A quiet Bank Holiday

28 May 2018

Something unusual has happened today. It is Bank Holiday Monday, and the weather has been sunny and warm. Not quite everywhere: the Guardian website has a report about a man being drowned in his motor car during flash flooding in Walsall, in the West Midlands. But here in the Lakes it has been fine.

The problem for us is that the good weather and the Bank Holiday bring out the crowds. Everywhere we go in the Lake District there will be people and motor cars. The effect is compounded by the first race meeting of the year at Cartmel which also takes place this weekend. As we know from experience, the roads around Cartmel become clogged whenever the races are on, and the effect spills back into queues on the roads in Cark and Grange. So we had to think carefully about where we would spend our afternoon.

A couple of days ago we drove north through Grizedale to Hawkshead, and on the way noticed signs for the gardens at Graythwaite Hall. The name, and the signs, were new to me. I collect all the tourist leaflets for the Lakes that I can lay my hands on, but I had never seen any for Graythwaite. So we thought we would investigate.

A couple of days ago we drove north through Grizedale to Hawkshead, and on the way noticed signs for the gardens at Graythwaite Hall. The name, and the signs, were new to me. I collect all the tourist leaflets for the Lakes that I can lay my hands on, but I had never seen any for Graythwaite. So we thought we would investigate.

Turning through the gates and down a gravel drive, we found a small car park with an honesty box for admission charges – £4 each. Next to the honesty box was a tray containing a pile of information leaflets, a single side of A4, telling the story of the estate. The Hall was built in the 1600s and modernised twice in the 1800s; the gardens were laid out in Victorian times. The owners since the Hall was first built have been the Sandys family, one of whose early members became the Archbishop of York and was the founder of Hawkshead School. Tree plantings and ornamental ironwork in the gardens celebrate important dates in the family history.

There were perhaps five other vehicles in the car park and at least one of them looked as if it belonged to the estate. As we wandered around the gardens, we met no-one else. Literally no-one. Graythwaite must be one of the Lake District’s best kept secrets, because the gardens are really beautiful, at least at this time of year when the rhododendrons and other flowering shrubs are in bloom. There was a riot of colour in every direction. The lawns are well kept and visitors are encouraged to walk across them – no need to keep to marked paths.

There were perhaps five other vehicles in the car park and at least one of them looked as if it belonged to the estate. As we wandered around the gardens, we met no-one else. Literally no-one. Graythwaite must be one of the Lake District’s best kept secrets, because the gardens are really beautiful, at least at this time of year when the rhododendrons and other flowering shrubs are in bloom. There was a riot of colour in every direction. The lawns are well kept and visitors are encouraged to walk across them – no need to keep to marked paths.

There are also a stream and a small pond, and John indulged one of his usual pursuits, spending ten minutes or more trying to get a decent photograph of the dragonflies which we spotted flitting over the foliage at the water’s edge. With camera in hand he can be very patient and persistent. This photo is not really one of his best efforts; the dragonflies today were just too elusive.

There are also a stream and a small pond, and John indulged one of his usual pursuits, spending ten minutes or more trying to get a decent photograph of the dragonflies which we spotted flitting over the foliage at the water’s edge. With camera in hand he can be very patient and persistent. This photo is not really one of his best efforts; the dragonflies today were just too elusive.

A few days ago I was at Kew Gardens with Georgina, admiring the azaleas which are in bloom there. John and I have visited Muncaster Castle, near Ravenglass on the Cumbria coast, on several previous occasions at this time of year in order to see the rhododendrons and azaleas in flower. But Graythwaite is every bit as good as either of these – smaller, but just as colourful. And of course the beauty is enhanced by the lack of noise from other visitors. There is bird song, the hum of insects and (if you listen really carefully) the ripple of water, but otherwise… quiet. This is how it must have been for generations of the Sandys family. What a privilege.

Graythwaite Hall itself is off limits, and judging from the open first-floor windows I should guess that someone from the family is in residence. But we could admire it from a distance. The building does certainly have the appearance of a well-proportioned Victorian country house, but apparently behind the façade much of the original sixteenth century building is still in place. Perhaps one day the Hall, as well as the gardens, will be opened to visitors. Though if the place becomes too popular it will lose some of its charm.

Graythwaite Hall itself is off limits, and judging from the open first-floor windows I should guess that someone from the family is in residence. But we could admire it from a distance. The building does certainly have the appearance of a well-proportioned Victorian country house, but apparently behind the façade much of the original sixteenth century building is still in place. Perhaps one day the Hall, as well as the gardens, will be opened to visitors. Though if the place becomes too popular it will lose some of its charm.

From Graythwaite we drove north and stopped in a car park on the edge of Esthwaite Water. This was another novelty. Esthwaite runs between, and parallel to, Windermere and Lake Coniston, but ever since I can remember it has been closed to the public. You could see the lake from the roads on either side, or from the fells above, but not go down to the water’s edge. That has now changed.

Near the car park some information boards had been erected, from which I learned that Esthwaite is privately owned under a lease which has recently changed hands. Apparently (as I discovered later, online) the lease was sold in 2013 through a listing on eBay, which must be a first of some kind. Its particular value lay in the well established (and well-known) trout fishery which the previous owner had developed over the last 32 years.

Near the car park some information boards had been erected, from which I learned that Esthwaite is privately owned under a lease which has recently changed hands. Apparently (as I discovered later, online) the lease was sold in 2013 through a listing on eBay, which must be a first of some kind. Its particular value lay in the well established (and well-known) trout fishery which the previous owner had developed over the last 32 years.

The new owners have evidently decided to see if they can make a bit more of their new possession. So as well as the trout fishery, there are now a car park, a picnic area, a café (with excellent cake) and a jetty with rowing boats for hire. Most of the lake shores are still closed off, but perhaps they will get round to constructing a lakeside path. At present you have to use the road, which isn’t much fun and is mostly not at all close to the water.

I had always understood Esthwaite was a shallow, reedy mere. There are certainly reeds, but the depth reaches 45 feet, which makes it a true lake and not just a fen. In fact it looks rather like Windermere, with sloping green banks running down to the shore, but without Windermere’s boats, lake steamers, windsurfers and water skiers. It is also (for the present) a haven for wild life: there are otters, and grebes, and a small colony of osprey, not to mention various rare plants, and of course lots of ducks. In the café we found a screen showing a live feed from a camera fixed above an osprey nest, and in the nest a small clutch of eggs were sometimes visible.

I had always understood Esthwaite was a shallow, reedy mere. There are certainly reeds, but the depth reaches 45 feet, which makes it a true lake and not just a fen. In fact it looks rather like Windermere, with sloping green banks running down to the shore, but without Windermere’s boats, lake steamers, windsurfers and water skiers. It is also (for the present) a haven for wild life: there are otters, and grebes, and a small colony of osprey, not to mention various rare plants, and of course lots of ducks. In the café we found a screen showing a live feed from a camera fixed above an osprey nest, and in the nest a small clutch of eggs were sometimes visible.

Truth to tell, I have slightly mixed feelings about Esthwaite. I am glad that we now have access to a lake that has previously been closed off; but, as with Graythwaite, there is a risk that greater public access will destroy some of the charm, and at Esthwaite may also endanger the wildlife and environment. The new owners will have to strike a careful balance.

We drove home from Esthwaite by a different route so as to avoid the race traffic. All told we had succeeded beyond expectation in enjoying a quiet Bank Holiday.

The aerial photograph of Esthwaite was taken from the Visit Cumbria website. All the other photographs are by John. Many thanks to him as always.

——————–

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 11 : Sandscale

27 May 2018

To follow this walk on a map, open another tab on your browser and input this address: https://bit.ly/2sjDq9E.

To follow this walk on a map, open another tab on your browser and input this address: https://bit.ly/2sjDq9E.

This is another very flat walk, around a low lying headland just north of Barrow-in-Furness and on the other side of the Duddon Estuary from Hodbarrow which was the subject of my previous blog. John and I ventured on this walk earlier today and, truth to tell, the conditions weren’t ideal: the sun was out and it was warm, but also quite windy, and I was worried that sand might get in John’s sore eye, which is recovering from minor laser surgery. However, he seems to have escaped unscathed.

I parked the car on a bare roadside patch just outside the National Trust’s car park (at the top of the map, right centre). While John’s eye recovers I have been our driver, and John has belaboured me for my unfamiliarity with the controls, especially the gears, of his car. There is in fact quite a noticeable difference in the feel of the gears between John’s Volkswagen Polo and my own Toyota Corolla, and it is some years now since I drove the Polo at all regularly, so I think I have a reasonable excuse. But John, of course, will have none of it.

Anyway. I have visited Sandscale only once before, although I think John has also been there once or twice on his own, and was interested to see how the National Trust has been investing in the site. There is now a proper car park (free to members, ha ha!) and a brick “welcome hut” with a warden. But I think they will need to extend the car park soon; it was full when we arrived, and there were cars parked along the approach road for some distance.

We walked down through the dunes to the shoreline. The gusty wind was strong enough to be picking loose sand off the dunes and whipping it across the shore – not at all ideal for someone with a sore eye needing protection. I can just remember a family holiday from when I was no more than five years old, at Marske on the North Yorkshire coast between Redcar and Saltburn. It was supposedly a beach holiday, but as a little boy the sand whipped up by the North Sea winds stung my unprotected legs unmercifully. We had to drive fifteen miles round the coast to Scarborough to find beaches which were comfortable for me to play on.

We walked down through the dunes to the shoreline. The gusty wind was strong enough to be picking loose sand off the dunes and whipping it across the shore – not at all ideal for someone with a sore eye needing protection. I can just remember a family holiday from when I was no more than five years old, at Marske on the North Yorkshire coast between Redcar and Saltburn. It was supposedly a beach holiday, but as a little boy the sand whipped up by the North Sea winds stung my unprotected legs unmercifully. We had to drive fifteen miles round the coast to Scarborough to find beaches which were comfortable for me to play on.

I don’t think Sandscale today was as bad as Marske; of course I am no longer a little boy, and have given up wearing shorts out of consideration for the public. But my memory of Marske is that the onslaught was constant, where today it was more fitful. There were children playing quite happily on and near the beach, not apparently at all troubled by the stinging sand. Perhaps they just grow up tougher these days.

The tide today was out and it was easy to imagine you might be able to walk right across the sands to Hodbarrow – no more than a couple of miles as the crow flies. In fact I think it would be a tricky thing to do: the channel of the River Duddon was invisible from the shoreline, but it must have been there somewhere, and even at low tide I suspect you would need boots, if not a bathing costume, to make the crossing. The sands were completely bare, and John and I were each independently put in mind of one of our favourite poems (and one of the greatest in the English language), Shelley’s Ozymandias, and its final line: “the lone and level sands stretch far away.” Shelley’s sands were mid-desert, not mid-estuary, but there was something about today’s scene that seemed very remote and empty.

The tide today was out and it was easy to imagine you might be able to walk right across the sands to Hodbarrow – no more than a couple of miles as the crow flies. In fact I think it would be a tricky thing to do: the channel of the River Duddon was invisible from the shoreline, but it must have been there somewhere, and even at low tide I suspect you would need boots, if not a bathing costume, to make the crossing. The sands were completely bare, and John and I were each independently put in mind of one of our favourite poems (and one of the greatest in the English language), Shelley’s Ozymandias, and its final line: “the lone and level sands stretch far away.” Shelley’s sands were mid-desert, not mid-estuary, but there was something about today’s scene that seemed very remote and empty.

Looking across the estuary you can see the little town of Millom and, beyond it, the dark smooth-topped lump that is Black Combe, most westerly of the Lake District mountains. Black Combe isn’t all that well known. It’s not a very interesting or characterful mountain, lacking a clearly defined peak or any fell paths for intrepid walkers to follow, but it has become very familiar to us over the years.

Our plan today was to follow the shoreline round, west and then south, then cut back on one of the tracks across the dunes to our starting point. This should have been a fairly straightforward proposition, apart from the wind: but we ran into a couple of other problems, and if you follow our footsteps you should be prepared for them.

First, each footstep sank a little into the soft, yielding sands: not just on the dry sand of the dunes, but also on the upper foreshore, and in some places almost down to the waterline. It’s fun for a while to leave your footsteps impermanently printed on previously virgin sands, but after a while you find your feet start to drag. The extra effort required each time to lift your foot clear of the sand is trivial, but the cumulative effect is surprisingly tiring. John’s endurance is much greater than mine but he too confessed that this walk was harder work than he had imagined. So: just because it’s flat, don’t think it will be easy.

Second, as we made our way along the shore we started to get worried about the way back. Near the car park, the dunes are relatively low and there are paths cutting through them to the shoreline. But by the time you get half a mile along the shoreline, the dunes are high and, if not quite impenetrable, at least a formidable barrier. For more than a mile we could see no sign of any paths. We knew there must be some kind of approach road: ahead of us someone had brought a motor vehicle down to the beach (we never got close enough to see exactly what it was). But it is still a test of faith to carry on when you can see no way out.

Eventually, however, we came to an area of shingle – you can see it clearly on the map, in the bottom left hand corner just above Lowsy Point. Just here (but not shown on the map) a stony track climbs up a short way through the dunes to a gate. We thankfully climbed up to the gate, and found something like a farm track winding through the dunes in approximately the direction we wanted to go.

Eventually, however, we came to an area of shingle – you can see it clearly on the map, in the bottom left hand corner just above Lowsy Point. Just here (but not shown on the map) a stony track climbs up a short way through the dunes to a gate. We thankfully climbed up to the gate, and found something like a farm track winding through the dunes in approximately the direction we wanted to go.

Soon enough this track fed into a gravelled lane. We spotted a stile across a fence on our left side which I now think may have led to the path marked on the map (green dots), but this was not clear to us at the time and we did not want to find ourselves stranded in mid-dunes.  Instead, we followed the gravelled lane a little further and soon enough it turned inland, near a wartime pillbox. Were they really expecting invasion forces to arrive on this beach? Surely not.

Instead, we followed the gravelled lane a little further and soon enough it turned inland, near a wartime pillbox. Were they really expecting invasion forces to arrive on this beach? Surely not.

After a short distance the lane comes to a fence with a gate and stile to the left while the continues to the right. On a post next to the stile is one of the National Trust’s waymarkers. You cross the stile and follow the track alongside the fence. A short way further you will find earthworks and bits of stonework, which with a little effort you can identify as the remains of a mineral railway which once crossed the dunes here to a long-defunct mine.  Presumably iron ore, the same as Hodbarrow on the other side of the estuary. John was fascinated by these relics, though there is little enough to see.

Presumably iron ore, the same as Hodbarrow on the other side of the estuary. John was fascinated by these relics, though there is little enough to see.

The rest of the walk is easy, and we found it the most pleasant part of the day, as we were partly out of the wind and wholly away from the swirling sands. Just follow this farm track until you reach the metalled road, turn left and follow the road back to the car park. I estimate the whole walk is barely four miles long, but the extra effort of crossing the yielding sands made it feel longer than that. We took about two and a quarter hours.

Thanks to John for the photographs.

——————–

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 10 : Hodbarrow

6 May 2018

To follow this walk on a map, open another tab on your browser and input this address: https://bit.ly/2KDIU7A.

Some of the walks in this series only be described as flat with a good deal of poetic licence. But not this one. It involves walking around a freshwater lagoon created on the site of a former iron ore mine. If this sounds less than thrilling, don’t be deceived. The lagoon itself is a bird sanctuary where various rare species can be found. On a clear day the views, both over Morecambe Bay and back towards Black Combe and the heart of the Lake District, are stunning. Offshore a vast array of wind farms lines the horizon (you may need to enlarge the photo to see them clearly). And the walk really is flat: I doubt if there is a rise and fall of more than 5 metres all the way round unless you go out of your way. Its length is about three and a half miles, mostly on paths or byways with little vehicular traffic.

Some of the walks in this series only be described as flat with a good deal of poetic licence. But not this one. It involves walking around a freshwater lagoon created on the site of a former iron ore mine. If this sounds less than thrilling, don’t be deceived. The lagoon itself is a bird sanctuary where various rare species can be found. On a clear day the views, both over Morecambe Bay and back towards Black Combe and the heart of the Lake District, are stunning. Offshore a vast array of wind farms lines the horizon (you may need to enlarge the photo to see them clearly). And the walk really is flat: I doubt if there is a rise and fall of more than 5 metres all the way round unless you go out of your way. Its length is about three and a half miles, mostly on paths or byways with little vehicular traffic.

The mine at Hodbarrow produced some of the highest quality iron ore anywhere in the world, and remained in operation until 1968. The nearby town of Millom owes its existence almost entirely to the mining industry, and since the closure of the mine has been an unemployment black spot. I remember visiting with Mum and Dad in the early 1970s; it felt like somewhere out of the Industrial Revolution brought forward to our own times. Millom’s fortunes have risen a little since then, not least thanks to the opportunities for holidaymakers around the lagoon, but I still find it one of the less attractive places on the edge of the Lakes, and you will probably not want to linger in the town.

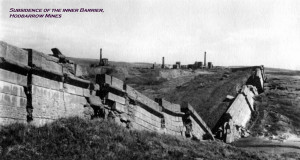

Although the mines were rich, flooding was a constant problem throughout their existence, both from the tide and from seepage into the workings. Constant pumping was necessary, but the quality of the ore made the effort worth while. To alleviate the threat from tidal waters, two great stone barriers were built. The first, the Inner Barrier, was completed in 1890, but some productive veins of ore extended beyond it and so a second, the Outer Barrier, was constructed in 1904. The Inner Barrier was then allowed to collapse into the mine workings. You can still see the surviving sections of the Inner Barrier, surrounded by the waters of the lagoon. The Outer Barrier now forms the lagoon’s outer wall.

Today has been an exceptionally clear, warm day and John and I decided to venture on this walk. As it is a Bank Holiday weekend, we thought the main centres in the Lake District would be heaving with holidaymakers. We preferred a slightly out-of-the-way destination; and scarcely anywhere is more out of the way than this corner of West Cumbria.

We drove through Millom to Haverigg, turned left at the little roundabout in the centre of the village, and parked in one of several free parking areas. I can remember Haverigg from visits in the 1970s. A stream, named on the map as the Haverigg Pool, runs down through the village, and there was an ancient rusting aero engine on the shoreline just where the stream flows into the bay. Dad and David were fascinated by this relic. But Haverigg then was that kind of place, where lumps of scrap metal could be found just lying around.

What a contrast today. The whole area has been cleaned up. Many of the older buildings have been renovated and are now offered as holiday lets. Just to the east of the village, near where we parked our car, is an extensive holiday site with dozens of the pale-green static caravans that I have mentioned before in these blogs. The attraction here is not just the Lake District, but the beach (some people are easily pleased) and the water sports now available on the lagoon. HM Prison Haverigg is probably still the largest local employer, but services for holidaymakers are bringing in much-needed new income.

From the car park we walked across to the start of the Outer Barrier, along which there is now a broad path, and followed it all the way round to Hodbarrow Point. About half way along is an old iron lighthouse which I find rather sad. The lighthouse was constructed in 1904 and operated until 1949. It was then derelict until 2004 when it was renovated as part of a community project, promoted by a local school and supported with lottery money. Unfortunately it now once again appears derelict. All the glass panes have gone, the entrance door is rusted and padlocked, and the whole structure has been badly corroded by salt spray and sea air. Evidently the renovators didn’t consider future maintenance.

Near the lighthouse is a short path leading to a low concrete structure, a hide from which the bird life on the lagoon can be observed. Neither John nor I have much knowledge of birds, but today there was a real rarity which even we couldn’t miss, a black swan. According to the RSPB: “black swans are native to Australia … brought to the UK as ornamental birds like peacocks and golden pheasants. Like many other captive birds, they occasionally find their way out into the wild….There have been occasional reports of successful breeding attempts in the UK but they have not become established.” So it seems likely that our black swan was an escaped prisoner.

Near the lighthouse is a short path leading to a low concrete structure, a hide from which the bird life on the lagoon can be observed. Neither John nor I have much knowledge of birds, but today there was a real rarity which even we couldn’t miss, a black swan. According to the RSPB: “black swans are native to Australia … brought to the UK as ornamental birds like peacocks and golden pheasants. Like many other captive birds, they occasionally find their way out into the wild….There have been occasional reports of successful breeding attempts in the UK but they have not become established.” So it seems likely that our black swan was an escaped prisoner.

As you can see on the map, from Hodbarrow Point you can follow various paths onwards. We turned left, along a gravel track which passes a second derelict lighthouse, built of stone. This was the original structure built to guide shipping up to the wharf, bringing in coal to operate the pumping engines and take away excavated ore, but it became redundant when the Outer Barrier was completed. It has, however, weathered a lot better than the new lighthouse. The path then passes through a grassy meadow and John had been hoping to spot some butterflies which are said to be abundant here, but only one was to be seen, flying rapidly away from us. I suspect that they are suspicious of the sudden change in the weather and are not yet ready to emerge from their chrysalises.

As you can see on the map, from Hodbarrow Point you can follow various paths onwards. We turned left, along a gravel track which passes a second derelict lighthouse, built of stone. This was the original structure built to guide shipping up to the wharf, bringing in coal to operate the pumping engines and take away excavated ore, but it became redundant when the Outer Barrier was completed. It has, however, weathered a lot better than the new lighthouse. The path then passes through a grassy meadow and John had been hoping to spot some butterflies which are said to be abundant here, but only one was to be seen, flying rapidly away from us. I suspect that they are suspicious of the sudden change in the weather and are not yet ready to emerge from their chrysalises.

The path eventually joins a paved road near the entrance to the old quarry, marked on the map, which now appears to be in use as a council waste dump. A right turn here leads up towards Millom, but you should bear left, following a narrower paved lane which curves to the left and into the caravan site. This appears to be a public area, you can walk alongside or among the caravans, keeping the lagoon in sight to your left, and so back to the car park.

After our walk was over we had some time to spare, so we drove a few miles up the coast to Silecroft, where John, David and I all used to play on the beach when we were children. It was about half an hour’s drive from Woodgate and a favourite destination. Today Silecroft has not much changed except for the welcome addition of a café in a prefabricated hut which looks like another static caravan, painted white and adapted for the purpose. We each had a mug of tea and John walked down to the waterline. There is a wide, sloping band of shingle which drops down to the beach and the incoming tide had just covered the sands when we arrived. This shingle was, and is, Silecroft’s one disadvantage: we watched one little girl struggling barefoot up across the pebbles, and eventually being rescued by her mother.

After our walk was over we had some time to spare, so we drove a few miles up the coast to Silecroft, where John, David and I all used to play on the beach when we were children. It was about half an hour’s drive from Woodgate and a favourite destination. Today Silecroft has not much changed except for the welcome addition of a café in a prefabricated hut which looks like another static caravan, painted white and adapted for the purpose. We each had a mug of tea and John walked down to the waterline. There is a wide, sloping band of shingle which drops down to the beach and the incoming tide had just covered the sands when we arrived. This shingle was, and is, Silecroft’s one disadvantage: we watched one little girl struggling barefoot up across the pebbles, and eventually being rescued by her mother.

John did a little beachcombing, threw a few stones into the sea to make a splash, and came back with three smooth white pebbles. I sat on one of the wooden benches by the top of the shingle and watched the sparkling light as the sun, declining towards the horizon, reflected off the incoming waves. It was that kind of afternoon.

Thank you to John for the photographs he provided for this blog. Much gto John’s disgust, I have also used a couple of pictures from a photoblog by Jo Sweeney which is well worth a look: http://josweeney.net/haverigg-and-hodbarrow-nature-reserve. I found the picture of Silecroft on Google.

——————–

Some day my prints will come

5 May 2018

John and I are back in the Lake District again, for the May Day bank holiday weekend. I came up on the train from Oxted, via London and Lancaster, on Thursday; John drove here from Manchester on Friday evening. This morning (Saturday), as usual, we went in to Ulverston to buy supplies.

While we were shopping, John picked up a publicity leaflet about an event taking place this weekend at Ulverston’s Coronation Hall: Printfest 2018, which describes itself as the UK’s foremost artist-led printmaking festival. John’s artistic nose twitched at once. A couple of years ago I would probably not have been interested, but the Hokusai exhibition which we went to at the British Museum last year (see my blog on 16 July 2017) has made me aware of what can be achieved in printmaking, and also given me a very basic understanding of the artistic processes behind it. We didn’t have any better plans for the morning, so off we went to the Coronation Hall. And I am ever so glad that we did.

We paid £5 each for entry, in return for which we got the opportunity to vote for the Visitors’ Prize, awarded to the printmaker receiving the most votes, and to enter the raffle (40 prizes: choose from a selection of prints donated by the exhibitors). I don’t usually care about raffles, but this is one I should really like to win.

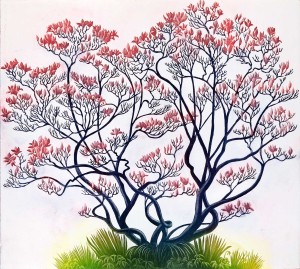

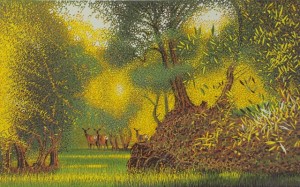

The very first exhibit gave us a flavour of what was on offer. The artist was Morna Rhys and I have posted here a couple of examples. So far as I can tell there is nothing especially new or innovative about her work except that she uses a copper plate, which can’t be cheap, to make her etchings. But I thought the results absolutely stunning. My Magnificent Magnolia is strongly reminiscent of Japanese prints, and Into the Sunlight of one of my favourite painters, Henri Rousseau.

You can see a wider range of examples of Rhys’s work at http://www.mornarhys.co.uk/gallery. The style is fairly consistent, but compared to other exhibitors her range of subjects is much wider. I may as well say that after we had been round the whole exhibition she got my vote.

I cannot possibly write about every one of the 49 exhibitors; we did not have time to stand and admire them all, but as we walked round stopped to look more closely at those which caught our eyes. We did find, though, that our tastes overlapped quite strongly.

John’s favourite, for whom he cast his vote, was Carol Nunan. We both liked her picture Under Celestial Skies (not a great title – celestial and skies mean more or less the same thing; but never mind). There is a greater degree of abstraction in this picture, and in her other prints on display, than in Rhys’ work, but the colours are stunning. Nunan, and many of the exhibitors, uses a technique new to me called collagraphy, a portmanteau word combining collage and lithography. When preparing to make a print, objects like leaves or textiles are affixed to the printing plate before it is inked. As she explained to us, there are limits to the depth of the collage, and the paper or card on which the print is made has to be soft and thick enough to receive the imprint, but the results are worth the effort, as you can see in the fine detail of the leaf in this picture.

Unfortunately her website (http://carolnunan.co.uk) doesn’t include a full gallery of pictures, only a selected few. I thought some of her prints were straining a little too hard for effect but John didn’t seem to be bothered by this.

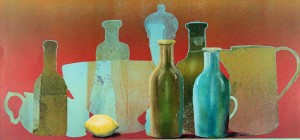

One who caught my eye more than John’s was Sarah du Feu (http://www.sarahdufeu.co.uk) who exhibited both semi-abstract landscapes and stylized still lifes. I didn’t care much for the landscapes: their colours are striking, but being on the edge of abstraction seemed to me neither one thing nor the other. However I really liked the still lifes, very reminiscent of two of Dad’s oil paintings which hang on my kitchen wall. By comparison with Rhys, though, du Feu’s work seemed to me very repetitive, as if striving over and over again for the perfect realisation of a relatively few ideas.

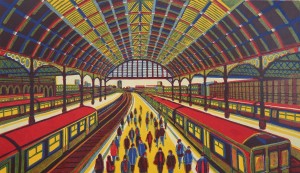

The range of styles and techniques on display was fascinating. Among the most striking pictures on display were a set of linocuts made by Gail Brodholt, named Printmaker of the Year 2018 (I have no idea how great a distinction this is, but it sounds good). Linocuts are just what they sound like: the same principle as woodcuts, but using linoleum instead of wood. These prints are remarkable for their bold stylized draughtsmanship and colours, which really stood out among the other exhibits, and of course we noticed them because they include so many railway pictures. However, I am not sure that I would want any of them on my dining-room wall: they are just a bit too bold and attention-seeking. Brodholt’s website is easily accessible (http://www.gailbrodholt.com). She makes paintings as well as linocuts in a very similar style.

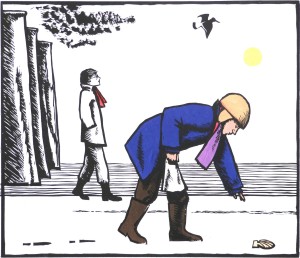

One or two of the exhibitors displayed one outstanding work among others that left me unmoved. This applied most obviously to Frans Wesselman, whose woodcut Beach, simply drawn and coloured, has a character and wit which were absent from most of the exhibition. Thinking about it, there were not many representations of human figures on display at all, except a few in highly stylized forms, which made this one stand out. I was, however, unmoved by the rest of Wesselman’s work, most of which struck me as either uninspired or slightly contrived. See for yourself at http://www.fwstainedglass.com/portfolio/printmaking.

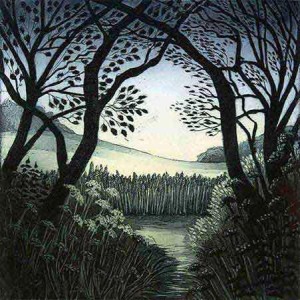

Of all the artists on display, the one whose work John and I would both certainly have on our living-room walls was Mark Pearce. His prints are beautifully drawn (linocuts again), most of them decorative landscapes in which colour is cleverly used to intensify the image. Pearce is another artist who makes paintings as well as prints, as you can see from his website (http://www.markapearce.co.uk/gallery). You might possibly regard the paintings as slightly kitschy, but it is hard to think that of the linocuts, so well are they executed. Achieving these effects by cutting precise lines into a sheet of linoleum and printing from it, over and over again, to obtain the range of colour is a remarkable exhibition of craftsmanship and skill.

We didn’t however buy any of his pictures, or anything else from the exhibition apart from a handful of greetings cards. Even the smallest prints, unframed, by less well established artists like Rhys and du Feu carried prices in excess of £100. Pearce’s larger prints were close to £1000 each. Printfest is billed as offering affordable art for all, but I guess it depends on your idea of affordability.

We enjoyed the exhibition. It has been a regular event in Ulverston every year since 2001 and this year’s was the largest yet. The Coronation Hall was crowded, and the artists must have had mixed feelings about this: it’s great that there should be so much interest in their work, but it will not be seen to best effect if the crowding becomes too severe. Obviously Printfest is a great event for Ulverston (all the car parks were full, and there must be spinoff benefits for local businesses) but they need to find more space from somewhere.

We shall certainly be back next year.

——————–

The great, the good and the favourites (2)

4 May 2018

According to the Guardian (https://bit.ly/2liiqw2), more books are published per capita in the UK than in any other country in the world. In fact more titles are published here each year (184,000 in 2013) than in any other country except the USA and China: so many that it is hard to imagine how we manage to read them all. Perhaps the delusion is more common than I had realised that, if I buy a book and put it on my shelves, somehow its contents will seep into my consciousness without any further effort on my part.

The Guardian story is four years old, but there’s no reason to think things have changed. Unfortunately it is not such good news as you might imagine. How are we to separate gold from dross? And how is the gold to survive against such relentless competition? It is easy to say that gold shines through; there seems to be an awful lot of fool’s gold in circulation.

Take, for instance, Lee Child. I like his books, but no-one could mistake them for great literature. Probably in 30 years’ time they will be found only in second-hand bookshops, and in a hundred years’ time only with difficulty. Child’s 21 novels to date all feature tough guy Jack Reacher who wanders around the United States righting wrongs, and they are all multi-million bestsellers, despite the fact that Child essentially writes the same book over and over again, with superficial and contextual variations. Indeed he has summarised his template plot himself: “Somebody does a very bad thing, and Reacher takes revenge.” This is not to belittle Child, who is a skilful, efficient writer in his genre. You can read the books in more or less any order, but I suggest you start with the first to be published, Killing Floor, which is also one of the best.

Take, for instance, Lee Child. I like his books, but no-one could mistake them for great literature. Probably in 30 years’ time they will be found only in second-hand bookshops, and in a hundred years’ time only with difficulty. Child’s 21 novels to date all feature tough guy Jack Reacher who wanders around the United States righting wrongs, and they are all multi-million bestsellers, despite the fact that Child essentially writes the same book over and over again, with superficial and contextual variations. Indeed he has summarised his template plot himself: “Somebody does a very bad thing, and Reacher takes revenge.” This is not to belittle Child, who is a skilful, efficient writer in his genre. You can read the books in more or less any order, but I suggest you start with the first to be published, Killing Floor, which is also one of the best.

Child’s books are boiled down to essentials, but some crime and thriller writers aim a little higher. I’ve written elsewhere about Michael Gilbert, who achieves a surprising variety within the genre, and about Michael Malone’s book Time’s Witness, which applies genre trappings to a novel with higher ambitions. Another whom I like is the American Robert Crais, who writes hard-boiled private eye stories which combine graphic violence with neat characterisation and some sensitivity. His leading character, Elvis Cole, is a worthy successor to Philip Marlowe: not everything goes his way, and he struggles to make sense of a morally compromised world. With Crais it is a good idea to read the books in their proper sequence, starting with The Monkey’s Raincoat. Raymond Chandler died in 1959 and we still read his books; Crais is good enough for his books also to survive, but the field is crowded with inferior imitations.

Child’s books are boiled down to essentials, but some crime and thriller writers aim a little higher. I’ve written elsewhere about Michael Gilbert, who achieves a surprising variety within the genre, and about Michael Malone’s book Time’s Witness, which applies genre trappings to a novel with higher ambitions. Another whom I like is the American Robert Crais, who writes hard-boiled private eye stories which combine graphic violence with neat characterisation and some sensitivity. His leading character, Elvis Cole, is a worthy successor to Philip Marlowe: not everything goes his way, and he struggles to make sense of a morally compromised world. With Crais it is a good idea to read the books in their proper sequence, starting with The Monkey’s Raincoat. Raymond Chandler died in 1959 and we still read his books; Crais is good enough for his books also to survive, but the field is crowded with inferior imitations.

Chandler wrote an essay The Simple Art of Murder in which he is very severe on the classic British detective story as written by Agatha Christie and others. I share his disdain for Christie, who occupies a dismaying amount of shelf space even in the modern bookshop, but I find it hard that he brackets Christie with my favourite writer of detective stories (after Conan Doyle), Dorothy Sayers. It’s true that Sayers’ early books are formulaic, and her protagonist Lord Peter Wimsey an insensitive (if brilliant) snob. But she improved over time, and The Nine Tailors, Murder Must Advertise and Have His Carcase are well worked-out stories in which the background and the minor characters are fully developed, as if these were “proper” novels. The nub of Chandler’s criticism is that the real world is nothing like what the classic detective story portrays: in real life the crimes are more mundane, the police more diligent, the independent amateur has no place. In these three books Sayers refutes Chandler.

Chandler wrote an essay The Simple Art of Murder in which he is very severe on the classic British detective story as written by Agatha Christie and others. I share his disdain for Christie, who occupies a dismaying amount of shelf space even in the modern bookshop, but I find it hard that he brackets Christie with my favourite writer of detective stories (after Conan Doyle), Dorothy Sayers. It’s true that Sayers’ early books are formulaic, and her protagonist Lord Peter Wimsey an insensitive (if brilliant) snob. But she improved over time, and The Nine Tailors, Murder Must Advertise and Have His Carcase are well worked-out stories in which the background and the minor characters are fully developed, as if these were “proper” novels. The nub of Chandler’s criticism is that the real world is nothing like what the classic detective story portrays: in real life the crimes are more mundane, the police more diligent, the independent amateur has no place. In these three books Sayers refutes Chandler.

Crime fiction must account for a good proportion of those 184,000 books. Most of it is rubbish, far inferior to Chandler or Crais or Sayers, but I should mention a couple of others. Graham Hurley wrote a series of police procedural novels based in Portsmouth, starting with Turnstone and culminating with Happy Days, which completed the story of his central character, DI Joe Faraday. The novels are notable for their downbeat tone. Faraday struggles against overwork, lack of resources, police bureaucracy and a neglected underclass who feel they owe nothing to society and behave accordingly. The books are not just crime stories, but a portrait – indeed, a horribly plausible indictment – of a society that is breaking down. It is a mystery to me that they aren’t better known, and a gross injustice that Hurley now struggles to find a place on the shelves in the bookshops. Or perhaps it’s not such a mystery: few readers want their fiction to be so depressing.

Crime fiction must account for a good proportion of those 184,000 books. Most of it is rubbish, far inferior to Chandler or Crais or Sayers, but I should mention a couple of others. Graham Hurley wrote a series of police procedural novels based in Portsmouth, starting with Turnstone and culminating with Happy Days, which completed the story of his central character, DI Joe Faraday. The novels are notable for their downbeat tone. Faraday struggles against overwork, lack of resources, police bureaucracy and a neglected underclass who feel they owe nothing to society and behave accordingly. The books are not just crime stories, but a portrait – indeed, a horribly plausible indictment – of a society that is breaking down. It is a mystery to me that they aren’t better known, and a gross injustice that Hurley now struggles to find a place on the shelves in the bookshops. Or perhaps it’s not such a mystery: few readers want their fiction to be so depressing.

And finally in this genre, C J Sansom, who has been writing a series of crime novels set in Tudor times. His protagonist is Matthew Shardlake, a hunchback lawyer who has some of Marlowe’s qualities, seeking to do the right thing at a time when the law was often corrupt. Sansom underpins his stories of crime and detection with historical authenticity and effective characterisation. This is another series that you should read in sequence, starting with Dissolution, though the best to date is probably the third, Sovereign. Sansom, like Child, has numerous inferior imitators; accept no substitute.

And finally in this genre, C J Sansom, who has been writing a series of crime novels set in Tudor times. His protagonist is Matthew Shardlake, a hunchback lawyer who has some of Marlowe’s qualities, seeking to do the right thing at a time when the law was often corrupt. Sansom underpins his stories of crime and detection with historical authenticity and effective characterisation. This is another series that you should read in sequence, starting with Dissolution, though the best to date is probably the third, Sovereign. Sansom, like Child, has numerous inferior imitators; accept no substitute.

Sansom creates a dilemma for bookshops: are his books crime fiction, historical fiction, or just plain fiction? It matters because crime fiction usually has its own shelves and is still regarded by critics as a kind of ghetto where only inferior work can be found. This kind of class distinction is, of course, ridiculous… but it’s also necessary, because while some crime novels address serious themes and attempt literature, far more are just potboilers. And that is what most of the punters in the bookshops are looking for. The same applies to science fiction and fantasy, about which I have in mind (eventually) to write a separate blog. So my favourite SFF books will not appear here today.

Historical fiction is another matter. The booksellers’ consensus is, apparently, that historical novels can be serious fiction. They are shelved (and, mostly, reviewed) accordingly. In fact much historical fiction is at least as ephemeral as Lee Child; but no matter, at the other end of the scale we have Hilary Mantel, whose two Cromwell novels, Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies, are among the best books published in the last ten years. The third, which will describe Thomas Cromwell’s downfall, is eagerly awaited. Are these great fiction? It’s too soon to tell, but they tell a great story with subtlety and intelligence, and create compelling portraits not just of Cromwell but of Henry VIII and his court. Mantel is an interesting novelist who doesn’t repeat herself, but nothing else she has written has enjoyed a fraction of these two books’ success.

Historical fiction is another matter. The booksellers’ consensus is, apparently, that historical novels can be serious fiction. They are shelved (and, mostly, reviewed) accordingly. In fact much historical fiction is at least as ephemeral as Lee Child; but no matter, at the other end of the scale we have Hilary Mantel, whose two Cromwell novels, Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies, are among the best books published in the last ten years. The third, which will describe Thomas Cromwell’s downfall, is eagerly awaited. Are these great fiction? It’s too soon to tell, but they tell a great story with subtlety and intelligence, and create compelling portraits not just of Cromwell but of Henry VIII and his court. Mantel is an interesting novelist who doesn’t repeat herself, but nothing else she has written has enjoyed a fraction of these two books’ success.

I wrote a long blog last year about Patrick O’Brian, whose series of novels about the Navy in Napoleonic times is as much a study of a long friendship as it is an extended adventure. O’Brian sustained a high quality until the last few books in the series, when age may have dulled his sensibilities. These books deserve to survive; he is not a great writer, but he is a very good one, and his achievement of charting the course of a friendship, two careers and two marriages against a dramatic historical background over the course of more than twenty books is unparalleled.

Two other historical novels deserve a mention: J G Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur, set at the time of the Indian Mutiny, and Paul Scott’s Staying On, about the end of the British Empire in India. Scott is better known for his four-book series The Jewel in the Crown, which was made into an award-winning television series, but Staying On addresses similar themes with the same subtlety and greater economy. I found Staying On a more evocative book and its characters more sympathetic.

Two other historical novels deserve a mention: J G Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur, set at the time of the Indian Mutiny, and Paul Scott’s Staying On, about the end of the British Empire in India. Scott is better known for his four-book series The Jewel in the Crown, which was made into an award-winning television series, but Staying On addresses similar themes with the same subtlety and greater economy. I found Staying On a more evocative book and its characters more sympathetic.

Krishnapur won the Booker prize and should have won the Booker of Bookers (it was shortlisted but lost out to Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children). The siege and a last-minute rescue give a structure to the story, but its main qualities are in the characterisation, not just of individuals but of the community in which they live. Farrell writes with an eerie detachment, implying no judgement but leaving us to draw our own conclusions. It is a great book; but sadly Farrell died young and never wrote another half as good.

Krishnapur won the Booker prize and should have won the Booker of Bookers (it was shortlisted but lost out to Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children). The siege and a last-minute rescue give a structure to the story, but its main qualities are in the characterisation, not just of individuals but of the community in which they live. Farrell writes with an eerie detachment, implying no judgement but leaving us to draw our own conclusions. It is a great book; but sadly Farrell died young and never wrote another half as good.

——————–

The great, the good and the favourites (1)

3 May 2018

In a recent conversation David more or less challenged John and me to reply to his blog of 19 April. “What distinguishes a great author from a good one?” John’s had his go; now it’s my turn. But, really, it’s an impossible question. Such judgements are subjective, and so are the criteria used. The modern way is to ascribe greatness far too readily. Was David Beckham a great footballer? Or Alan Rickman a great actor? Is The Wire great television drama? Or were they all just very, very good?

But if we consider the combined judgements of literary historians and critics alongside the reading preferences of the general public there are three English authors who stand out from the rest: Austen, Dickens and Eliot. They are the galacticos, the true greats. None of them is perfect. Austen’s range is limited. Dickens has a streak of gross sentimentality. Eliot’s “constipated” prose style (© an Amazon reviewer) is a bit forbidding. But their strengths far outweigh the deficiencies.

Nowhere is this more true than in Dickens. An Oxford friend of mine thinks Bleak House the greatest novel ever written in English. I wouldn’t go that far, but it is probably Dickens’ best (though Our Mutual Friend and Great Expectations might compete for that title). At school one of the English masters quoted with approval a criticism by E M Forster, who said that Dickens’ characters were two-dimensional. This is mostly fair (though with exceptions), but does it matter? Deep characterisation is one quality of a novel, but to my mind it is neither sufficient nor necessary. The gallery of caricatures who populate Dickens’ novels are intentionally grotesque. Dickens was a satirist, and this was a way he had of making a point. And his characters may lack depth, but they are vivid and memorable.

Dickens wrote 15 novels. Not all are equally good, or to modern taste. The Old Curiosity Shop is almost unreadable nowadays for its sustained over-the-top sentimentality. The Pickwick Papers and Martin Chuzzlewit are ramshackle structures, a lot less than the sum of their parts. David Copperfield, partly autobiographical, is just dull, lacking most of Dickens’ usual satire and humour. I remember that Mum first introduced me to Dickens through Copperfield: it was a mistake, and not until university did I discover that Dickens, among many other qualities, is often very funny. But we can scarcely judge an author by their worst work. Even the venerated George Eliot produced Romola, a historical novel set in Renaissance Italy, which has baffled or bored many readers. Only Austen’s six novels achieve sustained excellence. I agree with David in liking Emma the best, but they are all of the highest quality and eminently readable today.

There is a second rank of authors not far behind the three galacticos: the Brontë sisters, Gaskell, Trollope, Hardy, Conrad, possibly Thackeray, no doubt others who don’t spring readily to mind. I have never myself been able to come to terms with Conrad, whom I have always found too turgid, but on David’s recommendation perhaps I should try again. I remember admiring Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge when I read it many years ago, but I had no patience with either Tess or Jude or with the studied rusticism of Under The Greenwood Tree. I enjoy Trollope, who is never less than competent and readable, without too many pretentions to style; but he tends to tell us, rather than just show us, what his characters are thinking. Trollope’s best may be those where there is an element of tragedy alongside the conventional happy ending: The Last Chronicle of Barset, He Knew He Was Right, The Way We Live Now (recently the subject of a so-so TV adaptation). The first two of these are in places quite an uncomfortable read, which is not what one usually associates with Trollope.

Gaskell is very good, and possibly underestimated on the strength of her best known novel, Cranford. She also wrote Wives and Daughters, and North and South, longer and more substantial novels which make a serious attempt to address contemporary issues within the conventional form. I think she also suffers a bit through an implicit comparison with Eliot who appears on the face of it to be doing the same kind of thing, just a bit better. Which I do not think does either of them justice.

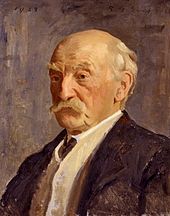

Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë, painted by Branwell Brontë (who also painted himself out – you can just see his ghostly figure)

The Brontë sisters are a special case. If we think of them as a group rather than three individuals they probably belong alongside the galacticos. I should guess that Wuthering Heights and, especially, Jane Eyre are among the most widely read and influential of all the English classical canon. Though “classical” is scarcely the word: these are works of high romanticism, influential on generations of authors but scarcely matched in all of English literature.

I agree, though, with David’s distinction between great authors and great books. Wuthering Heights is a great novel, but Emily Brontë wrote no others; on the strength of this one book can we describe her as a great author? Charlotte wrote three other novels besides Jane Eyre, and Anne wrote one other besides The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, without achieving the same heights as in their greatest works.

The same can be said of Thackeray. After our conversation with David, John reminded me about Vanity Fair, another very great novel, and possibly the first with a true anti-hero(ine) as its central figure. But Thackeray wrote several other novels which are now virtually forgotten. Oddly his next best known work may now be a children’s story, The Rose and the Ring, which is republished from time to time. It is an intentional satire filled with fanciful names, puns and undermining of fairy-tale tropes, calculated to appeal to adults and children alike. As a boy I loved it.

The same can be said of Thackeray. After our conversation with David, John reminded me about Vanity Fair, another very great novel, and possibly the first with a true anti-hero(ine) as its central figure. But Thackeray wrote several other novels which are now virtually forgotten. Oddly his next best known work may now be a children’s story, The Rose and the Ring, which is republished from time to time. It is an intentional satire filled with fanciful names, puns and undermining of fairy-tale tropes, calculated to appeal to adults and children alike. As a boy I loved it.

Conrad died in 1924 and Hardy in 1928. I haven’t been able to think of any authors since then whom I would confidently place on a par with them. Perhaps true consistent greatness can only be identified with the passage of time. I can think of half a dozen or so individual novels which might qualify as great, but it’s difficult to be sure how much of this is my personal preference, rather than a broader-based assessment.

David lists several books he has enjoyed and would recommend, but I doubt whether any of them will be regarded in the long term as great books, except possibly Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, which is rightly regarded as a children’s classic. Oddly Garner now almost disowns the book, feeling that its protagonists Colin and Susan are characterless and its structure unbalanced. He is right on both counts, but that does not make The Weirdstone any less of a classic. I agree with David: the book has a haunting, lyrical quality and includes a number of scenes which, even after fifty years I can still call vividly to mind.

David lists several books he has enjoyed and would recommend, but I doubt whether any of them will be regarded in the long term as great books, except possibly Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, which is rightly regarded as a children’s classic. Oddly Garner now almost disowns the book, feeling that its protagonists Colin and Susan are characterless and its structure unbalanced. He is right on both counts, but that does not make The Weirdstone any less of a classic. I agree with David: the book has a haunting, lyrical quality and includes a number of scenes which, even after fifty years I can still call vividly to mind.

So, to answer David’s original question. One quality shared by all these authors, great and (by my narrow definition) nearly great, is that they have survived the test of time. I haven’t checked, but I am pretty sure that all their books remain in print today, and find a readership that extends beyond the academic and critical world. Beyond that, they all have, to varying degrees, a range of durable qualities: memorable stories and characters, psychological insight, style and structure, depth and purpose.

As for my favourites and recommendations in modern fiction… well, they need a separate blog.