Ghost in the Shell (2017)

26 June 2019

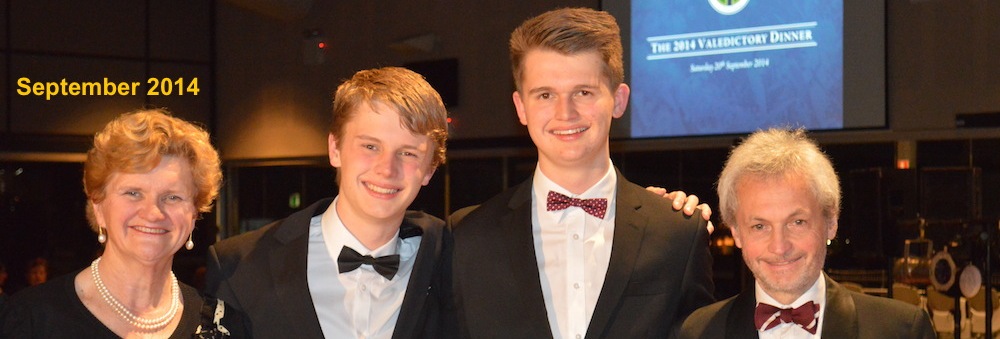

Ghost in the Shell is a science fiction/cyberpunk movie, released in 2017. It is set in an unnamed dystopian future metropolis that might be Tokyo or Hong Kong thirty or forty years from now. The protagonist, known only as Major for most of the film, is played by Scarlett Johansson. Juliette Binoche also has a featured role, alongside numerous other actors I had never heard of. I borrowed the DVD from Cinema Paradiso and have now watched it twice on my (fairly) large-screen TV. The film’s action and backgrounds are spectacular and would probably have been better in the cinema, but I didn’t have that opportunity.

The basic premise is that Major is a cyborg, a human brain encased in and controlling a superior mechanical body. She is the latest in a long series of experiments to achieve this fusion, but the first to be successful. All that she has been told is that she was the victim of a terrorist atrocity and that her brain was the only part of her that could be saved. Over the objections of her creator Dr Ouelet, played by Binoche, she is employed as an agent by an elite counterterrorism unit.

I don’t know whether John has seen the movie but I am fairly sure that he despises it anyway. GitS is a live-action adaptation of a Japanese anime film from 1995, directed by Mamoru Oshii, which was in turn based on a manga of the same name by Masamune Shirow. These are genres with which John is very familiar, and I suspect he would join many aficionados in saying that the movie fails to do justice to the original material. Other critics have said they found it confusing, and that the plot was full of holes.

Well, I enjoyed the film. It isn’t a masterpiece, but it is decent entertainment with some thought-provoking elements. I wasn’t confused or troubled by any plot holes. There is a big twist half way along, and only then is the true antagonist revealed, though we might have guessed sooner if we had been really paying attention. On first viewing I thought there were one or two gaps in the logic of the story, but on reflection and re-viewing they have quite clear explanations: the clues are all present and we are expected to fill in any gaps for ourselves. I far prefer this to being spoon-fed.

It is true that if you were unfamiliar with the conventions and tropes of cyberpunk you might find it a little difficult to keep up. In a two-hour film not too much time can be spent on exposition; audiences are expected to fill in the blanks for themselves. However, GitS is good at introducing the key plot elements while taking the background pretty much as read. You might quibble about some of the detail, but the external shots, in particular, are very effective in conjuring up a nightmarish future, with a glittery neon-lit surface and a grimy concrete underbelly.

Some bloggers about the film criticise the performances. Now, in a film like this you should probably not expect great acting. It mustn’t be wooden, and needs to be true to character and setting, but anything more is arguably wasted. In fact I thought Scarlett Johansson was better than that. She embodies the concept of the cyborg really well, reminding me of Alicia Vikander in Ex Machina (see my blog of 12 January 2018).

None of the other performances fail my basic test; they remain credible and don’t break the illusion. That said, I was very taken with Takeshi Kitano, who plays a counterterrorism boss, Aramaki. He exudes authority and depth, and effortlessly steals every scene that he is in.

When the film was still in production there was controversy (which at the time almost passed me by) about the casting of Johansson and other western actors in a film based on a Japanese original. So far as the finished product is concerned, Johansson is made up to look very like the manga character, and the idea that in this future metropolis many different ethnic types are represented seems fine to me. Most of the criticism seems to have come from the US-Japanese community and others who feel themselves under-represented in Hollywood; I think I detect the grinding of axes, which GitS deserves no more than many other movies. Notably, Mamoru Oshii, and Japanese audiences generally, have been untroubled by it. And the fact is that if Johansson or some other bankable actress had not been cast, the film would probably not have been made at all.

I have a little more sympathy with the criticism that the movie fails to capture all the nuances present in the original material. I’ve not seen or read the originals, so have no first-hand basis on which to make the comparison. (I have, however, found several sites online which do so. See, for instance, https://bit.ly/2FwUNvl.) But I can think of plenty of movies and TV series which fail this test, so I can well believe that GitS is another.

That said, I don’t think GitS lacks substance. The film is suffused with classic cyberpunk themes: urban alienation, the impact of technology on humanity, identity, the mind/body debate and the rise of megacorporations. The main antagonist in the film turns out to be one of these corporations, which is apparently a significant change from the original story, but it fits very well with the context and genre.

Where this movie must surely score over its predecessors is in the action sequences, which draw on a variety of influences and are uniformly stunning. Within the first five minutes of the film Major has overwhelmed a troop of assassins in an acrobatic fight that might have come from a kung-fu movie. Towards the end, she defends herself against assault by a killer robot (shades of RoboCop). But perhaps the most dramatic fight takes place in the shallow waters of the city harbour, hand to hand between Major, in a chameleon suit which renders her almost invisible, and a mind-controlled thug.

It must also score in the grim reality and contrasts of its design. I’ve been searching online for stills from the movie to illustrate this and have included a couple with this blog, but they are curiously hard to find. A better illustration may be found in an official trailer for GitS, https://bit.ly/2fnUgzC. Don’t be distracted by the mayhem: focus on the anonymous, tech-heavy interiors and the bleak, dehumanised exteriors which set the mood of the film.

The trailer also shows Major/Johansson in action in her chameleon suit. Most of the time she wears ordinary clothing, but when she goes into action she strips off and we see the smooth body-hugging cybersuit underneath. (In reality I imagine it is some kind of body stocking.) You might think this was a bit of gratuitous titillation, and Johansson is certainly shapely, but the effect is curiously asexual. The bodysuit conceals all her naughty bits and renders them inert.

Back in the 1950s, much screen science fiction was B-movie stuff, killer ants and blobs and things from outer space, all of it metaphors for the so-called Communist menace. We have moved on since then. Recent SF movies and television shows are more interested in exploring technological dystopias: the things we do to ourselves. Apart from GitS, Blade Runner and Ex Machina (though in Ex Machina the -punk is absent) there has also been the Netflix series Altered Carbon, based on Richard Morgan’s outstanding novel of the same name. Similar themes can be found in all three Matrix films. The metaphor has become the substance, a generalised fear of exploitative and runaway technology.

For what it is worth, I do not believe that the mind and body can be so easily separated as GitS suggests. If there is something in us which we call our soul, what GitS calls ghost and the Romans called anima, it is shaped by what we experience in our bodies from the moment of our birth. No wonder, as the film tells us, that Dr Ouelet had so many failures before Major; no wonder that Major is troubled by fragments of lost memory, by a sense of alienation. The reality would be much, much worse. Still, it makes for a good story.

——————–

The West Wing

25 June 2019

I have in the last few minutes finished watching the last three episodes of the second season of The West Wing television series. This is the sequence in which President Bartlet (played by Martin Sheen), having just revealed to his senior staffers that he suffers from MS, has to find his way through multiple crises, including a coup d’état in Haiti in which American lives are threatened, the death in a car accident of his loyal personal secretary Mrs Landingham (Kathryn Joosten), and finally a press conference at which he must announce whether he will run for a second term as President.

When TWW was first broadcast, American TV network executives worried that its presentation of a fictional Democratic president would run them into trouble with Republican audiences and politicians. Consequently, during its first season and into the second, the show’s creator and principal writer Aaron Sorkin took steps to nod to Republican sensitivities, making Bartlet fiercely patriotic and a devout Christian, and including a declared Republican on his staff. But in these three episodes he nails his colours to the mast. Bartlet is depicted as a truly heroic figure determined to battle against the odds, including the doubts of his own closest supporters and the fears of his wife, to seek a second term in order to pursue the interests of the poor, the sick and the excluded.

In the final scenes of the second season, we see Mrs Landingham’s funeral at the National Cathedral, intercut with flashback scenes from when Bartlet first met her. Bartlet asks for the cathedral to be cleared and addresses God directly, in English and Latin, demanding to know what he has done to deserve this punishment, and cursing God for his cruelty and indifference. Then he goes out of the cathedral into a fierce storm, which I think is intended as a metaphor for being rebaptised. He is confronted by a vision of Mrs Landingham who urges him, if he wants to continue as President, not to give in to his fears. In the final scene we see him newly inspired to declare that he will seek re-election.

The concluding minutes are accompanied by Dire Straits’ song Brothers in Arms. Even if you don’t like Dire Straits, the music here is a perfect fit. The cumulative impact of these scenes is awesomely dramatic, and I use the word advisedly: it is enough to raise the hairs on the back of your neck. At the climax I found myself gripping the arms of my chair, which usually I only do in the car when John is driving too fast.

I see, however, that I have got ahead of myself. I bought my DVDs of TWW years ago, when the series was still fresh. I had seen many episodes from the first season, and some from the second, when they were broadcast in the UK, and then I stopped watching. I’m sure it wasn’t because I had lost interest, but in those days, as now, I found it very difficult to keep a date with any television programme at all regularly.

Anyway, I bought the DVDs, put them in a cupboard and forgot about them. Then, a fortnight ago, I discovered that my telephone line had gone dead, though the broadband oddly was still fine. The first repairman left things worse than before, with both phone and broadband not working. The second engineer, who came yesterday, fixed the faults (one of which was that the wires had been reconnected wrongly) and restored the service. The practical effect meanwhile was that I had to find other entertainment for a few days. So I ransacked my cupboards, and there were the DVDs of TWW lying neglected in a corner.

The show was broadcast over seven seasons, from 1999 to 2006. Despite the initial controversy, it was an immediate hit with critics and audiences. There was fulsome praise for the performances by the ensemble cast, for direction and cinematography, for production values and above all for the writing. Here are remarks from a review of the very first episode:

“ ‘Nice morning, Mr McGarry,’ says the guard. ‘We’ll take care of that,’ says Leo, as he passes through a corridor, an office, another office, a corridor, an office, five corridors, an office, a corridor, an office, a corridor, two offices, a corridor and two more offices before settling behind his desk 3 minutes and 26 seconds later. He has 12 separate conversations and 133 people pass in and out of the picture. That’s more extras than populate some series in a whole season.”

[Me again.] Not to mention the skills required from the actors, the director and other production staff in sustaining such a lengthy virtuoso sequence. The walk-and-talk, which gives dynamism to what could otherwise be quite static material, became a trademark of the show and has been regularly copied by other shows ever since.

I don’t want to spend too much time on the uniformly excellent performances, which have been widely praised elsewhere. But a special word must go to Alison Janney as CJ Cregg, the Press Secretary. Her character is wrong-footed from time to time, but she more than holds her own in a group of high-performing alpha-plus males. Of them all she is the only one I can like without reservation. She represents a major advance in how women are presented on American television, and on ours.

Otherwise, though we are clearly meant to root for Bartlet and his team, they aren’t always very admirable. Bartlet himself has a temper and an edgy relationship with his wife (played with conviction and dignity by Stockard Channing), though clearly they love each other. Leo McGarry (John Spencer) is Bartlet’s Chief of Staff, which means he is an intermediary between the President and the outside world, a friend and confidant, a political fixer and boss of the other staffers, including Toby (Richard Schiff), Sam (Rob Lowe) and Josh (Bradley Whitfield). From time to time the staffers are arrogant and overbearing. What saves them from being unlikeable is that they so obviously care. And the issues they tackle are real issues: poverty, education, crime, drugs, conflict overseas.

Sure, we also get to see moments from the characters’ private lives, but they are not the principal focus, and the show never descends into soap opera or melodrama. It has in fact been praised for the accuracy with which it depicts American political processes and institutions. But it rarely becomes didactic. Much of its drama comes from the conflict between good political intentions and the real facts of political life – favours traded, arms twisted, realpolitik in all its forms. The good guys don’t always win, and we get to see why.

One other feature of the show that I particularly admire is that it isn’t neat. Any given episode may have three or four separate plot threads running through it. Sometimes an episode has no main plot at all, just a pile-up of different subplots. Separate threads run at different speeds; sometimes they never reach any conclusion at all. The effect is to show the untidiness of real political life, and to leave us to work out for ourselves how, or whether, the purposes of the Bartlet administration are being advanced or sidetracked or curtailed. This is far superior to the easy option of one story per episode, neatly tied off at the end.

It’s impossible to imagine a similar show ever being made about British politics. The BBC is bound tighter than ever by its neutrality. Its last attempt was House of Cards, which is thirty years old (yes, ten years older than TWW), and that was a satirical drama, not a serious attempt to show the truth of our political processes. Meanwhile the commercial stations have abandoned all ambition beyond soap operas, police dramas and reality shows.

So I think it’s useful, and reassuring, to be reminded that politics can be more than just ambition and spin. When the show was first broadcast, George W Bush was about to become President, and during his years in office TWW showed viewers that politics can be better than this. How much more do we need that reminder now, in the age of Trump and Johnson and Brexit.

——————–

Three choirs

19 June 2019

During the last six weeks I have sung with three different choirs at three different concerts with three different programmes. It has been quite an experience.

The first concert was with my own Hurst Green Singers, at St John’s church in Hurst Green, just a couple of miles down the road from where I live. I have written previously about the process we went through to appoint our new Music Director, James Meaders (see blog of 3 April 2018). Our expectations from Jamie have if anything been surpassed. The choir really likes him and responds to his coaching. He has raised our standards of performance considerably. And he has introduced us to music, classical and contemporary, which we would never otherwise have encountered.

Our concert on 11 May was our second under Jamie’s direction. Accompanied only by piano, we performed the first four movements from Will Todd’s Songs of Peace, Mozart’s Solemn Vespers, and an Ave Verum, also by Mozart. As often happens, half way through the programme of rehearsals I really thought we would never be ready in time for the concert, but this was unduly pessimistic. We were not perfect, but we were a lot better than average. Jamie was pleased and said we were quite good, which was a bit disappointing until we and he realised that this is just American for very good.

The Will Todd was a completely new departure for us. Todd is a living English composer whose music has a strong tinge of jazz rhythms and harmonies. I was not at all sure what the choir would make of this, and the basses did find parts of it quite difficult as they bore the brunt of the unfamiliar harmonies, but everyone else I have spoken to, including members of the audience, really loved it. However, I don’t think Jamie will be giving us too much more jazz-influenced music to sing for a while, as he had to work really hard to coach us into the swing that it requires.

When Jamie first came to the UK he not only became the Musical Director of HGS but also set up his own local choir at the village of West Malling in Kent, north of Maidstoine, 25 miles from here. The choir is called Vox Populi (Voice of the People), and last Christmas several of us went to hear their first concert. Afterwards I asked to join, and so was one of the singers at their second concert, held on 18 May in the village church at Mereworth (pronounced Merry-worth) between West Malling and Maidstone.

We sang four pieces, all by living composers: For a Breath of Ecstasy, by Michael John Trotta, which is a seven-movement work setting poems by the American poet Sara Teasdale; Lullaby and Ballade to the Moon by another American, Daniel Elder, setting his own words; and Luminous Night of the Soul by Ole Gjeilo, a Norwegian living in New York, using new words by Charles Anthony Silvestri and lines from St. John of the Cross. Jamie apparently knows all of the composers personally.

The Gjeilo was great, performed with piano and string quartet, building to a terrific climax, although it is a slightly odd piece: it is interrupted early on by a long piano solo that doesn’t seem to me to bear much relation to the rest of the work. The two short Elder songs, accompanied by piano alone, have a sweetness that falls just barely the right side of cloying, and are quite challenging to sing well as they require a lot of control of tempo and dynamics as well as enunciation and pitch.

In rehearsals I was less impressed with the Trotta which is harmonically unadventurous, mostly not very interesting to sing, and recycles a few musical ideas for more than they are worth. In performance, however, we were accompanied by string quartet and solo oboe, and the oboe (played by a former member of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, no less, now living in retirement locally) gave the piece a character it had previously lacked. I must say, though, that I think the music I write is at least as interesting as this, and doesn’t overstay its welcome.

Jamie is not just conducting these two choirs. During the year he has twice been over to New York, as a guest conductor for concerts at Carnegie Hall and the Lincoln Centre. The model for these concerts appears to be that a number of choirs are invited to participate, mainly but not only from the USA, and each performs one or more items on the programme. So there is a certain amount of shuffling around on stage between items. Jamie has imported this model to the UK, and organised a concert at the Cadogan Hall on 1 June with a mixture of choirs from the USA and the UK, including Vox Populi. Apparently this is to be an annual event. Jamie didn’t conduct the whole programme: he shared duties with two other American conductors, Joseph Wilkinson (whom I didn’t encounter) and Christopher Crook.

My share of proceedings was to sing two different pieces with two different choirs. Before the interval, a group from Vox Populi and from an American choir performed For a Breath of Ecstasy, conducted by Crook. We sang it pretty well, but we had a different oboe player who was less able to awaken the dormant spirit in the music. After the interval Jamie led a large combined choir (80+ members) in a long work with full orchestra, Jubilate Deo by Dan Forrest, yet another American composer, who had come over from the States to support us.

I, and the few other British participants, had had to prepare for this on my own, learning the piece from the printed music and with the aid of recordings available on YouTube. So the first time I had sung it with a choir was at the first rehearsal which took place just two days before the concert. I had been quite worried that I would be well off the pace, but in fact it was fine; the most intimidating part was not the fact of rehearsing a choir for the first time so soon before performance, but that the other tenors in the choir were so good. I have no illusions about my own modest abilities as a singer, but good tenors are rare, and my contributions are usually valued, whatever my limitations. On this occasion I was utterly outclassed.

Forrest’s Jubilate is a setting of Psalm 100 in seven movements and in seven different languages. As well as English and Latin we had to sing in Hebrew, Arabic, Chinese, Zulu and Spanish. The music is intended not to mimic national styles but to incorporate and echo elements of those styles. The fourth movement, in Zulu, was a beast to learn, but great fun in performance, with several percussionists in the orchestra bashing and banging and shaking away. The whole piece isn’t great music exactly, but it is expertly put together with plenty of character, and we all enjoyed singing it.

Jamie again proved himself to be an excellent conductor. It cannot be easy to lead a large group of singers in music which they have learned in separate groups under different leaders, or (like me) on their own; but he succeeded both in communicating his on pleasure to us and in getting us to sing as a single choir. Perhaps those two things go together. He had also found, or assembled, a first-class orchestra to support us. The music must have been unfamiliar to all the players, and it cannot have been easy (harder I think for orchestra than choir), but they too performed to the manner born. As for the choir, we were not perfect, and there were one or two moments at which I would have winced if I had been in the audience, but overall it was a very successful occasion.

Michelle came to the concert to lend her support, and said afterwards that she had enjoyed it a lot, more than she had expected. She knew it was all music by contemporary composers and I think feared the worst (as John would say, all clashing chords), so was pleasantly surprised. The Jubilate really deserves to be better known here, though I suppose its effectiveness comes in part from the orchestra’s contribution, which would be beyond the reach of most small choirs.

——————–

The decline of cricket

18 June 2019

As you can no doubt imagine, I have been following the cricket World Cup (just ending its third week) closely, or at least as closely as I can. It is not being shown on free-to-air television, so the most I can do is follow the ball-by-ball commentary on BBC radio. Most of the time I prefer the reportage on two websites: the Guardian, whose writers offer comments over by over, and Cricinfo, which goes ball by ball but with less insight or style. The match reports and analysis on these two websites are also very good, especially by George Dobell of Cricinfo and Vic Marks of the Guardian.

Reports on the Guardian are very often open for contributions “below the line” (btl) by bloggers, some of which are very observant and thoughtful. But a theme has predictably emerged in the btl comments: how disastrous it is that this World Cup is not being shown free-to-air, and thus is failing to engage a wider audience. The statistics which show declining interest and participation in cricket in England are undeniable. So, without doubt, this has been a missed opportunity.

I do not agree with the bloggers who lay all the blame at the doors of the England and Wales Cricket Board (the ECB). The ECB took a decision in late 2004 to assign all live television rights for England’s home matches to Sky TV; so the last free-to-air home Test series was the Ashes in 2005. But at the time, the ECB’s negotiators had to address two plain facts. Cricket in England was in danger of financial collapse. The county clubs which provide the bedrock for the first-class game had become dangerously dependent for their survival on the income from broadcasting. At the same time, the free-to-air broadcasters were losing their appetite for the game.

Cricket is not technically difficult to broadcast, but it is very difficult to schedule. Free-to-air broadcasters are obliged to please their diverse audiences. The BBC has to justify its licence fee and the commercial stations to satisfy their advertisers. There simply is no room in modern TV schedules for Test matches, which are booked to last five full days although they may be over in three, or even for a World Cup final which takes a whole day. Matches may be interrupted by the weather. When play is interrupted, or ends prematurely, broadcasters have to fill in with talking heads or with recordings of previous games. Prime time television cannot afford such indulgence.

Sky TV on the other hand was and is desperate for live content to satisfy its subscribers. To the ECB it must have looked like the answer to a prayer. Perhaps they were too ready to sign an exclusive deal; perhaps they should have tried harder to find a compromise that would have kept at least some cricket on free-to-air television. But that would have required them to overcome the increasing indifference of the terrestrial broadcasters. Details of commercial negotiations are rarely shared with the world, so we do not know whether compromise deals were offered, or why they were rejected.

The negotiating team was led by Giles Clarke, who subsequently became Chairman of the ECB. Clarke was later implicated when Kevin Pietersen, a popular and highly talented batsman but a disruptive presence in the England team, was permanently dropped. He was also at the heart of a plan, later aborted, to reshape international cricket’s ruling body to give more influence and income to England, India and Australia at the expense of all others. So it is not surprising that Clarke has become a hate figure among cricket supporters and bloggers. Perhaps it goes with the role. His successor Colin Graves is, for different reasons, equally unpopular.

The ECB must take its share of the blame; but only a share. I believe that there are other reasons why interest and participation in cricket are in decline. And I can suggest some other figures to take their place in the gallery of shame alongside Giles Clarke.

It is common ground among bloggers, and probably true in fact, that cricket needs to reach its potential audience when they are still young. When I was a boy we were playing cricket regularly at school (see my blogs of 3 and 10 July 2018). Remember this was a state school, not one of the wealthy fee-paying public schools. Our playing fields at Mersey Road had an excellent cricket pitch, tended by groundsman Edwin Wass who was himself the son of a former first class cricketer. We played, including at weekends, under the supervision of one or other masters in charge who gave up their own time to support us.

None of that would happen now. My first figure of scorn is Margaret Thatcher, who never really understood the value of sport and gave it little attention among other priorities. During the 1980s, under her government, something between 5,000 and 10,000 school playing fields were sold for development (online sources quote both these figures). Alas, our beautiful ground at Mersey Road was one such; it is housing now. My school was closed in 1986, but another could have taken over the ground. Its abandonment was and is a shame and a scandal.

Also under Thatcher there was a long-running pay dispute which ended with much bitterness among teachers. Thatcher was obsessed with breaking the power of the trades unions, but whether or not you sympathise with that policy it was crassly applied to the teachers. Who (apart from the medical profession) contributes more to society than they do? And whose goodwill, therefore, is it more necessary to retain? The teachers retaliated by withdrawing from all extracurricular activities, and school sport was among them. This was perhaps not very generous; but in the circumstances they had few other ways to make their point. I do not believe that voluntary effort has ever been truly replaced.

The second figure in my rogues’ gallery is Tony Blair. No doubt Blair had a better understanding than Thatcher of the place of sport in society. But he fell into the thrall of a management guru called Michael Barber whose simplistic view was that to achieve better public services you should define what you want from them and set targets accordingly.

I could write at length about the folly of this, but for now let’s stick to education. The targets set for schools, and the league tables that are drawn up based on performance against these targets, continue to be hot topics of debate. But it is clear that everything not covered by targets is given no priority, and that includes school sports. As a result, if you want to play schools cricket (at least outside Yorkshire where old traditions die hard), you almost need to go to a public school, and this is increasingly reflected in the composition of he England team. Barber’s ideas would have been harmless but for Blair’s endorsement, so it is Blair who must carry the blame.

Third among my rogues is more of a totem, a representative of a change in society which he has helped to bring about. I don’t suppose Mark Zuckerberg has given more than five seconds’ thought to cricket in his entire life. But it is Zuckerberg’s Facebook, along with Amazon, Google, Apple, McDonalds, Uber and the rest of them, who have fuelled a new culture of instant gratification. Modern audiences have learned to be impatient; but cricket is a game of a narrative, indeed of stories within stories, which take time to evolve.

My fourth and final villain is of a different order entirely, and of them all must be the chief, because his villainy is personal and is still taking place. Rupert Murdoch’s money, through Sky, is supporting cricket. But that money is a drop in the bucket compared to the billions that Sky, with Murdoch’s personal blessing (how could it be otherwise?), has poured into professional football. It was a quite deliberate strategy to use football as a marketing tool for Sky, while at the same time giving football a massive pre-eminence. No wonder that cricket, along with other sports, is struggling for an audience. Football, fuelled by Sky, wants it all.

I think, by the way, that lovers of football may yet come to regret their sport’s own devil’s bargain with Murdoch, if they don’t already. But that is another story.

——————–

Woman to Woman

10 June 2019

In my whole life I don’t think I have been to more than a dozen pop/rock/jazz gigs. Let’s see. There have been three Al Stewarts (at Oxford Town Hall, the Hammersmith Odeon, and then – bizarrely, given the nature of Stewart’s music – at the Albert Hall); two Judie Tzukes, at the Apollo Victoria and at the Fairfield Halls in Croydon; one Carole King, at the Dominion theatre; one Modern Jazz Quartet (that was really dull) also at the Dominion; and most enviable of all, one Kate Bush in Paris, where I happened to be on holiday at the time. I can still remember the Parisian audience snapping their cigarette lighters in tribute. Obviously the French have never heard of health and safety or fire regulations, or else they don’t care. Anyway it was a memorable occasion.

If you stretch the definition of gig broadly enough I could also include Claire Martin at Ronnie Scott’s (hint: go for the jazz or for a drink, but not for the food), and even a second Claire Martin at the very staid Oxted and Limpsfield Music Society, though I’m sure its members would recoil at the word gig. But until last week that is the sum total that I can recall.

Now, however, I have another event to add to the list. Last Friday I took Georgina to the Cadogan Hall, just off Sloane Square in London, to hear a concert given under the title Woman to Woman by three singers whose careers peaked in the 1980s and 1990s: Judie Tzuke (again), Julia Fordham and Beverley Craven. I’d be hard pressed, now, to say how exactly I became aware of this event: but it was way back in 2018, so long ago that I misread the concert date as 7 Jan not 7 Jun, and only realised my mistake a few days beforehand, which was rather embarrassing. Fortunately, Georgina laughed, and forgave me.

Cadogan Hall is not the most obvious place for a pop/rock gig. It was originally a Christian Scientist church, as can still be discerned from inscriptions on the exterior walls, but was abandoned as such in 1996. After a couple of changes of ownership the Hall was redesigned and refitted, and opened as a concert venue in 2004. It is now the permanent home of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Until a week previously I had never visited the Hall, and then did so as a performer in a choir, about which I will write a separate blog. So Woman 2 Woman was my second visit in a week.

This was not one of those stadium rock shows at which there are lasers, strobe lighting, coloured smokes and other extravagant display. What we got was a five-piece band (guitar, bass guitar, sax, keyboards and percussion) supporting the three singers. Beverley Craven performed at a grand piano, and Julia Fordham occasionally took up a guitar. There was some very restrained spotlighting and, for the most part, discreet use of amplification: enough to be heard, not to distort. There was also a massive video screen at the back of the stage – we’ll come on to that. But this was definitely a concert, not a show.

We certainly got our money’s worth, two and a half hours of performance plus interval. Each of the three women in turn took the lead while the others provided backing vocals, and there were also a small number of pieces, mostly new, for the trio together. The songs were, I think, a mixture of greatest hits and old favourites plus new material – but I can only say this from being told, not of my own prior knowledge.

Actually, that is being a bit unfair to myself. I was, and am, a fan of Tzuke’s early albums: I have a CD of the first two which I listen to when driving. Among the songs on her first album is Stay With Me Till Dawn, which provided her only UK hit and is one of the simplest, sexiest pop songs I know. It suits her voice perfectly but its power is due, I think, mostly to a very effective bass-heavy arrangement which makes the song properly momentous: you feel this is a significant moment in the singer’s life. However, its simplicity is not entirely typical of her early songs which are otherwise characterised by adventurous harmonies and an unusual approach to word-setting which sets up cross-rhythms. They also benefit from clever, sensitive arrangements. Unfortunately, after her second album her songs seem to have become more formulaic, and after the fourth album I lost interest. As if to bear this out, for this concert she selected mostly from the first album, including of course Stay With Me… which predictably brought the house down.

Although I was keen to hear Tzuke again after such a long interval, I was most curious about Julia Fordham, whose name I recognised without being able to connect it with any particular song. I had in mind, I think, that her music was jazz-influenced, which turned out not really to be true. She did sing one definitely jazz song which I really liked, and incidentally showed off the versatility of her backing musicians. But Fordham, like Tzuke, mostly concentrated on her earlier hits, including Happy Ever After and Porcelain, which allow to exhibit the brilliant clear tones, vocal agility and range that she still possesses. Happy Ever After is another good song made great by its arrangement. I’m sure that the performers at the concert were not simply miming – there were a lot of little giveaways – but they did remarkably well in concert to emulate the original studio sound.

Of the three singers it was Beverley Craven of whom I knew the least. I had a vague idea in my head associating her with some disco hit or another, but quite obviously that was wrong. In fact Craven, like Fordham and many others, is a singer of pop ballads, mostly written by herself. Her greatest hit was Promise Me and she had several other successes. I thought her voice and songs less distinctive than either Tzuke’s or Fordham’s, but to compensate for this she is clearly a talented pianist and also displayed a mastery of comic timing in her remarks between songs.

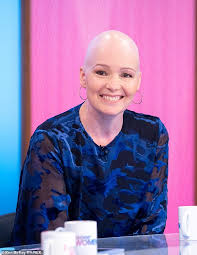

But what was most remarkable about Craven was that she was appearing on stage only weeks after chemotherapy to treat a second bout of breast cancer (previously in 2004, again in 2018) and a double mastectomy. Emotions on stage and off were clearly running high. Apparently earlier legs of the Woman 2 Woman tour had to be postponed while she received treatment; if this was not her first comeback concert (but I think it may have been) it was very close.

On the screen behind the stage, videos were played which in many cases were the original music videos from when the songs were first released. This made it impossible to avoid comparisons of how the women looked then and now. Fordham was a slender beauty, and is still elegant and distinguished. Craven is completely bald from the chemotherapy, not hiding behind a wig, and barely recognisable from her former intense self; but to make up for it she has the kind of poise that tells of experience gained. I thought Tzuke showed the saddest change: once petite and glamorous, her frizzy hair is now grey and looks unkempt (though I am sure it is not), and she has lost all her delicate fragility.

It must have caused some agonising to show these videos of their former selves. But I also thought it in keeping with the theme of the show. Many of their more recent songs draw on experience as women and mothers which they could not have written at the start of their careers. In effect we were being asked to remember what they (and we?) once were, but also to accept without regret what they and we are now, and anyone who didn’t get this feeling will I think have missed the point of the concert.

Their final song, performed in harmony together, was Safe, which is a celebration – almost a recitation – of the things to be valued most in life. Georgina said it was her favourite song from the whole show. I’ve included a link to a video below, though as you will see it must have been recorded some months ago.

Stay With Me Till Dawn (Judie Tzuke) : https://bit.ly/2Wpe1bS

Happy Ever After (Julia Fordham) : https://bit.ly/2I6srth

Porcelain (Julia Fordham) : https://bit.ly/2WXdJNM

Promise Me (Beverly Craven) : https://bit.ly/2sBVa3C

Safe (Tzuke, Craven, Fordham) : https://bit.ly/2I4UOs2

——————–

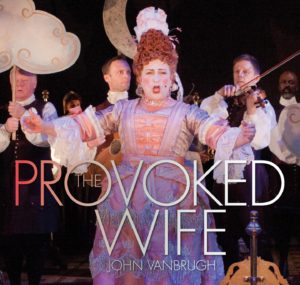

The Provok’d Wife

9 June 2019

Yesterday John and I went to Stratford-on-Avon to meet my friends Chris and Janet and to see the RSC’s current production of Vanbrugh’s The Provok’d Wife in the Swan theatre. Many years ago I saw the play at the National Theatre in London, but I had no recollection of it apart from enjoyment. John had never before seen it; neither had Janet or Chris.

Vanbrugh seems to have been a remarkable man. He was a radical, among the instigators of the Glorious Revolution in 1688. By the age of 30 he had been a political prisoner for four years in France. He then turned to the stage, writing two hit plays (The Provok’d Wife and The Relapse) which are still revived; he is remembered as one of the leading Restoration playwrights alongside Etherege, Congreve and Wycherley. But he wrote nothing else, and his most enduring claim to fame is as the architect of, among other notable buildings, Castle Howard and Blenheim Palace. Truly a Renaissance man. If there are dinner parties in Heaven you imagine that he is a much sought-after guest.

Restoration comedy has a reputation for sexual frankness and immorality. The RSC programme quotes Vanbrugh himself: “The business of comedy is to shew people what they shou’d do, by representing them on the Stage, doing what they shou’d not.” But if any of us had expected the bawdy humour of, say, Wycherley’s The Country Wife, we were in for a surprise. The Provok’d Wife takes the stock situations of farce and gives them a distinctly vinegary quality.

The central figure is Lady Brute (the naming conventions of Restoration drama are preserved: other characters include Constant, Heartfree and Colonel Bully), whose husband is indeed drunken and brutish. The central question of the play is should she take a lover and, more to the point, is she justified in doing so? By the end of the play her dilemma is unresolved. There is a conventional happy ending in which a malicious plot is thwarted and a marriage is arranged, but Lord Brute is still brutish, his wife trapped and the future unclear.

Vanbrugh was surely far too clever a man not to have understood and intended what he had written. With a tiny twist in the plot he could have given his play a bitter, bleak ending. In a programme note, the director of this production, Phillip Breen (surely a man to watch), describes The Provok’d Wife as foreshadowing Ibsen and Pinter. I can see exactly what he means. This may be nominally a comedy, but there are dialogues between the leading men and (separately) the women about the nature, the compromises and pitfalls of marriage which have a razor-sharp edge to them.

Breen not only has a clear view of the play’s true nature but has imparted it to this excellent production. There is none of the directorial invention/intervention which has marred one or two recent RSC productions (see for instance Mrs Rich, blog of June 2018). It is played as straight as the script allows, in period costume and with a minimum of props to suggest location when it matters and to underscore character. There is one tiny piece of cross-gender casting (another recent RSC hallmark) in one of the supporting roles, but blink and you will miss it.

He is aided by an unusually stellar cast. Lord Brute is played by Jonathan Slinger, who must by now be regarded as an RSC veteran, having taken the leading roles in Hamlet, Macbeth, Richard II and Richard III. Lear will surely follow. He was unknown when I first saw him but has matured into a masterful actor who here contrives to give his character more depth than the conventional Restoration cuckold. Yes, he is drunken, loutish, cowardly and cruel, but his complaint about his wife is all too true: she doesn’t love him and never did. He is not a sympathetic figure, but his bitterness has a real foundation. Indeed, the whole play can be seen as a ruthless examination of the flaws of marriage from both male and female viewpoints. Vanbrugh, Breen and Slinger combine to make Brute a figure of horror, but also of pity: two key elements of tragedy.

Lady Brute is played by Alexandra Gilbreath, another RSC favourite. She too manages to evoke the depths of a true dilemma (for in Vanbrugh’s time there was no escaping a cruel marriage, short of degradation or death) in a role which could easily be caricature. On first entry she appears as a stock figure, but we quickly find she is more than that. I don’t think it is accidental that Slinger and Galbreath are experienced Shakespeareans. A difficulty with all Restoration comedy is that audiences may find it difficult to follow the language’s twists and turns. But with these two actors, indeed with the whole cast, the meaning is never in doubt. I don’t know the play well enough to say whether there may have been some judicious editing of the text but this production preserves its rhetorical wit and vigour without sacrificing sense.

Lady Brute’s prospective lover Constant is played by Rufus Hound, well enough and with impeccable comic timing, but this is a bravura role which in Breen’s interpretation is necessarily underplayed. Nothing to fault here, but I was more taken with John Hodgkinson as Constant’s friend Heartfree, who of all the characters begins with the most clear-eyed view of the pitfalls of marriage and yet it is he who by the end has succumbed. Vanbrugh surely intends the irony. Hodgkinson’s Heartfree is older, more dignified and less impulsive than Constant, but is drawn into the trap just the same. His stuttering romance with Lady Brute’s niece Bellinda (another fine performance, by Natalie Dew) seems to me to have more than a slight echo of Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado.

Last but not least there are Lady Fancyfull and her French maid known only as Mademoiselle. Lady Fancyfull is the target of Vanbrugh’s most obvious satire: wrongly believing herself to be admired and desired by all, she is ridiculous in herself and ridiculed for it by the other characters. Caroline Quentin makes the most of her absurdities and earns the play’s easiest laughs. Yet when she is – literally – unmasked at the end of the play, she cuts a pitiable figure.

Mademoiselle speaks many of her lines in French, reminding us of Vanbrugh’s years in France. Quite rightly the production makes no concessions to non-Francophones, and in any event her meaning is always apparent. This really is a caricature role, very funny indeed, and Sarah Twomey (another name to look out for) makes the most of it.

This is a lengthy production, three hours in total, but it never feels unnecessarily prolonged. The several musical interludes, played on-stage by an expert group of musicians in period costume, might possibly have been cut. But, as Janet said to me, this show is after all an entertainment. The words are (presumably) Vanbrugh’s own, and the music, though freshly composed by Paddy Cunneen, feels in character. Singer Rosalind Steele, playing a character aptly named Pipe (there’s that Restoration convention again) has the most beautiful voice. At one stage she is hoisted up on a swing, or something like it; pretty much the only piece of unnecessary input from the director in the whole show.

In the hands of Phillip Breen and his exceptional cast, The Provok’d Wife emerges as an important play out of its time which deserves to be better remembered not just as another Restoration comedy but for its own considerable merits. It is running at Stratford until early September, but there is as yet no sign of the transfer to London or on tour which the show undoubtedly deserves. Strongly recommended.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 26 : Silverdale

6 June 2019

To follow this walk on a map, open another tab on your browser and go to this web address: https://bit.ly/2wmwwDc. Be warned that a short section of the walk may be impassable at an exceptionally high tide.

This is one of the shortest walks yet to be listed at the Ministry, barely two miles in length, but it is full of variety and interest. There are various options to extend it; John and I would probably have done so, but for dark cloud and spotty rain which threatened to become heavier and more unpleasant at any moment. You can get an idea of the weather from John’s photographs which once again accompany this blog. Thank you, John.

The route cannot properly be described as flat. It includes one sustained climb, not a scramble but steep enough for me to need to pause several times to get my breath back. This difficulty might, however, be mitigated if you were prepared to take a longer, alternative route. We’ll come to that.

The walk starts and finishes in the pretty but sprawling village of Silverdale, north west of Carnforth in north Lancashire. On this occasion we parked roadside in Lindeth Road, just north of Lindeth Lodge Farm – look for the blue wigwam symbol in the left centre of the map. There are plenty of parking opportunities along here and on Hollins Lane nearby (for road names, expand the scale of the map by one notch).

The junction of Lindeth Road and Hollins Lane is in effect a crossroads, with an open farm entrance to the west and a continuation of Lindeth Road heading south. Follow this road, with Lindeth Tower on your right, partly hidden behind a high stone wall. The tower is not a true fortification but a Victorian folly whose main claim to fame is that the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell stayed here for a while soon after it was built.

After passing Lindeth Tower the road turns downhill, with stone walls on both sides. Soon you will come to a gate on the right hand side leading into an area of open limestone heath owned by the National Trust. A sign at the gate says Jack Scout, which appears from the map to be the name both of a headland looking out across Morecambe Bay towards Grange-over-Sands and of the heathland behind it. There surely must be an explanation for this curious name, but I have, alas, been unable to find it.

Just beyond the gate is a fine (but restored) example of an old-fashioned lime kiln, used for producing quicklime and slaked lime for use in agriculture and construction. The kiln is fenced off, but the NT has erected an informative display board. After you have examined the kiln, continue along one of the paths that lead down towards the sea. From the headland, which is very wisely protected by a wire fence, there is an excellent view which would have been even better if the sun had been out.

Several of the paths lead down to the shore, but you don’t want to do that just yet. There are no maps or signs to help find the right path, so a little trial and error may be required, but eventually you should find a path across the cliffs, possibly turning a little away from the cliff edge, until you have no other way forward but through a gate in the wall which has continued, visible or not, on your left all this way.

This is Jenny Brown’s Point, another unexplained name, though various theories have been offered (see Wiki at https://bit.ly/2WV0XyY). Leading straight out to sea here is a ridge of stones, Walduck’s Wall. It looks a bit like a jetty, but is in fact all that remains of a failed nineteenth century project to reclaim land in this corner of Morecambe Bay. Apparently the structure was hidden for decades under the shifting sands of the bay and only re-emerged in 1975. On the map it isn’t named, and is partially obscured by a line of black dots marking a boundary, but you can see it there if you look carefully.

There is a bench at Jenny Brown’s Point where you can rest and admire the view. It was rather windy when we were there, so I left my hat in the car.

Go through the gate at Jenny Brown’s Point and turn right. You are now on a narrow metalled road, but it is a cul-de-sac, in effect a private drive leading only to the buildings at Brown’s Houses. Along this road, on your left, you will find an abandoned limestone quarry where we noted a derelict railway van in which John was unreasonably interested. To me one derelict rusty van looks much like another.

The road ends at Brown’s Houses, and the residents have put up several notices making quite clear that they don’t want you walking through their front yard, so at this point you have to drop down on to the shore. This next short section of the walk may be blocked if the tide is unusually high. There is a wrecked concrete ramp, provenance unclear, which you can follow, but the next couple of hundred yards are difficult going across jagged rocks and large rough-edged stones with no obvious footing. Take care. You will need to cross these stones even if the tide is low and you venture out on to the sands.

In any event the difficult section does not extend very far and soon gives way to shingle. Here, barely above the high tide mark, is another curiosity: a tall chimney, with a small opening at its base, unconnected to any other structure. The chimney has recently been remortared by someone, possibly English Heritage – this is not a National Trust site. Local archaeologists now suggest that the chimney was part of a short-lived copper smelting operation, but no-one knows for sure, and it is an odd sight on the foreshore.

Past the chimney you are soon able to return to grassland and a clear path, with marshland to your right and partly wooded hillside to your left. After a quarter of a mile or so you come to a signpost with paths right, left and straight ahead. The right hand path leads across the marsh to a car park which is an alternative starting point for this walk, but not recommended: the approach road (visible from the train so I can vouch for this) is rough and rutted, ripe for punctures.

We took the left hand path which, as you can see from the contour lines, is a stiff climb as mentioned at the start of this blog. You could, alternatively, go straight ahead: the map shows this as a bridleway, and it crosses the contours at an oblique angle, both of which suggest it may not be so steep. The downside is that you will need to return further along a road which has some traffic. Nonetheless, if John and I do this walk again some day, we may take this alternative route.

After turning left, the climb continues for a couple of hundred yards, easing off towards the end. At the top you emerge into a meadow which we found filled with daisies and buttercups. Walk along the left hand edge of this meadow and the next, then go through a pair of gates into a muddy lane which runs straight ahead until it reaches Hollins Lane. If you want to follow in our footsteps you should turn left here, back to Lindeth Road and your parking place.

However, quite apart from the detour I have described to avoid the stiff climb, there are numerous other options for extending the walk. Look again at the map to see the network of paths which weave through and around Silverdale. One obvious option would be to cross Hollins Lane and follow the path which leads round the east side of Scout Wood, cross the next road too (Stankelt Road) and continue past the backs of the houses up to the church. From here you can either return along the road through the centre of the village or take a further detour up to Elmslack and back along the shoreline, following the Lancashire Coastal Way. As an added attraction there is a cave to be explored. I cannot guarantee the flatness of these routes, but the contours suggest any hills should be manageable.