit for Jonathan Pine, the ex-soldier who infiltrates Roper’s organisation and brings about his downfall. As others have said, he would make an excellent Bond: strong, silent, enigmatic. There’s a lot of subtle detail in his performance which makes him credible both to Roper and to the audience.

The two other principal roles are equally well played but require, perhaps, a little less depth. Tom Hollander got a lot of praise from the critics as Roper’s enforcer Corkoran, but by comparison with the others I thought him just a little obvious. I suppose it is difficult to bring too much subtlety to a character who is ostentatiously gay and drinks too much. By contrast the critics tended to overlook Elizabeth Debicki, who plays Roper’s mistress Jed, but she manages her gradual slide from glamour to unease to fear very convincingly.

For a television series the production values are exceptionally high, with location filming in Mallorca, Switzerland and Morocco as well as Devon and London. Richard Roper’s opulent hilltop villa and the refugee and army encampments, supposedly in Turkey, are particularly impressive. There are also some formidable pyrotechnics. Le Carré generally features more menace and casual violence than big explosions, but when these come, especially when you see the final episode for the first time, they are very effective.

One big advantage enjoyed by the series is that, in six hour-long episodes, it has the space to tell quite a complex story in full. Two previous attempts had been made, and failed, to reduce it to the length of a feature film. As with any successful series there have been calls for a sequel, but I hope they will be resisted. Instead, I would like to see more small screen adaptations of Le Carré’s novels, allowing their complex plots and themes time to breathe, but with the same high quality production as The Night Manager – which has shown how it can be done.

——————–

Terraforming Mars

23 January 2018

Two weekends ago my friends Trevor, Tom and Mark came to Oxted for one of our regular games afternoons, and played a new game which Trevor had brought with him: Terraforming Mars. I have previously avoided writing about individual games, for fear of wearying my readers. But TM is such a good game that I will make an exception. Please, bear with me. You may even learn something.

Two weekends ago my friends Trevor, Tom and Mark came to Oxted for one of our regular games afternoons, and played a new game which Trevor had brought with him: Terraforming Mars. I have previously avoided writing about individual games, for fear of wearying my readers. But TM is such a good game that I will make an exception. Please, bear with me. You may even learn something.

Terraforming is the name given to a hypothetical process of large-scale engineering whose purpose is to make the surface of a planet or moon habitable by humans without the need for protective gear. It is a real scientific concept: see, for instance, http://bit.ly/1HTk26e (Wikipedia) or http://bit.ly/2mYpsaK (Universe Today). However, you are more likely to come across it in science fiction. In particular, the terraforming of Mars is central to Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy which I mentioned in my blog on 28 November last.

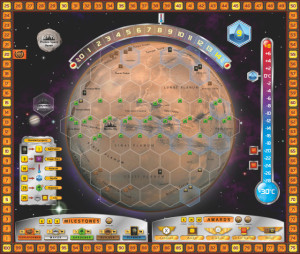

In TM, each player represents a mega-corporation which is working with the others to complete the terraforming of Mars. The players must collectively raise the surface temperature, add oxygen to the atmosphere and place 9% of the planet’s surface under water. When these targets have been completed, the game ends.

Apart from scoring tracks, the game board consists of a more or less accurate map of one face of Mars, with poles at top and bottom. The map is marked out with a hexagonal grid, 100 hexagons in total, and the game includes a set of tiles which are placed on the map as the game progresses, to represent the development of cities, oceans and greenery. Oceans can only be placed in low-lying areas which are clearly marked on the board.

Apart from scoring tracks, the game board consists of a more or less accurate map of one face of Mars, with poles at top and bottom. The map is marked out with a hexagonal grid, 100 hexagons in total, and the game includes a set of tiles which are placed on the map as the game progresses, to represent the development of cities, oceans and greenery. Oceans can only be placed in low-lying areas which are clearly marked on the board.

Players can draw on a variety of resources to assist their efforts: money, iron, titanium (for space projects), plants, energy and heat. They start with a basic income of money and possibly of some other resource(s), and may add to this income as the game proceeds. Each of the mega-corporations gives its player a different amount of money at the start of the game and some other unique advantage in income or costs or scoring.

The heart of the game lies in the projects which the players undertake. There is a deck of 208 cards, each of which represents a specific project or activity. The players start by drawing ten cards, and each round they will draw four more. These represent concepts for projects which their corporation may wish to follow up. They are not obliged to keep all the cards that they draw, but for each card they do keep they must pay three money. Think of this as the cost of the necessary R&D before a project can be undertaken.

On their turn they may then carry out projects by playing a card from their hand and paying its cost. More ambitious projects are, obviously, more expensive to complete. Some projects contribute directly to terraforming; some projects place tiles on the board; others add to the player’s income in one or more of the resources. “Standard” projects may also be undertaken, without playing a card, which is useful if your card draw is poor.

One reason I like the game so much is that the science behind these projects seems plausible. Thus, for instance, plants help to add oxygen to the atmosphere; but many plants can only be grown when the temperature has reached a certain level. Projects range from very small (developing specialist microbes, or mining) to massive (crashing asteroids into the planet surface). Many of the project concepts are clearly based on ideas in the Mars trilogy, such as the soletta, a large lens or solar mirror placed in orbit to amplify solar radiation. See http://bit.ly/2n8wGsD (Wikipedia).

One reason I like the game so much is that the science behind these projects seems plausible. Thus, for instance, plants help to add oxygen to the atmosphere; but many plants can only be grown when the temperature has reached a certain level. Projects range from very small (developing specialist microbes, or mining) to massive (crashing asteroids into the planet surface). Many of the project concepts are clearly based on ideas in the Mars trilogy, such as the soletta, a large lens or solar mirror placed in orbit to amplify solar radiation. See http://bit.ly/2n8wGsD (Wikipedia).

Many projects work better in combination, so each player is tempted to specialise, for instance in heat production, or in space projects. However, too much specialisation can become a dead end. Because the draw of cards is random, players cannot follow a predetermined strategy: they have to make the best of whatever options are available to them. They have also to be selective, when they draw their cards, about which ones to keep. It is simply too expensive to keep them all.

Players score points for each contribution they make towards achieving the terraforming targets, for achieving various intermediate goals, and for the tiles they have placed on the board. At the end of the game, the player with the most points wins. So there is a competitive element. You need to be aware of what other players are doing, so that you don’t duplicate their efforts and they can’t obstruct yours. But the main challenge lies in choosing and building the right projects from among the options you are given, which will be different each game, depending on which cards you draw.

After our game (which Trevor won), I ordered my own copy of TM, and have spent a couple of days this week trying it out. The rules include an excellent solo version in which the player is competing against the clock: you have just 14 rounds to achieve all the terraforming goals, that is about 75 minutes real time. So far my score is just under 50%, using three of the mega-corporations.

Modern board games are expensive. You want to get your money’s worth, so the game needs to be replayable – that is, you must not be able to determine a single optimum strategy which would take away the challenge, reducing the game to process and luck.

TM cost me £60, equivalent to lunch for two at a decent eating place, or to a good seat at the theatre. But its replayability should be high. The advantages given by the 12 different mega-corporations lead to different choices about priorities, and the draw of the cards from that massive deck ensures that each game is different. It’s not just which cards you get that makes a difference, but when you get them. Cards adding to income are useful in the early turns but of limited value later, while if you draw expensive cards early on you usually cannot to play them straight away, and have to decide whether the opportunity cost of keeping them is worthwhile.

On the BoardGameGeek website (https://boardgamegeek.com) TM is currently ranked fifth of all strategy board games, out of a total that runs into thousands. Its success has created a lot of traffic on the website, as bloggers have contributed reviews, Q&A about the rules, blow-by-blow accounts of games played and strategy suggestions. One contributor has done a detailed mathematical analysis** of probabilities and costs of projects and combinations of projects, aiming to show whether there is a specific line of play that is most likely to succeed. His conclusion? No such line exists. For a game with 208 different cards and, effectively, an unlimited number of possible combinations, that is a remarkable design achievement. TM should keep its players amused for a long time to come. Even if I never play TM again with Trevor and our group (but I am sure we will), I expect to get my money’s worth, and more, from solo games.

** There is a certain kind of board game player who just loves this kind of thing. And you can find them all on BGG.

——————–

Imperium

20 January 2018

John and I went to Stratford-on-Avon last weekend to see a new play, Imperium, at the RSC’s Swan Theatre. It tells the story of the Roman orator, lawyer and politician Cicero, who lived during the first century BC. The play is based on three novels by Robert Harris: Imperium, Lustrum and Dictator.

John and I went to Stratford-on-Avon last weekend to see a new play, Imperium, at the RSC’s Swan Theatre. It tells the story of the Roman orator, lawyer and politician Cicero, who lived during the first century BC. The play is based on three novels by Robert Harris: Imperium, Lustrum and Dictator.

The period is one of the most turbulent in ancient Roman history. The old Republic, with its elaborate systems of checks and balances and its annual elections for various public offices, was in decline, vulnerable to corruption, intimidation, vote rigging and demagoguery. The writers clearly intend us to draw parallels with modern, post-truth times, and I did notice a few sly contemporary references. But they were not forced down our throats.

Imperium occupies just under seven hours in total, divided into two parts. The first part ran from one o’clock to half past four; the second part from seven o’clock to quarter past ten. You might think this would be a bit of a marathon. But the dramatisation is by Mike Poulton, who has a track record of literary adaptations for the RSC which we have enjoyed, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Hilary Mantel’s novels about Thomas Cromwell (Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies), both of which were similarly in two parts. We thought he could be trusted; and in fact Imperium fully lives up to his previous standard.

Perhaps a bit of history will be helpful. Rome at this time did not have organised political parties like ours, but it did have two very different factions, the aristocrats (Optimates) and the people (Plebeians). The top political offices were usually filled by optimates, but the Tribunes were elected from the plebeians, and they had a veto. So Roman politics had to proceed through compromise and alliances of convenience. As a result, much-needed reform of Rome’s system of government was never carried through.

Perhaps a bit of history will be helpful. Rome at this time did not have organised political parties like ours, but it did have two very different factions, the aristocrats (Optimates) and the people (Plebeians). The top political offices were usually filled by optimates, but the Tribunes were elected from the plebeians, and they had a veto. So Roman politics had to proceed through compromise and alliances of convenience. As a result, much-needed reform of Rome’s system of government was never carried through.

Also during this period, Roman armies were rapidly annexing new provinces in Gaul, Spain and Asia Minor. The legions owed much more loyalty to their commanders than to Rome; so when legions and commanders returned home they were a political force to be reckoned with. There had already been one military dictatorship, under the successful general Sulla, earlier in the century.

Cicero was neither an optimate nor a plebeian by birth. But he was Rome’s leading orator and lawyer, a useful ally and a dangerous opponent. As a lawyer and a traditionalist, he wished to preserve the existing constitution and, therefore, the rule of the optimates. Part 1 of the play shows how he achieved and exercised power until he over-reached himself in a political trial, was humiliated and forced into exile.

Part 2 then tells how the conquering Julius Caesar returns to Rome, becomes dictator and is assassinated. Although Cicero is sympathetic to the assassins’ aims, he is not among them. The assassins fail to consolidate, and instead it is Cicero who for a while leads the traditionalist party in Rome against Antony’s faction; there is bitter enmity between them. He also tries hard to win over Caesar’s nominated heir, Octavian, to his side. But eventually Octavian allies with Antony and connives in Cicero’s assassination.

The pace of the action never flags and, as is essential for a play of this kind, the characters are all easily identified. To modern ears, compound Roman names (like Gaius Julius Caesar or Marcus Tullius Cicero) can become bewilderingly similar, but Poulton avoids the trap: it is always clear who is doing what, with whom, to whom. Moreover, so far as I can tell, everything that happens is historically accurate. This is a period which I studied at university, and I did not spot any gross errors or distortions, though I was abashed to realise how little of the detail I had remembered.

Characterisation is another matter. It would be hard to portray Caesar as anything other than the historical record tells us: a crude, cynical, capable megalomaniac. But Poulton really emphasises the dithering of Brutus and Cassius (much to Cicero’s dismay) after the assassination, and portrays Antony as a tempestuous drunkard who frightens his supporters as much as he inspires them. When Octavian comes on the scene Poulton makes Cicero treat him with disdain, calling him boy, which Octavian bears with patience. With the wisdom of hindsight we recognise the error, but it was a mistake that many Romans made at the time. By the time Cicero realises his error it is too late.

And what of Cicero himself? He is played here by Richard McCabe and it really is an astonishing performance. John and I know McCabe of old. He was a peerless Iago in an RSC production of Othello set in the British Raj, which we saw at Stratford nearly twenty years ago. It was so good, thanks particularly to McCabe and Ray Fearon (who played Othello), that we have not wanted to see the play since, for fear of disappointment and of dimming our memory.

And what of Cicero himself? He is played here by Richard McCabe and it really is an astonishing performance. John and I know McCabe of old. He was a peerless Iago in an RSC production of Othello set in the British Raj, which we saw at Stratford nearly twenty years ago. It was so good, thanks particularly to McCabe and Ray Fearon (who played Othello), that we have not wanted to see the play since, for fear of disappointment and of dimming our memory.

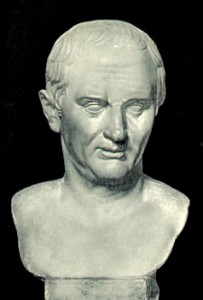

McCabe’s Cicero is equally good, though good is an inadequate description. Tour de force would be better. He completely inhabits the role. And it is a monster role, on stage for almost all of the play’s seven hours. He shows Cicero in all his moods and circumstances – shrewd but vain, brave more in word than deed, politician and philosopher, inadequate husband and adoring father, through triumph, crisis and disaster – and never strikes a false note. His delivery of Cicero’s first important legal oration, Against Verres, is spot-on for its power and impact. Later, and equally convincingly, he shows us how Cicero’s vanity and vacillation exasperate his family and friends. We know Cicero’s appearance from surviving marble busts; McCabe even manages to look like him. And he ages convincingly (the play covers a period of more than 20 years) with just the right amount of added hesitations and mannerisms while remaining true to the character.

McCabe’s Cicero is equally good, though good is an inadequate description. Tour de force would be better. He completely inhabits the role. And it is a monster role, on stage for almost all of the play’s seven hours. He shows Cicero in all his moods and circumstances – shrewd but vain, brave more in word than deed, politician and philosopher, inadequate husband and adoring father, through triumph, crisis and disaster – and never strikes a false note. His delivery of Cicero’s first important legal oration, Against Verres, is spot-on for its power and impact. Later, and equally convincingly, he shows us how Cicero’s vanity and vacillation exasperate his family and friends. We know Cicero’s appearance from surviving marble busts; McCabe even manages to look like him. And he ages convincingly (the play covers a period of more than 20 years) with just the right amount of added hesitations and mannerisms while remaining true to the character.

To set the scene and bridge gaps in the story, Poulton follows Harris in introducing as a character Cicero’s slave and secretary, later his freedman and friend, Tiro. He sometimes steps forward and addresses the audience directly, sometimes participates in the action, sometimes provides an ironic or exasperated on-stage commentary. He often knows what would be best for Cicero far better than Cicero does himself. This key role is played by Joseph Kloska, a name new to me – but I expect we shall be seeing a lot more of him in future. One critic has admired his “irrepressible wit and verve,” and that seems about right.

To set the scene and bridge gaps in the story, Poulton follows Harris in introducing as a character Cicero’s slave and secretary, later his freedman and friend, Tiro. He sometimes steps forward and addresses the audience directly, sometimes participates in the action, sometimes provides an ironic or exasperated on-stage commentary. He often knows what would be best for Cicero far better than Cicero does himself. This key role is played by Joseph Kloska, a name new to me – but I expect we shall be seeing a lot more of him in future. One critic has admired his “irrepressible wit and verve,” and that seems about right.

If I do not single out other actors by name, it is only for reasons of space. The RSC has a well-deserved reputation for consistently fine acting, even in minor roles, and Imperium lives up to that standard. The direction, by Gregory Doran, keeps things simple and clear, so that we always know where we are supposed to be. A flight of steps leads up across the back of the stage, with a Roman-styled mosaic pattern on the rear wall; and in the centre of the thrust stage a hatch is opened from time to time to represent a pool or a cistern, or to raise and lower a few more substantial props like Caesar’s bier. But for the most part the stage is bare, leaving Doran and his actors free to keep the story moving. There is one weak moment in the play, when the ghost of the recently assassinated Caesar is brought on stage. It is a Shakespearean device, but reminds us that this is not Shakespeare; it is unnecessary, and breaks the flow. The ghost calls for revenge, but we have already got the message. I really don’t know why Poulton included this scene, or why Doran acquiesced in it. But it is a minor blip in an otherwise outstanding production.

There is one weak moment in the play, when the ghost of the recently assassinated Caesar is brought on stage. It is a Shakespearean device, but reminds us that this is not Shakespeare; it is unnecessary, and breaks the flow. The ghost calls for revenge, but we have already got the message. I really don’t know why Poulton included this scene, or why Doran acquiesced in it. But it is a minor blip in an otherwise outstanding production.

——————–

Grown-up SF on the big screen

12 January 2018

Beware : major spoilers

I have liked science fiction ever since I was a boy. I started with the children’s space adventure stories by Patrick Moore and E C Eliott and later graduated to novels by Arthur C Clarke, Robert A Heinlein and John Wyndham, no doubt among many others that I no longer remember.

I have liked science fiction ever since I was a boy. I started with the children’s space adventure stories by Patrick Moore and E C Eliott and later graduated to novels by Arthur C Clarke, Robert A Heinlein and John Wyndham, no doubt among many others that I no longer remember.

I feel more ambivalent about SF in film and television. I never much cared for TV shows like Doctor Who or Star Trek because their horizons were limited by special-effects technology and budget: they simply did not match up to what I could imagine for myself. I remember walking home after I first saw Star Wars (it must have been in 1977 or 1978) in a glorious daze because for the first time I had seen on screen something which came closer to the worlds I had been imagining. A handful of other films were made with more or less exotic SF settings: Dune, Silent Running, Alien, Outland, Blade Runner. I enjoyed them all. But, perhaps because the special effects were too expensive to be routine, they were outliers.

It is only recently, since the advent of sophisticated but not-too-expensive computer generated imaging, that SF and fantasy films have started to be made in numbers and thus to build an audience. That has opened the door for producers to start to make SF films and television with grown-up themes, where the special effects are necessary but in the background, and the story can develop the big philosophical questions like identity and free will which have previously been confined to written SF. So this blog is about three grown-up SF films I have seen in the last few months: Arrival, Ex Machina and Gravity.

Arrival is directed by Dennis Villeneuve (who went on to make Blade Runner 2049) and stars Amy Adams as Louise Banks, a professor of linguistics. Twelve massive alien spacecraft suddenly appear in widely dispersed, apparently random locations around Earth. They do nothing and pose no threat apart from their very presence, but that is enough to cause global panic and arouse international hostility. Louise is enlisted by the US Army and given the task of communicating with the aliens at the one landing site in the USA.

Arrival is directed by Dennis Villeneuve (who went on to make Blade Runner 2049) and stars Amy Adams as Louise Banks, a professor of linguistics. Twelve massive alien spacecraft suddenly appear in widely dispersed, apparently random locations around Earth. They do nothing and pose no threat apart from their very presence, but that is enough to cause global panic and arouse international hostility. Louise is enlisted by the US Army and given the task of communicating with the aliens at the one landing site in the USA.

The story explores the nature of language and how it relates to the way we think. Which determines the other? As Louise’s engagement with the aliens develops, she starts to have what we initially think are dreams of a melancholy earlier period in her life when she had a child who died of a rare incurable disease on the cusp of adulthood. About half way through the movie we realise that these are not dreams, but foretellings. The aliens perceive time not as a flow but as a state, thus enabling them to see what we call the future. As Louise learns the alien language, it starts to influence how her own mind works. There is a conventional climax as Louise struggles to unravel the aliens’ message in time to avoid war, which arguably weakens the movie; but this is followed by an elegiac coda in which Louise goes on to have the child for the joy it will bring despite knowing its eventual fate. This strand in the story gives the film an emotional kick which SF in any medium often lacks.

Louise learns to communicate because she sets aside preconceptions, has no agenda and is willing to offer her trust. Amy Adams gives an outstanding performance: she captures the fear, the wonder, the insight and the determination in Louise’s character. It’s great to see a woman in the lead role in an SF film, succeeding through female qualities of empathy and co-operation where the men, all aggression and agenda, have failed.

Louise learns to communicate because she sets aside preconceptions, has no agenda and is willing to offer her trust. Amy Adams gives an outstanding performance: she captures the fear, the wonder, the insight and the determination in Louise’s character. It’s great to see a woman in the lead role in an SF film, succeeding through female qualities of empathy and co-operation where the men, all aggression and agenda, have failed.

Villeneuve creates an atmosphere of brooding strangeness, and his aliens are … well, alien: light years away from Star Trek. Special effects are otherwise limited. This film could have quite easily been made twenty years ago, though it might have had greater difficulty finding an audience. As it is, film and director were nominated for the 2017 Oscars, and Amy Adams for best actress at the Golden Globes. They didn’t win, but for a grown-up SF film to gain these nominations was in itself an achievement.

Ex Machina, directed by Alex Garland, is a very different story and type of film, yet it shares some of Arrival’s qualities. It addresses challenging philosophical issues, in this case to do with identity and intelligence, and like Arrival sustains its atmosphere throughout. The film is essentially a three-hander featuring billionaire computer scientist Nathan (played by Oscar Isaac), the humanoid robot Ava whom Nathan has created (Alicia Vikander), and a young programmer, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), whom Nathan has recruited to help test whether Ava is a true artificial intelligence.

Ex Machina, directed by Alex Garland, is a very different story and type of film, yet it shares some of Arrival’s qualities. It addresses challenging philosophical issues, in this case to do with identity and intelligence, and like Arrival sustains its atmosphere throughout. The film is essentially a three-hander featuring billionaire computer scientist Nathan (played by Oscar Isaac), the humanoid robot Ava whom Nathan has created (Alicia Vikander), and a young programmer, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), whom Nathan has recruited to help test whether Ava is a true artificial intelligence.

Of the three it is Vikander who really stands out. Somehow she has caught exactly how you might imagine an AI in a humanoid bodyshell would behave: minute delays in her responses, a certain blandness of character. And yet: is she in fact acting the role of an AI which is itself acting the role of how we imagine an AI would behave? Are these tiny giveaways in fact deceptions? Either way, this is a compelling performance, reinforced by the film’s one persistent special effect which replaces the back half of Vikander’s skull and neck with something that looks like circuitry. It’s not a cheap prosthetic as in Star Trek but CGI wizardry, impeccably sustained and wholly convincing.

The plot is full of twists and turns like a classic spy movie. Garland delivers an unsettling claustrophobic sense of paranoia throughout. The film reaches a somewhat melodramatic climax, which I am not sure was necessary, and the science is not really plausible: I refuse to believe that a single scientist, however gifted, could design and build both the hardware and software for a functioning humanoid robot. But the question of what constitutes artificial intelligence is real and under active debate in the tech community today. As Ex Machina makes clear, the Turing test is only a start. An effective test must go much more deeply into the workings of intelligence, and somehow determine whether an AI is truly self-aware or simply programmed to behave as if it was self-aware – the difference being whether it is ultimately limited by its programming. The layers of misdirection needed to complete this test are fundamental to the plot.

The plot is full of twists and turns like a classic spy movie. Garland delivers an unsettling claustrophobic sense of paranoia throughout. The film reaches a somewhat melodramatic climax, which I am not sure was necessary, and the science is not really plausible: I refuse to believe that a single scientist, however gifted, could design and build both the hardware and software for a functioning humanoid robot. But the question of what constitutes artificial intelligence is real and under active debate in the tech community today. As Ex Machina makes clear, the Turing test is only a start. An effective test must go much more deeply into the workings of intelligence, and somehow determine whether an AI is truly self-aware or simply programmed to behave as if it was self-aware – the difference being whether it is ultimately limited by its programming. The layers of misdirection needed to complete this test are fundamental to the plot.

Arrival and Ex Machina are interesting and impressive for how they give dramatic form to difficult questions at the border between science and philosophy. Gravity, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, is a very different type of film, and a more traditional one: the survival epic. It also depends a good deal more on its special effects. The film’s central figure is Dr Ryan Stone (played by Sandra Bullock), a civilian scientist on an expedition into Earth orbit which suffers sudden disaster. Eventually she is left on her own, with no radio contact, stranded in a failing space module; she has only her own wits, incomplete knowledge and an on-board manual to guide her.

Arrival and Ex Machina are interesting and impressive for how they give dramatic form to difficult questions at the border between science and philosophy. Gravity, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, is a very different type of film, and a more traditional one: the survival epic. It also depends a good deal more on its special effects. The film’s central figure is Dr Ryan Stone (played by Sandra Bullock), a civilian scientist on an expedition into Earth orbit which suffers sudden disaster. Eventually she is left on her own, with no radio contact, stranded in a failing space module; she has only her own wits, incomplete knowledge and an on-board manual to guide her.

I had not previously thought of Bullock as a serious dramatic actress. Most of her previous roles have been in romantic comedies like When You Were Sleeping (which I once saw on a long-haul flight) or Hollywood thrillers like Speed. But she performs this role, which was reportedly extremely strenuous and lonely, to the manner born. Perhaps it is because she naturally conveys the look and feel not of a hero or an athlete or a genius, but of someone ordinary, caught up in an extraordinary but realistic disaster, who has to tap resources in herself she did not know she had.

I had not previously thought of Bullock as a serious dramatic actress. Most of her previous roles have been in romantic comedies like When You Were Sleeping (which I once saw on a long-haul flight) or Hollywood thrillers like Speed. But she performs this role, which was reportedly extremely strenuous and lonely, to the manner born. Perhaps it is because she naturally conveys the look and feel not of a hero or an athlete or a genius, but of someone ordinary, caught up in an extraordinary but realistic disaster, who has to tap resources in herself she did not know she had.

Apart from Bullock, what I liked most about this film was its stark realism. It barely qualifies as science fiction at all: with a few minor quibbles, space scientists have confirmed that a cascading orbital disaster could happen in exactly this way, and that what we see on screen is a true representation of Earth orbit.

The photography is simply sensational, capturing equally the glory of Earth seen from above, the vast darkness of space and the bewlidering sensation of free fall in the close confines of a spacecraft. It is matched by the soundtrack. Disaster, when it occurs, is immediate and totally silent. I regret that I did not see Gravity on the giant IMAX screen as I had originally hoped to do, but even on my large television screen at home it was a deeply scary experience.

Cuarón won the Oscar for his direction (Bullock was nominated but did not win), and Gravity swept the board in the 2013 awards season for its cinematography and visual effects. It showed that the technology of modern cinema can be put to better use than in Star Wars or superhero movies.

——————–

——————–

Misalliance and Oslo

12 January 2018

John came down to Oxted for a few days before Christmas. I was by then already nursing the bad cold which troubled me over the holiday period, but I was well enough for the first two shows we had booked to see: Bernard Shaw’s Misalliance, at the Orange Tree theatre in Richmond, and Oslo by J T Rogers, which we saw in the West End. Unfortunately I was too unwell for the third show for which I had tickets, The Melting Pot by Israel Zangwill at the Finborough theatre, and can only hope that as it was a sell-out it may be revived at the Finborough or elsewhere in due course.

Misalliance was first produced in 1910 and published in 1914. It is set in the home of a prosperous Edwardian industrialist, Tarleton. The household’s well-ordered life is disturbed by the arrivals of an aircraft pilot and his female passenger, who crash-land in the conservatory, and an inept young cashier, who breaks into the house intent on murder but proves incapable of carrying it out. By the end of the play some uncomfortable truths have been spoken and relationships changed. But an unkind critic might say that nothing really happens except talk.

Misalliance was first produced in 1910 and published in 1914. It is set in the home of a prosperous Edwardian industrialist, Tarleton. The household’s well-ordered life is disturbed by the arrivals of an aircraft pilot and his female passenger, who crash-land in the conservatory, and an inept young cashier, who breaks into the house intent on murder but proves incapable of carrying it out. By the end of the play some uncomfortable truths have been spoken and relationships changed. But an unkind critic might say that nothing really happens except talk.

Of course Shaw liked talking. He was a radical socialist as a young man, and later became influential in the Fabian movement. He was also an internationalist, a pacifist and a passionate advocate of women’s rights. Above all, he was a provocateur, tilting at the Establishment and delighting in argument. Dad disliked him intensely, calling him “a renegade Irishman.” I used to think this was one of Dad’s prejudices, but from Shaw’s biography I learn that he was an apologist during the 1930s for both Hitler and Stalin, when Dad was growing up, so perhaps his dislike had some foundation after all.

At any rate, though Misalliance is certainly talky, it is not empty. The first half of the play delivers a not-too-fierce satire on Edwardian complacency. Characterisation was never Shaw’s strongest point; his characters tend to be two-dimensional, archetypes or caricatures or mouthpieces for any argument Shaw wishes to pursue. But when well played and directed they can still be recognisable and amusing. The standout here is Bradley, an immature young man who has somehow become engaged to Tarleton’s daughter, Hypatia (you do really wonder how that happened, but Shaw doesn’t care). When Bradley doesn’t get his own way he has tantrums, throwing himself on the floor and screaming like a baby. It’s an extreme caricature, but irresistibly funny.

After the interval, the intruders arrive and things start to change. The young cashier mouths socialist views he plainly doesn’t really understand, but is trounced in argument by Tarleton himself and humiliated by Tarleton’s son, Johnny. It’s interesting that Shaw handles the socialist so roughly and gives so many of the best lines and arguments to the capitalist Tarleton. This reminded me a good deal of the arms manufacturer Undershaft in Shaw’s better-known play Major Barbara; as there, the intent is not to persuade but to provoke. In any event the cashier turns the tables when it is revealed that his mother was a friend of Mrs Tarleton and that he may himself be Tarleton’s illegitimate son.

But it is the female passenger who really puts the cat among the pigeons. She is Lina, a Polish acrobat and adventurer. All the men in turn (except the cashier, who seems to know better) want her as wife or mistress, but she rebuffs them all in the play’s longest speech, where irony is switched off and replaced by a passionate declaration of her independence: “I am strong: I am skilful: I am brave: I am independent: I am unbought: I am all that a woman ought to be.” Misalliance is much more than just a play about women’s rights, but at this point Shaw unfeignedly nails his colours to the mast.

In his Guardian review, Michael Billington suggests that Misalliance “reveals Shaw’s irrepressible comic gift that, in many ways, anticipates Ionesco, the Goons and Monty Python.” That seems a little far-fetched to me: the line of descent, if it exists, has many intermediate steps. But Billington rightly praises the quality of the acting and, above all, the direction. Director Paul Miller disentangles the talkiness and coaxes top class performances from his actors. It’s almost invidious to pick out individuals. I particularly liked Rhys Isaac-Jones, who makes the most of his opportunities as Bentley; Pip Donaghy, wonderfully pompous as Tarleton; and Lara Rossi, in what I took to be an orange wig (I really hope she has not dyed her hair that colour), as a striking Lina. But there is not a weak link among them.

Oslo, which we saw in a theatre packed full despite the absurd West End prices, is as different from Misalliance as chalk from butterflies. It presents as drama the secret negotiations which led up to the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the PLO in 1993. Not the most obvious subject for a play, you might think; but in fact it works brilliantly. In real life the Accords were negotiated in Oslo, in secret, and facilitated by two Norwegian diplomats. The play suggests that the Norwegians proceeded by attempting to build trust and encourage communication between the negotiators as individuals before opening any dialogue of substance. We are given a lesson in recent history and also in how political logjams can be broken through openness and by seeking opportunities for mutual benefit. I doubt whether a single member of the audience failed to note the obvious contrast with Donald Trump’s megaphone diplomacy, or with the Brexit negotiations.

Oslo, which we saw in a theatre packed full despite the absurd West End prices, is as different from Misalliance as chalk from butterflies. It presents as drama the secret negotiations which led up to the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the PLO in 1993. Not the most obvious subject for a play, you might think; but in fact it works brilliantly. In real life the Accords were negotiated in Oslo, in secret, and facilitated by two Norwegian diplomats. The play suggests that the Norwegians proceeded by attempting to build trust and encourage communication between the negotiators as individuals before opening any dialogue of substance. We are given a lesson in recent history and also in how political logjams can be broken through openness and by seeking opportunities for mutual benefit. I doubt whether a single member of the audience failed to note the obvious contrast with Donald Trump’s megaphone diplomacy, or with the Brexit negotiations.

We are not shown the substance of negotiations. A double door in the back wall of the sparsely-furnished set leads to the negotiating chamber. We see the characters outside this door, guarded or hostile before the real business begins, exhausted after marathon sessions in which they know they have, despite all odds, made some progress. We see, too, how they are gradually changed from antagonists into a single group who may have differences of view but share a common purpose. They start to tease one another, to join in making fun of the Norwegian facilitators and housekeeping staff, to drink together, to tell one another jokes. What we can see, but they cannot, is how the Norwegians’ strategy is bearing fruit, and how much these men, for all their political differences, actually have in common.

The process is far from smooth. As the negotiations progress, higher-ranking representatives are drawn in on both sides, and each in turn brings a new personality to the table, demanding new levels of trust. The drama consists in part of how negotiations almost break down under this escalating pressure. Video, projected on the back wall, is also deployed to show how outside events come close to derailing the process, as one side or the other is victim to some atrocity. The cumulative effect is almost like a thriller. With part of our minds we know that the Accords will eventually be agreed and signed, yet we constantly fear that they will be derailed by some provocation or intransigence. The action is lightened by the personalities of the Norwegian facilitators, Terje (played by Toby Stephens) the irrepressible optimist who is willing to lie, to be humiliated, to do whatever it takes to keep the dialogue afloat, and Mona (Lydia Leonard) the competent one whom everyone trusts.

The process is far from smooth. As the negotiations progress, higher-ranking representatives are drawn in on both sides, and each in turn brings a new personality to the table, demanding new levels of trust. The drama consists in part of how negotiations almost break down under this escalating pressure. Video, projected on the back wall, is also deployed to show how outside events come close to derailing the process, as one side or the other is victim to some atrocity. The cumulative effect is almost like a thriller. With part of our minds we know that the Accords will eventually be agreed and signed, yet we constantly fear that they will be derailed by some provocation or intransigence. The action is lightened by the personalities of the Norwegian facilitators, Terje (played by Toby Stephens) the irrepressible optimist who is willing to lie, to be humiliated, to do whatever it takes to keep the dialogue afloat, and Mona (Lydia Leonard) the competent one whom everyone trusts.

Oslo is beautifully directed by Bartlett Sher (no relation of Anthony) and carefully paced with periods of quiet development interspersed with moments of crisis. He never allows the dialogue to run away from the audience. And the ensemble cast do full justice to the play. The actors inhabit these characters totally, so you can believe these are the actual men (and woman) who delivered a peace accord that no-one thought was possible. Oslo rightly earned many awards for its Broadway production last year, and seems likely to repeat that success in London.

——————–

Early reading

11 January 2018

Oxted Cinema reopened last month after a major refurbishment, just in time for the latest Star Wars film, which I went to see a few days ago. Perhaps I will write about that some other time. However, what also caught my eye was a trailer for Paddington 2, the second in what will clearly in due course become a series of films about Paddington Bear. I haven’t been much tempted to go to see it, despite something close to a rave review – for adults as well as children – from film critic Mark Kermode. But it has brought back to mind memories of the books I used to read as a boy.

A Bear Called Paddington was the first in a series of books written by Michael Bond. It was published in 1958, when I was five years old and David was just one. At the age of five I was already reading quite fluently on my own. But my memory is that it was David, not I, who was given the Paddington books and became very fond of them. Paddington is an innocent mischief-maker who finds himself in all kinds of embarrassing situations, perhaps not the kind of character most likely to appeal to me. (As I grew older, I never enjoyed the Just William books either: of course, William’s mischief is much more knowing than Paddington’s.)

A Bear Called Paddington was the first in a series of books written by Michael Bond. It was published in 1958, when I was five years old and David was just one. At the age of five I was already reading quite fluently on my own. But my memory is that it was David, not I, who was given the Paddington books and became very fond of them. Paddington is an innocent mischief-maker who finds himself in all kinds of embarrassing situations, perhaps not the kind of character most likely to appeal to me. (As I grew older, I never enjoyed the Just William books either: of course, William’s mischief is much more knowing than Paddington’s.)

There is a family story that on one occasion, when I was no more than three, I was in the car with Mum and Dad when I said to them that the bus in front was going to London. It wasn’t; but the word London appeared prominently in an advertisement pasted on the back of the bus. And that is how they knew I could read. I’m not sure I believe the story (and I have no memory of it), but I was certainly reading at that age and it’s quite likely that I went around reading things just because I could, even if I didn’t understand them.

I believe that I learned to read by following the words on the page when Mum or Dad read my bedtime story. My favourite book at the time was The Pie and the Patty-Pan by Beatrix Potter, which I liked not because it was a good story (it really isn’t**), but because it was the longest. I came to know it so well that if Mum or Dad tried to miss bits out, I noticed and complained: they had to read every word.

I believe that I learned to read by following the words on the page when Mum or Dad read my bedtime story. My favourite book at the time was The Pie and the Patty-Pan by Beatrix Potter, which I liked not because it was a good story (it really isn’t**), but because it was the longest. I came to know it so well that if Mum or Dad tried to miss bits out, I noticed and complained: they had to read every word.

We had several other Beatrix Potter books. I remember Jeremy Fisher, Squirrel Nutkin, Benjamin Bunny, Peter Rabbit and the Flopsy Bunnies. Jeremy Fisher had a pair of goloshes, and was nearly eaten by a stickleback; two wonderful, evocative words (though I am still not quite sure what goloshes are). There was also a Fierce Bad Rabbit, but I didn’t like that book at all. It was short, and there was a man with a gun who shot at the rabbit.

I have never quite understood the veneration for Potter. Her illustrations are beautifully done, and perhaps you can read some of her books as gentle satires on country life as she knew it, but the stories were quite old-fashioned even when they were being read to me. I much preferred another country tale, How Little Grey Rabbit Got Back Her Tail, written by Alison Uttley and illustrated by Margaret Tempest. There are many more Grey Rabbit books and David collected a good number of them, but this was the first one we owned. It is longer and more sophisticated than any Beatrix Potter, and I suspect that I came to it a little later, but it is a charming book with a better story and far better characterisation than any in Potter, and Grey Rabbit herself is a wholly loveable creation. Why Potter is so revered, while Uttley and Tempest are almost forgotten, is a gross injustice and an unfathomable mystery.

I have never quite understood the veneration for Potter. Her illustrations are beautifully done, and perhaps you can read some of her books as gentle satires on country life as she knew it, but the stories were quite old-fashioned even when they were being read to me. I much preferred another country tale, How Little Grey Rabbit Got Back Her Tail, written by Alison Uttley and illustrated by Margaret Tempest. There are many more Grey Rabbit books and David collected a good number of them, but this was the first one we owned. It is longer and more sophisticated than any Beatrix Potter, and I suspect that I came to it a little later, but it is a charming book with a better story and far better characterisation than any in Potter, and Grey Rabbit herself is a wholly loveable creation. Why Potter is so revered, while Uttley and Tempest are almost forgotten, is a gross injustice and an unfathomable mystery.

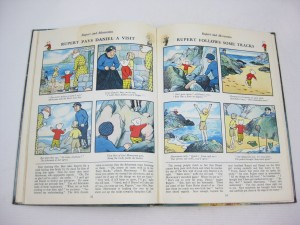

I have no very clear specific memories from pre-school days, apart from one involving a tram (which perhaps I shall write about some other time). But I do have a less specific memory of my bedroom in the then family home at 46 Score Lane in Liverpool. It was a corner room, above the staircase, and I remember Jack Frost’s fingermarks on the windows (no central heating in those days, just plenty of hot water bottles). There must have been some kind of cupboard or bench at the foot of the bed, because I remember that was where I kept my Rupert annuals.

Rupert Bear is a comic strip character of extraordinary longevity. He and his several friends have been appearing in the Daily Express every year since 1920. Mum and Dad did not take the Express, but over time I acquired the annuals which brought together the stories that had been published that year. To summarise Wiki: “the story is told in picture form (…four panels to a page in the annuals), in simple page-headers, in simple two-line-per-image verse and then as running prose at the foot…” I think I generally preferred to follow the verse, which with the pictures was quite sufficient to tell the story, rather than the prose

Rupert Bear is a comic strip character of extraordinary longevity. He and his several friends have been appearing in the Daily Express every year since 1920. Mum and Dad did not take the Express, but over time I acquired the annuals which brought together the stories that had been published that year. To summarise Wiki: “the story is told in picture form (…four panels to a page in the annuals), in simple page-headers, in simple two-line-per-image verse and then as running prose at the foot…” I think I generally preferred to follow the verse, which with the pictures was quite sufficient to tell the story, rather than the prose

One advantage of the annuals was that, unlike the Express, they were in colour. The stories often featured fantastic adventures in places such as King Frost’s Castle, the Kingdom of the Birds, underground, or at the bottom of the sea. I recall that there were one or two stories which I found frightening enough to skip past them in the book. But there was always a happy ending. Would it be fanciful to suggest that my continuing fondness for the magical and exotic can be traced back to Rupert?

Other books which I am sure I was reading from an early age were, of course, the Rev. W. Awdry’s Railway Series, featuring Thomas the Tank Engine, Edward the Blue Engine (always my favourite) and many others. By 1956, when I was three years old, the first ten books in the series had already been published. As you would expect in such a railway-mad family, John, David and I each in turn read and loved these books, and John has recently recovered them from store – they are now, much battered, in the bookshelves at Cark, waiting I suppose for the next generation.

Other books which I am sure I was reading from an early age were, of course, the Rev. W. Awdry’s Railway Series, featuring Thomas the Tank Engine, Edward the Blue Engine (always my favourite) and many others. By 1956, when I was three years old, the first ten books in the series had already been published. As you would expect in such a railway-mad family, John, David and I each in turn read and loved these books, and John has recently recovered them from store – they are now, much battered, in the bookshelves at Cark, waiting I suppose for the next generation.

In fact, on the shelves at Cark John has put quite a number of the books we remember from when we were children, including most of Tove Jansson’s Moomin series. I am not sure exactly when I first came across these, but I think David was already at reading age by then. They have a wistful quality which is quite appealing even to an adult, and though the stories are simple many of the characters feel like archetypes.

In fact, on the shelves at Cark John has put quite a number of the books we remember from when we were children, including most of Tove Jansson’s Moomin series. I am not sure exactly when I first came across these, but I think David was already at reading age by then. They have a wistful quality which is quite appealing even to an adult, and though the stories are simple many of the characters feel like archetypes.

John and David have both also been re-reading Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons series, which are quite evocative for us as many of them have familiar Lake District settings. But those are books for older children than Jansson’s or Awdry’s or Uttley’s.

John and David have both also been re-reading Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons series, which are quite evocative for us as many of them have familiar Lake District settings. But those are books for older children than Jansson’s or Awdry’s or Uttley’s.

John has reminded me of one other series that I am sure I was reading from a very early age: A A Milne’s four books, two of stories and two of poems, about Christopher Robin and Winnie-the-Pooh. Of all the books mentioned here, these alone still have a place in my own bookcase. They are much battered and torn, and it is a long time since I read any of the stories, but I have on a couple of occasions tried to turn some of the poems into songs.  Last year a film was released, Goodbye Christopher Robin, which attempts (not too successfully, I believe) to relate Milne’s writing to his experiences during and after the First World War. Evidently I am not alone in having wistful memories of reading these stories.

Last year a film was released, Goodbye Christopher Robin, which attempts (not too successfully, I believe) to relate Milne’s writing to his experiences during and after the First World War. Evidently I am not alone in having wistful memories of reading these stories.

Milne’s home in East Sussex was not too far away from where I now live, and some years ago Michelle and I went for a country walk in the course of which we found the very bridge on which Christopher Robin played Poohsticks. And if you don’t know what that is, your education is not complete.

** : You can read the whole story, with illustrations, at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Pie_and_the_Patty-Pan. But don’t say I didn’t warn you. There is also an extraordinarily detailed analysis of the book at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tale_of_the_Pie_and_the_Patty-Pan.

——————–

Good year, bad year

11 January 2018

John and I and stayed up until midnight to see in the New Year. It has become a tradition that we do this together and mark the occasion with a small glass each of liqueur – this year, cointreau. We looked back over the year just ended and wished each other good fortune for 2018. We were in Cark, and there were no fireworks; rather a shame, but I do not think that 2017 really deserved them.

It wasn’t a horrible year. I completed the radiotherapy for my prostate cancer and, for now, it seems to be at least in remission. (I will have another blood test and check-up at the end of this month.) In August I completed the course of hormone injections which was another part of the treatment, without too many ill effects apart from some weight gain, which is annoying but not disastrous.

We had two excellent holidays, in Madrid and then Barcelona, which I have written about elsewhere. John and I had two good days at the Old Trafford Test match, watching England get the better of a decent South African team. (It is barely credible that almost exactly the same England team has spent the last few weeks being pummelled by the Australians in Australia. Chalk and cheese.) I saw more than a dozen plays and not one of them was a dud: The Suppliant Women and The Tempest were outstanding.

But politically it was a depressing year, dominated by the slow-motion catastrophes of Brexit and Donald Trump. Even Theresa May’s failure to secure an overall majority in the general election, which at the time seemed like good news, has turned sour. Not only has it left Jeremy Corbyn and (much more troubling) John McDonnell in charge of the Labour opposition, but May is now in thrall to a whole rabble of extremists – in her own party, in the DUP with whom she has been forced to ally, and in the media. With a solid majority she might have been able to steer her own course; not now.

It is just possible to imagine that May is in fact pursuing a secret strategy, to take up hard-line positions (thus assuaging the extreme Brexiteers) and allow herself to be forced back from them by the ineluctable logic of the UK’s weakness: thus we have settled the divorce bill and made concessions over the Irish border. But I do not think she is that subtle. Even if she is, I do not think the Brexiteers will remain complaisant if she makes many more concessions. Most of all, I am quite sure that her red lines over free movement and the jurisdiction of the European Court reflect her personal priorities and beliefs: they are consistent with her stance when she was a notably hard-line Home Secretary.

And I do not think she will be forced to change her position by backbench rebellions. Only one such rebellion has so far succeeded, on a matter which was (in negotiating terms) unimportant, and by a margin of just four votes. There is no sign that rebels have been in the least emboldened by this one success. So far as I can see, the only way things may change is if she faces, and loses, a series of by-elections, and with them her ability to command a majority in the Commons. And even then, Brexit will remain inevitable unless Corbyn reverses his position and agrees that there must be a second referendum on the terms of any deal. For the moment he is clearly more worried about alienating Labour core voters who supported Brexit than about losing the youth vote, overwhelmingly pro-Remain, which secured his unexpected advances in the general election. I think he is wrong about this, but perhaps as the next election gets closer, and the horrors of Brexit become more apparent, he will shift. We can but hope.

I had wondered whether the Irish border issue would force a rethink. It seems inevitable that, if we are not members of the single market and customs union, some kind of border will have to be reinstated, which everyone says they do not want. But the EU seems to have been willing to fudge this issue for now, though it will surely re-emerge not too far down the line. If I were an Irish politician I would be worried that the EU’s robust words of solidarity had been followed by temporising actions, and would be lobbying furiously for no further compromise on the objective of a soft border.

But what I find even more troubling than Brexit itself is the fact that so many people voted for it in defiance of their own best interests. No doubt their votes reflected dissatisfaction with the state of the nation, particularly away from London and the South East. No doubt, too, that the meretricious Brexit campaign, backed by most of the popular press, trounced the abysmal efforts of the Remainers. I listened in vain for anyone to speak of the benefits of EU membership, though to me they are obvious: not just economic prosperity, but the protection of human rights (not least employment rights), the attention to environmental issues, the challenge to over-mighty tax-avoiding multinational corporations, and above all the attainment of peace among the widening circle of member nations. Last year’s general election gave us another reminder that the electorate can still be swayed by a good campaign or alienated by a bad one.

But I still think it astonishing that obvious charlatans like Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson were ever able to command such attention and credibility. And it is profoundly worrying that shadowy figures like Paul Dacre and Arron Banks have exercised such influence. The risk will be all the greater when, post-Brexit, none of the alleged benefits come to pass. Austerity, declining public services, low wages and economic imbalance will all continue. We are extremely fortunate that we do not (so far) have the equivalent of a Trump or a Le Pen. If we did, we would be in even worse trouble than we are already.

Parliament is supposed to be a bulwark against demagoguery, but has proved to be a broken reed. MPs like Bill Cash, who has built an entire career out of opposing the UK’s membership of the EU, have at least been consistent. But I find it less easy to forgive those Conservative MPs who supported Remain, and are well aware of the damage that Brexit will do, but have switched sides since the referendum. No doubt they are genuinely worried that if they rebel against May they may precipitate a General Election and open the way for Corbyn to become Prime Minister.

But you have to draw a line somewhere. I am surprised that Michael Heseltine’s warning to Conservative MPs has not been better heeded: ““We have survived Labour governments before. Their damage tends to be short-term and capable of rectification. Brexit is not short-term and is not easily capable of rectification….” The Government’s one defeat to date on its Brexit legislation came on an amendment to protect (some of) the power and rights of MPs to hold the executive in check. But those same MPs seem very reluctant to exercise the power which they still have.

There have, of course, been exceptions. I have been very impressed by David Davis’s opposite number Keir Starmer: the right man for the job, though demolishing Davis in debate must be one of the easier tasks in opposition. Hilary Benn has been doing good work as chair of the Parliamentary select committee. And on the Tory side I have been impressed by Dominic Grieve who led the one successful rebellion. Not all Tories are craven hacks. But Starmer needs to do more work on Corbyn and the shadow cabinet, and Grieve on his fellow backbenchers, if anything is to change in 2018.

And that’s all without saying another word about Donald Trump. No; if you are a moderate, liberal democrat (small L, small D) as I am, 2017 was a depressing year. Let’s hope that, despite the portents, 2018 turns out a bit better.